The new programme of action for LDCs for the next decade will kick off in 2022 against an extremely challenging backdrop. COVID-19 has caused an unprecedented global economic crisis, with severe impacts on international trade and investment flows. The global economy contracted by 3.3 per cent in 2020, according to International Monetary Fund (IMF) data, with the impact felt even more severely in developed economies, where growth shrank by 4.7 per cent. The ensuing worldwide economic fallout significantly affected the economic performance of Commonwealth countries. The Commonwealth’s 54 member countries suffered a collective loss of US$1.15 trillion to their GDP in 2020 compared with the pre-pandemic estimate (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2021). As many as 45 Commonwealth countries underwent recessions in 2020, including nine LDC members. Among the Commonwealth LDCs, only Bangladesh, The Gambia, Malawi, Tanzania and Tuvalu registered positive growth (ibid.).

While the cumulative numbers of cases and deaths as a result of COVID-19 have generally been relatively low in Commonwealth LDCs compared with many other developing and developed countries (Table 12), the wider economic and socio-economic impacts of the pandemic have been especially severe in LDCs, given their relative lack of resilience and limited resources to react with fiscal rescue packages and social protection responses (Box 3). The pandemic has rolled back some of the progress LDCs have made in recent decades and threatens to widen the already sizeable income gap between them and other developing countries. Slow progress in vaccinating their populations against the virus (see the final column of Table 12), even in comparison with many other non-Commonwealth LDCs and especially compared with the average for other developing countries, portends a more protracted pandemic and may delay broader economic recovery in these countries.

|

Box 3: The startling socio-economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in LDCs While case numbers and deaths from COVID-19 have generally been lower in LDCs than in other country groups, these countries have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic’s adverse socio-economic effects. This owes largely to their lack of resilience and capacity to respond to the ensuing social and economic crises. In many instances, the pandemic’s impacts have been amplified because of the absence of robust health and social protection systems in LDCs (UNESCAP, 2021). These already overburdened systems have faced increasing pressure as a result of the large numbers of migrant workers returning after losing their jobs in other countries because of the COVID-19 crisis (UN-OHRLLS, 2020). The economic fallout from COVID-19 threatens to reverse hard-won gains in alleviating poverty in LDCs over the course of successive programmes of action. One estimate suggests an additional 35 million people in LDCs are living in extreme poverty (on less than US$1.90 per day) as a result of the pandemic. As much as 35 per cent of the combined populations of LDCs are estimated to be living below the extreme poverty line as of 2021. Rising poverty levels in LDCs are exacerbated by increasing food security risks on the back of the disruptions generated by COVID-19. The pandemic has curtailed some agricultural activities, disrupted food supply chains and led to rising prices for stable foods such as grains, poultry and vegetables (UNESCAP, 2021; UN-OHRLLS, 2021). The severe economic effects of COVID-19 have also contributed to rising unemployment in almost all Commonwealth LDCs (see Section 5.4.4). Women have been among the most affected as they tend to constitute a large share of the workers employed in services sectors such as retail and tourism that have been severely affected by lockdowns and other restrictions imposed to combat COVID-19. Women are also often employed in the sort of labour-intensive, low-skilled activities that have been most vulnerable to job losses as a result of the pandemic (see Box 4). Similarly, COVID-related lockdowns and restrictions have had disproportionate impacts on workers employed in the informal economy, many of whom have limited cash reserves, lack access to digital technologies and are unable to engage in teleworking, and often have difficulty accessing social protection systems (UN-OHRLLS, 2021). The longer-term developmental impacts of the pandemic in LDCs may be felt only in years to come. This is especially concerning in relation to education. With school closures and diminishing household incomes and livelihoods, many learners in LDCs – and especially girls – have had their education disrupted. One multi-country estimate by Azevedo et al. (2020) suggests 0.6 years of schooling have been lost as a result of the pandemic. Many learners in LDCs have been disproportionately affected since they tend to have limited access to technologies supporting remote learning and digital education, which has been necessary during pandemic-induced lockdowns (UN-OHRLLS, 2020; CDP, 2021). Longer-term health outcomes not directly related to the pandemic itself may also deteriorate in LDCs. The pandemic has severely disrupted the provision of health services in these countries, placing even greater pressure on already overburdened and poorly resourced healthcare systems. This risks reversing the progress LDCs have made in lowering mortality rates, alleviating malnutrition and combating diseases (CDP, 2021). These challenges highlight just how urgently resources need to be scaled up to assist LDCs to address the socio-economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Failure to do so would risk undermining the significant developmental progress made during the IPoA and the successive programmes of action that preceded it. |

Perhaps most concerning is the reality that the COVID-19 pandemic threatens to reverse the economic transformation gains Commonwealth LDCs have achieved. Employment losses may push even larger shares of workers towards lower-productivity jobs or into informal sector work. This could result in a sustained shift in employment and other resources towards agriculture, the informal sector and/or less-skilled occupations. Moreover, women and youths, less-skilled workers and those living in rural areas are likely to be disproportionately affected, with adverse impacts on progress towards inclusive economic transformation.

This chapter examines the broad impacts of COVID-19 on growth, employment and trade in Commonwealth LDCs by comparing pre-pandemic trends with available data for 2020. It also assesses the pandemic’s impacts on the availability of financing and investment for productive development in these countries. The considerable economic and socio-economic consequences of COVID-19 this chapter highlights have exacerbated many of the challenges outlined in Chapters 2, 3 and 4. These setbacks will severely jeopardise the ability of Commonwealth LDCs to achieve the ambitious goals set out in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda.

Table 12: COVID-19 cumulative cases, deaths and vaccinations (as published on 9 December 2021)

|

Country |

Total population (in 2020) |

Cases - cumulative total |

Cases - cumulative total per 100,000 population |

Deaths - cumulative total |

Deaths - cumulative total per 100,000 population |

Persons fully vaccinated per 100 people |

|

Bangladesh |

164,689,383 |

1,578,011 |

958 |

28,010 |

17 |

22 |

|

The Gambia |

2,416,664 |

9,998 |

414 |

342 |

14 |

9 |

|

Kiribati |

119,446 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

19 |

|

Lesotho |

2,142,252 |

21,838 |

1,019 |

663 |

31 |

27 |

|

Malawi |

19,129,955 |

62,015 |

324 |

2,307 |

12 |

3 |

|

Mozambique |

31,255,435 |

152,120 |

487 |

1,941 |

6 |

13 |

|

Rwanda |

12,952,209 |

100,449 |

776 |

1,343 |

10 |

23 |

|

Sierra Leone |

7,976,985 |

6,405 |

80 |

121 |

2 |

5 |

|

Solomon Islands |

686,878 |

20 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

Tanzania |

59,734,213 |

26,309 |

44 |

734 |

1 |

2 |

|

Tuvalu |

11,792 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

Uganda |

45,741,000 |

127,822 |

279 |

3,261 |

7 |

2 |

|

Vanuatu |

307,150 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

|

Zambia |

18,383,956 |

210,374 |

1,144 |

3,668 |

20 |

3 |

|

CW LDC total |

- |

2,295,366 |

- |

42,390 |

- |

- |

|

CW LDC avg. |

- |

163,955 |

395 |

3,028 |

9 |

14 |

|

Non-CW LDC avg. |

- |

81,961 |

491 |

1,976 |

9 |

13 |

|

Developing country avg. (excl. LDCs) |

- |

1,352,927 |

5,103 |

29,808 |

87 |

42 |

Note: The figures in the table are based on data published on 9 December 2021.

Source: World Health Organization Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard; World Bank World Development Indicators (population data)

5.1 Impacts on output and value added

Amid the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the LDC group as a whole registered their worst economic growth performance in three decades (UNCTAD, 2021c). Only eight out of 46 LDCs recorded positive growth rates in 2020 (ECOSOC, 2021a). On average, GDP growth declined by 1.3 per cent across the LDC group, a sharp contraction compared with the projected growth rate of 5.1 per cent at the beginning of 2020 (UN-OHRLLS, 2021).

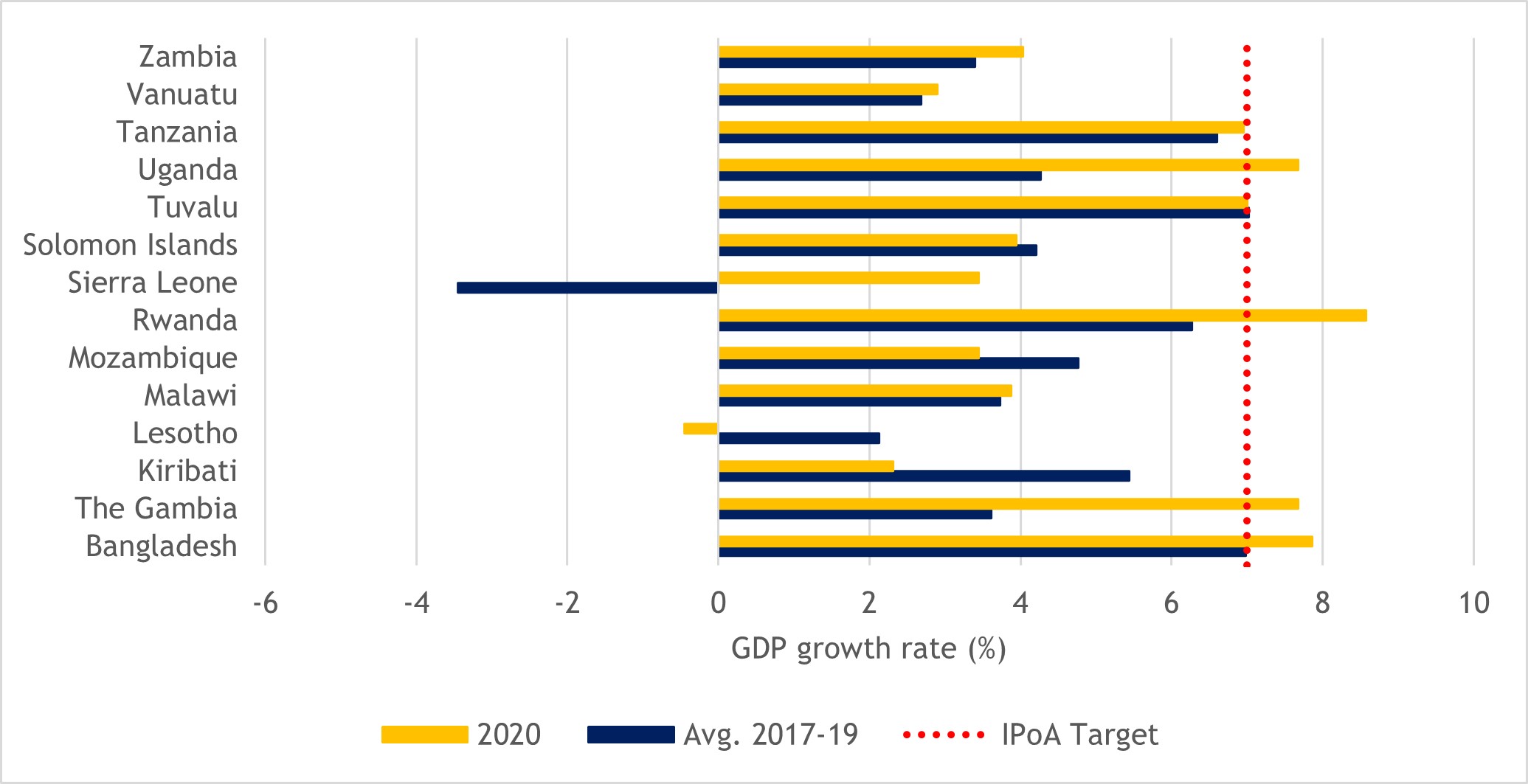

Despite the negative overall picture for LDCs, GDP growth rates were generally robust in Commonwealth LDCs even as the pandemic took hold. Their GDP grew faster, on average, in 2020 than that of non-Commonwealth LDCs as well as other developing countries. Only four Commonwealth LDCs – Kiribati, Lesotho, Mozambique and Solomon Islands – recorded lower GDP growth in 2020 compared with the annual average for the pre-pandemic period (2017-2019) (Figure 33). GDP in Bangladesh, The Gambia, Malawi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Tanzania, Vanuatu and Zambia grew faster in 2020 compared with pre-pandemic averages. Moreover, growth rates were either at or above the IPoA target in Bangladesh, The Gambia, Tanzania, Tuvalu and Uganda in 2020.

Figure 33: GDP growth rates in Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020 (%)

In eight of the 14 Commonwealth LDCs, increases in GDP per capita matched the relatively robust growth performance in 2020 (Table 13). In contrast, Lesotho, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Zambia all saw GDP per capita decline; the reductions in Lesotho and Zambia were especially large. Even so, while average GDP per capita for the Commonwealth LDC group declined by 1.6 percentage points, the equivalent decline was much larger, on average, across non-Commonwealth LDCs (18.6 percentage points).

Table 13: GDP per capita in Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020 (current US$)

|

|

Avg. 2017-2019 |

2020 |

Percentage point change 2017-2019 vs. 2020 |

|

Bangladesh |

1,706 |

1,969 |

15.4 |

|

The Gambia |

730 |

787 |

7.8 |

|

Kiribati |

1,665 |

1,671 |

0.4 |

|

Lesotho |

1,136 |

861 |

-24.2 |

|

Malawi |

539 |

625 |

16.1 |

|

Mozambique |

489 |

449 |

-8.3 |

|

Rwanda |

792 |

798 |

0.7 |

|

Sierra Leone |

520 |

485 |

-6.9 |

|

Solomon Islands |

2,363 |

2,258 |

-4.4 |

|

Tanzania |

1,045 |

1,076 |

3.1 |

|

Tuvalu |

3,777 |

4,143 |

9.7 |

|

Uganda |

771 |

817 |

6.0 |

|

Vanuatu |

3,103 |

2,783 |

-10.3 |

|

Zambia |

1,452 |

1,051 |

-27.6 |

|

Non-CW LDC avg. |

9,919 |

8,075 |

-18.6 |

|

Developing country avg. (excl. LDCs) |

1,227 |

1,205 |

-1.8 |

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using World Bank World Development Indicators data)

The analysis presented above suggests GDP was relatively robust in Commonwealth LDCs in 2020, despite the economic turmoil COVID-19 generated. However, it masks important differences in COVID-related impacts across sectors. The pandemic has severely affected some sectors that are traditionally of critical importance to LDC economies. Moreover, sectors such as non-food manufacturing, accommodation, travel, transport and wholesale and retail trade – where there tends to be an over-representation of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and women employees (see Box 4) – have been among the most affected (UN-OHRLLS, 2021).

|

Box 4: Gender-related impacts of COVID-19 and implications for women’s economic empowerment in Commonwealth LDCs Women and women-owned businesses in Commonwealth LDCs have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because they are over-represented in sectors such as tourism, transport and travel, retail, food services, accommodation, entertainment and recreation, and manufacturing that are more vulnerable to COVID-related economic shocks (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2021). The impacts on the garment sector, for example, have been severe. Garment production has been hampered by delays in accessing imported inputs as a result of supply chain blockages as well as COVID-related worker shortages. These supply-side issues have been compounded by sharp declines in consumer demand in key markets owing to lockdowns and mandatory closures of clothing retail stores. This has resulted in large-scale cancellation or postponement of production orders and, in certain instances, delayed payments for completed orders. These impacts have major implications for women since they constitute the majority of garment manufacturing workers in Commonwealth LDCs such as Bangladesh, Lesotho and Tanzania. Many of these workers, who already had low wages, poor job security and limited access to social safety nets before the pandemic, have seen their incomes fall, faced reduced working hours and, in some instances, lost their jobs. In Bangladesh, for example, more than 1 million garment workers lost their jobs or were furloughed before the end of March 2020 (Anner, 2020). A large survey by the Worker Rights Consortium in 2020, covering 396 garment sector workers (70 per cent of whom were women) in 158 factories spread across nine countries (including Bangladesh and Lesotho), revealed that 38 per cent of workers had either lost their jobs or had them temporarily suspended as a result of the pandemic. Several services sectors employing large shares of women in Commonwealth LDCs have been hit hard by the limitations on in-person interaction imposed to combat COVID-19. Among these, the tourism and travel sectors have fared especially badly, because of the extensive global travel restrictions and resulting contraction of the global tourist economy. Across all facets of life, many women in Commonwealth LDCs have been ill-equipped to deal with the changes the pandemic has necessitated. The accelerated reliance on digital technologies in a variety of areas, from healthcare and education to work, commerce and trade, has exposed deep-set gender-related digital divides. Differences between women and men in mobile phone access and usage, digital connectivity and participation in the digital economy mean many women were disadvantaged as the pace of digitalisation intensified with the emergence of COVID-19. The expansion of the global digital economy, alongside the growing prominence of services in international trade, presents new economic opportunities for women in LDCs. However, these opportunities may remain unrealised if the gender digital divide and other factors, such as a lack of access for women to financial services and formal employment, are not addressed. The programme of action for the next decade needs to direct renewed attention towards addressing these constraints as part of a comprehensive and inclusive approach to women’s economic empowerment. |

In the tourism sector, for example, pandemic-induced travel restrictions as well as sharp declines in incomes in traditional tourist markets in developed countries halted most of the tourist activity in Commonwealth LDCs. In key export-oriented manufacturing sectors, such as textiles and readymade garments, factory closures, labour and input shortages, falling FDI, disruptions to regional and global value chains, and slumping export demand massively affected production in Bangladesh, Lesotho, Tanzania and other garment-producing Commonwealth LDCs. Overall, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) estimates that manufacturing growth slowed to 1.2 per cent across the entire LDC group in 2020, a significant drop from the 8.1 per cent growth in 2019 (ECOSOC, 2021a).

Annual growth in manufacturing value added contracted in 2020 compared with pre-pandemic averages in all eight Commonwealth LDCs with available data (Table 14). The contraction was especially large in Lesotho, which saw a fall by 22 percentage points. Growth in value added in the broader industry sector was similarly affected, contracting in all but one (Sierra Leone) of the nine Commonwealth LDCs in Table 14. Likewise, annual growth in services value added contracted in all nine of these countries, with the services sectors in Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Zambia the most affected.

The impact of COVID-19 on agricultural, forestry and fishing value added was more varied across the Commonwealth LDCs included in Table 14. Lesotho and Zambia registered strong growth in 2020 relative to their pre-pandemic averages, and there was modest growth in Uganda. However, this contrasted with contractions ranging from 0.7 to 4.4 percentage points in the remaining six Commonwealth LDCs.

Table 14: Changes in annual growth of sectoral value added in agriculture, forestry and fishing, manufacturing, industry and services, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020 (percentage point change)

|

Country |

Agriculture, forestry and fishing |

Manufacturing |

Industry |

Services |

|

Bangladesh |

-0.7 |

-10.4 |

-3.2 |

|

|

Lesotho |

34.6 |

-22.0 |

-10.4 |

-9.9 |

|

Malawi |

-0.7 |

-5.7 |

-4.5 |

-5.2 |

|

Mozambique |

-0.3 |

-3.2 |

-10.6 |

-4.8 |

|

Rwanda |

-4.4 |

-8.4 |

-13.2 |

-13.4 |

|

Sierra Leone |

-1.8 |

-4.3 |

0.4 |

-18.3 |

|

Tanzania |

-1.2 |

-4.5 |

-7.7 |

-3.5 |

|

Uganda |

0.7 |

-4.0 |

-5.6 |

-2.1 |

|

Zambia |

18.4 |

-5.1 |

-1.6 |

-10.3 |

|

Non-CW LDC avg. |

-1.7 |

-4.7 |

-6.1 |

-5.8 |

|

Developing country avg. (excl. LDCs) |

-2.1 |

-8.1 |

-4.8 |

-9.7 |

Notes: No data available on growth in manufacturing value added for Bangladesh in 2020. No data available for all sectors in The Gambia (2020), Kiribati (2019 and 2020), Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu (all relevant years).

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using World Bank World Development Indicators data)

5.2 Trade impacts

While the health impacts of COVID-19 have been relatively muted in many LDCs compared with their developing country counterparts, the direct and indirect economic consequences have been substantial. Compared with a modest drop in the GDP of LDCs, the decline in exports was considerably higher. In 2020, the combined GDP of all 47 LDCs was almost at the level observed in 2019,[1] and that for all 14 Commonwealth LDCs was US$9 billion higher than in the previous year. Apart from Lesotho, the economies of 13 Commonwealth LDCs grew marginally in 2020 (see Section 5.1). However, the weakening relationship between GDP and trade (discussed in Chapter 3) was reflected in lower exports from all countries.

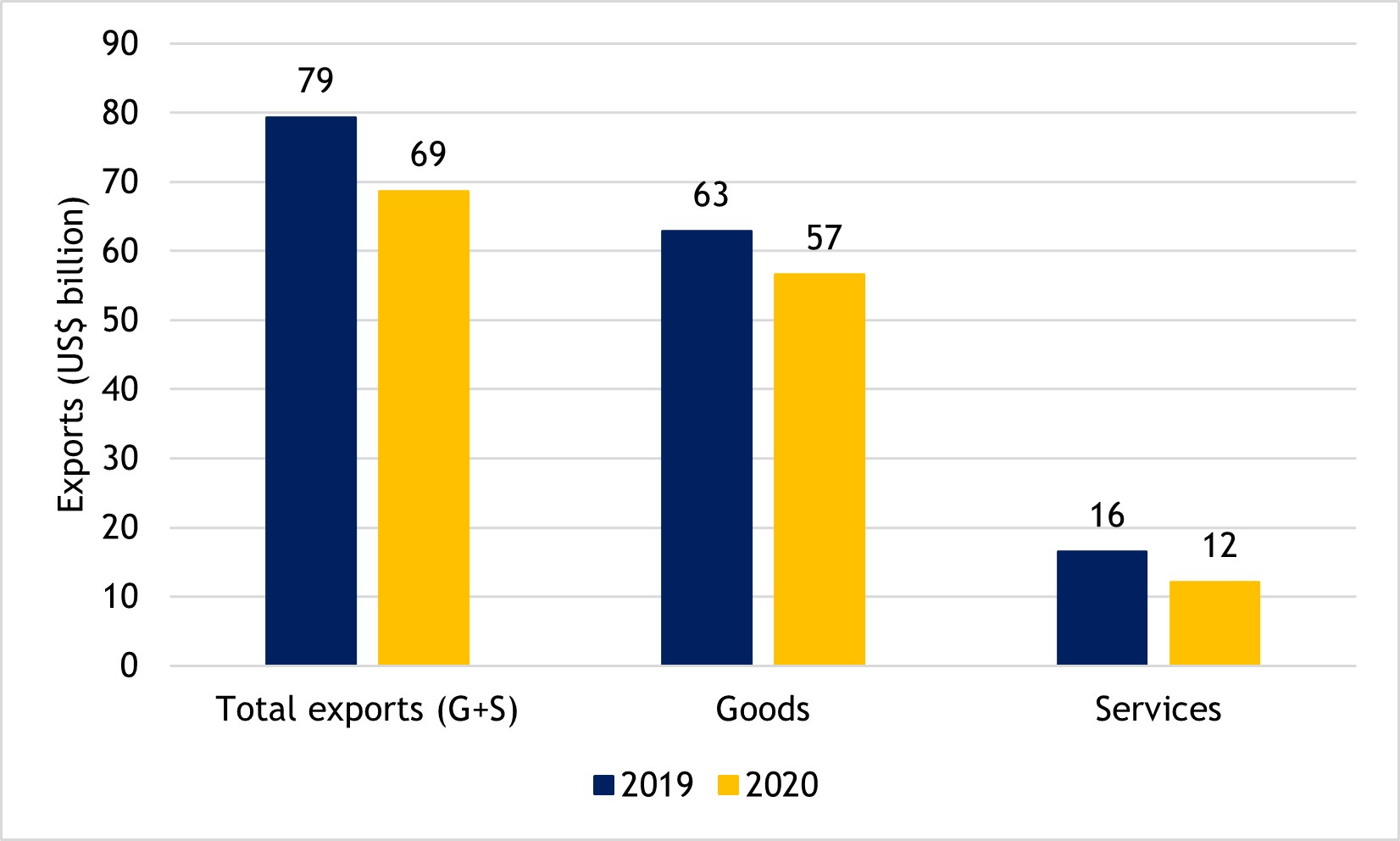

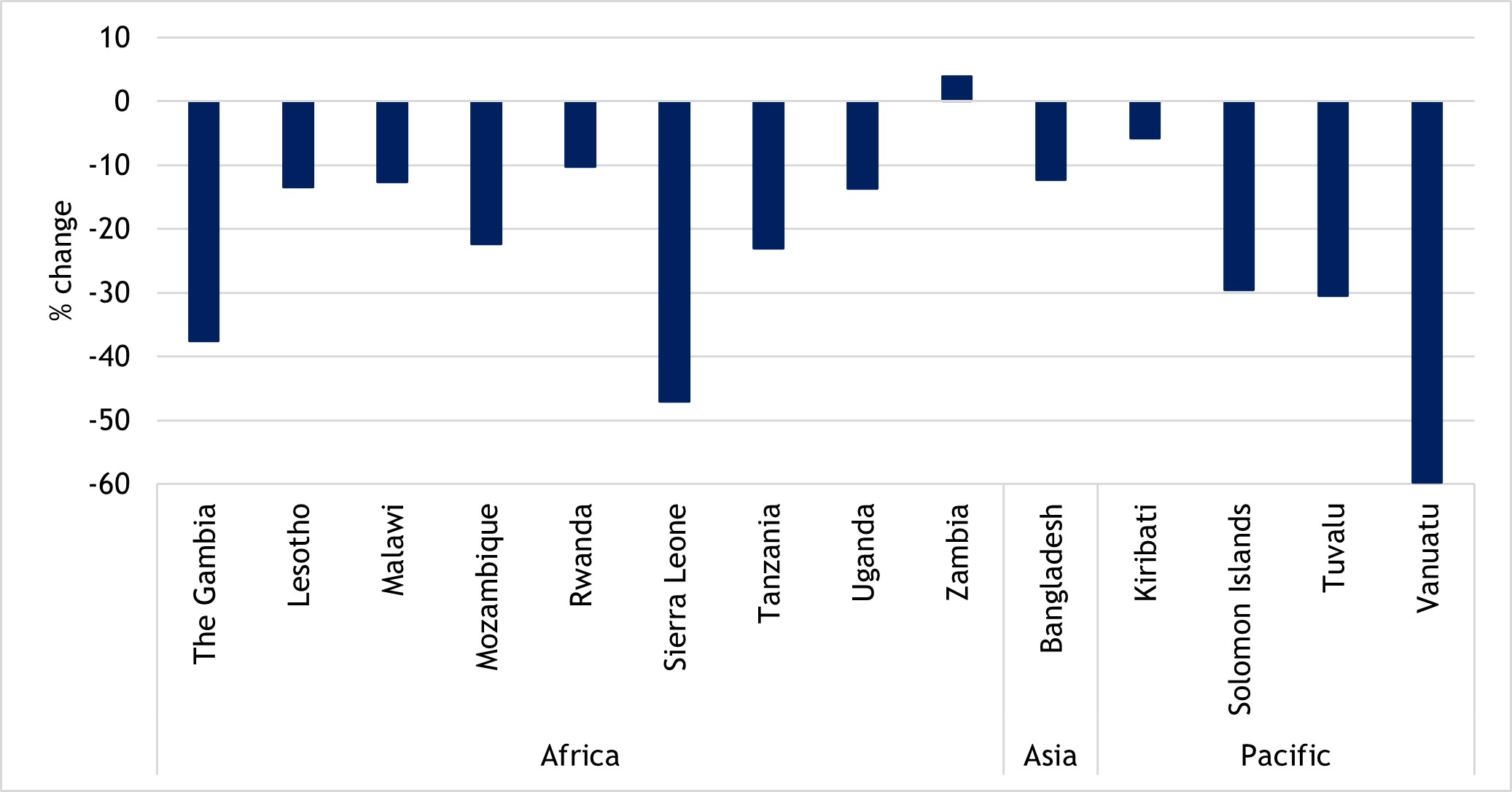

In 2020, the combined value of Commonwealth LDCs’ global exports dropped by US$10 billion, and this effect transmitted through both goods and services exports, with the latter relatively more affected (Figure 34). Zambia aside, exports from the other 13 LDCs were lower than in 2019 (Figure 35).[2] In value terms, global exports by Commonwealth LDCs reverted to levels last observed in 2016.

Figure 34: Commonwealth LDCs’ global exports during the pandemic, 2019 vs. 2020 (US$ billion)

The contagion had a relatively larger impact on the four Pacific members, whose exports shrank by 40 per cent on average (Figure 35). Among these LDCs, Vanuatu experienced the largest decline, at about 60 per cent. A higher share of services in the total exports of these countries, ranging from a quarter in Kiribati to more than 90 per cent for Tuvalu and Vanuatu, made them extremely susceptible to COVID-19 shocks, which had a disproportionate effect on contact-intensive services such as hospitality, travel and tourism.

Figure 35: Changes in Commonwealth LDCs’ exports between 2019 and 2020, by country and region (%)

The exports of Commonwealth African LDCs dropped by 14 per cent in just one year. The sharp rebound in commodities prices and exports from most African economies in the second half of 2020 meant they fared relatively better than the Pacific LDCs. The merchandise exports of Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia were higher in 2020 compared with 2019.

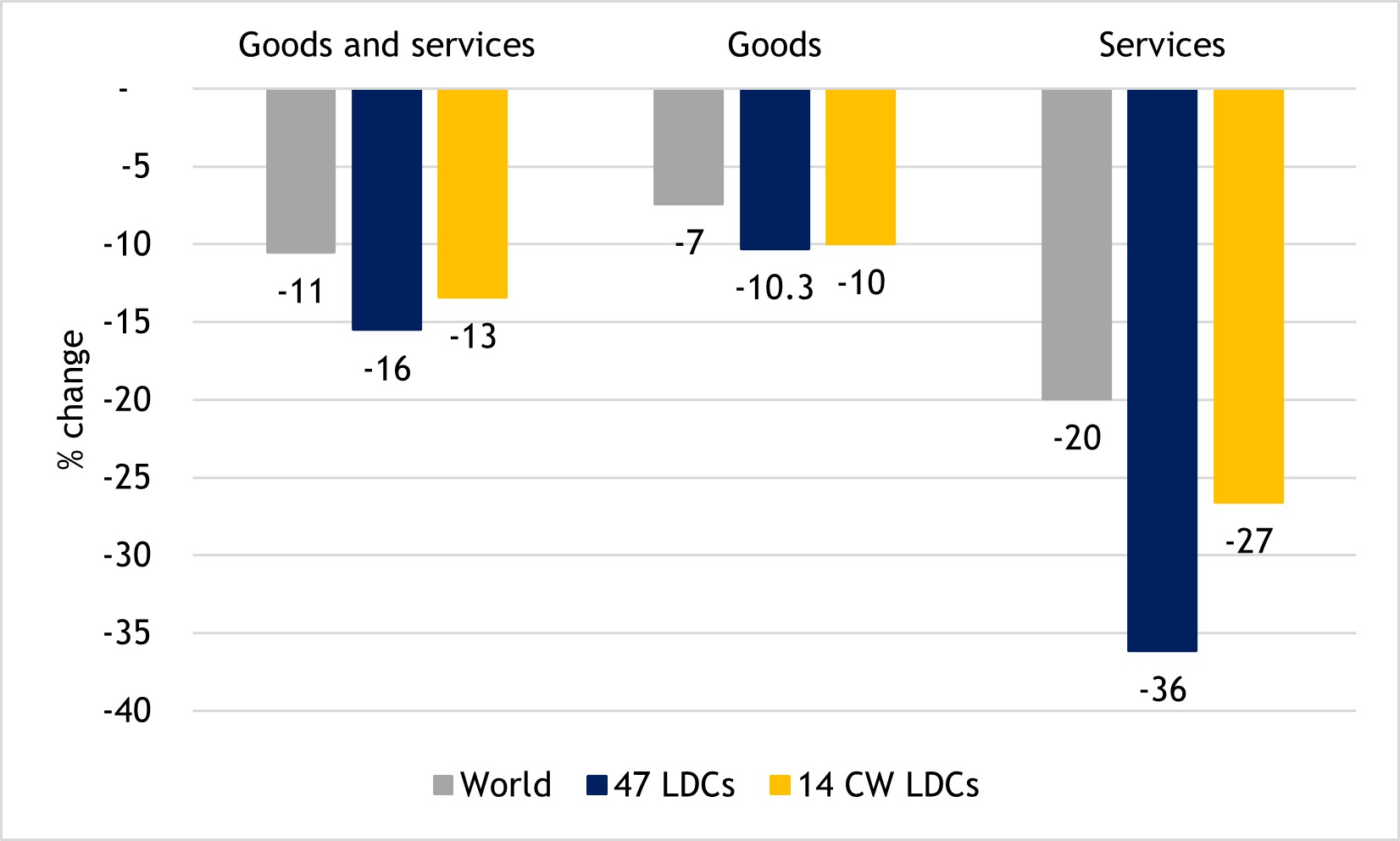

5.2.1 Sectoral implications of the pandemic for Commonwealth LDC trade

The pandemic exacerbated pre-existing vulnerabilities in LDCs. As a result, the decline in their exports was far worse than that for the rest of the world, with both goods[3] and services exports affected (Figure 36). However, the impacts varied across sectors, with services exports generally most affected. In 2020, Commonwealth LDCs’ global services exports amounted to US$12 billion, a drop of 27 per cent from 2019. The decline in the services exports of non-Commonwealth LDCs was even higher (Figure 36). The impact on tourism and hospitality services, which constitute a major sector of the economy in the four Commonwealth LDCs in the Pacific (Kiribati, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu), has been significant.

The merchandise exports of Commonwealth LDCs fell by 10 per cent and their intra-Commonwealth exports by 13 per cent. The merchandise imports of these countries also shrank, but to a lesser extent, with reductions of 9 and 11 per cent in global and intra-Commonwealth imports, respectively.

Figure 36: Differential effects of the pandemic on goods and services exports, 2020 vs. 2019 (% change)

The pandemic has reversed the long-term trend of growth in services exports by LDCs. Between 2011 and 2019, the value of their services exports almost doubled, from US$9 billion to more than $16 billion, an increase of close to 85 per cent. All Commonwealth regions benefited from this growth but to varying degrees. Except for Lesotho and Sierra Leone, services exports from all other Commonwealth African LDCs expanded, raising the share of services in their total exports by 5 percentage points (Table A4). The pandemic has effectively halved these gains and the impacts have been relatively more severe on the Pacific and African LDCs.

5.2.2 Effect on the IPoA trade targets and graduation prospects for Commonwealth LDCs

The COVID-19 pandemic pushed world trade back to 2011 levels. The combined export share of all 47 LDCs, which increased slightly during the global trade boom between 2018 and 2019, also dropped back in 2020, to around 1 per cent. Commonwealth LDCs fared better in this period. However, as discussed in Chapter 3, the large growth in exports from Bangladesh skews this overall picture.

LDCs were already set to miss the IPoA trade targets before the emergence of COVID-19, but the pandemic has exacerbated existing challenges and offset some of the progress made during this period. The share of Commonwealth LDCs in global exports was just 1.27 times greater in 2019 compared with 2011, thus falling well short of the IPoA target (reflected in SDG 17.11) of doubling the overall LDC export share. The larger decline in LDC exports relative to the equivalent drop in world trade in 2020 has offset some of these modest gains. When the pandemic-induced collapse in trade is factored in, Commonwealth LDCs’ trade increased only marginally from the levels witnessed in 2011 at the start of the IPoA.

This large decline in LDC exports poses a significant threat to sustainable graduation pathways. The wait for large-scale vaccination, and the relative return to economic normality it portends, may derail the preparations of Commonwealth LDCs on the cusp of graduating (Bangladesh and Solomon Islands) and impede progress for those to be considered for graduation in the near future. Despite these challenges, Vanuatu graduated in December 2020, but Bangladesh has already extended its transition period by two years and is now set to exit the LDC group in 2026. LDCs have also made a request at the WTO for LDC-specific support measures, including special and differential treatment (S&DT) and other flexibilities, to be extended as part of a longer 12-year transition period for graduating countries (see Chapter 6).

5.3 Impacts on FDI inflows to Commonwealth LDCs

COVID-19 has disrupted global FDI flows primarily through delays to the implementation of existing investment projects, the deferral of decisions on new investments, reductions in reinvested earnings and declining equity capital flows. Global FDI flows fell by 42 per cent in 2020 (UNCTAD, 2021a). As a result, FDI inflows to most Commonwealth LDCs were badly affected. The overall value of these inflows declined in 2020 relative to pre-pandemic averages (for 2017-2019) in all but four of the 14 Commonwealth LDCs (Table 15). In relative terms, these declines were especially severe for Malawi, Rwanda, Solomon Islands and Zambia. Only The Gambia, Sierra Leone and Tanzania managed to attract more FDI in 2020 compared with their pre-pandemic averages, with inflows rising by US$111 million (or 46 per cent) to Sierra Leone and by 20 per cent – off a small base – in The Gambia.

Table 15: Changes in the value of overall FDI inflows to Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020

|

|

Value of inflows (US$ million) |

|

|

|

Avg. 2017-2019 |

2020 |

% change 2017-2019 vs. 2020 |

|

|

Sierra Leone |

238 |

349 |

46.4 |

|

The Gambia |

38 |

46 |

20.0 |

|

Tanzania |

967 |

1013 |

4.8 |

|

Kiribati |

-0.3 |

0 |

- |

|

Mozambique |

2403 |

2337 |

-2.7 |

|

Bangladesh |

2880 |

2564 |

-11.0 |

|

Lesotho |

123 |

102 |

-17.2 |

|

Vanuatu |

37 |

30 |

-20.0 |

|

Uganda |

1039 |

823 |

-20.8 |

|

Rwanda |

364 |

135 |

-63.0 |

|

Zambia |

688 |

234 |

-66.0 |

|

Tuvalu |

0.3 |

0 |

-66.6 |

|

Solomon Islands |

33 |

9 |

-72.7 |

|

Malawi |

624 |

98 |

-84.3 |

|

ALL LDCs |

22,422 |

23,610 |

5.3 |

|

WORLD |

1,538,091 |

998,891 |

-35.1 |

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using UNCTAD World Investment Report 2021 data)

Across all types of FDI, greenfield investments have been among the most affected by the economic consequences of COVID-19. This has dealt a major blow to the development of productive capacity and new jobs in developing countries, and LDCs in particular. The world’s LDCs collectively experienced a sharp drop in both the number and the value of greenfield project announcements in 2020. These declined by 51 per cent in 2020 compared with 2019, reaching the lowest level for 13 years stretching back to the global financial crisis (UNESCAP, 2021). As many as 17 of the 46 LDCs did not attract any greenfield FDI projects in 2020 (UNCTAD, 2021c).

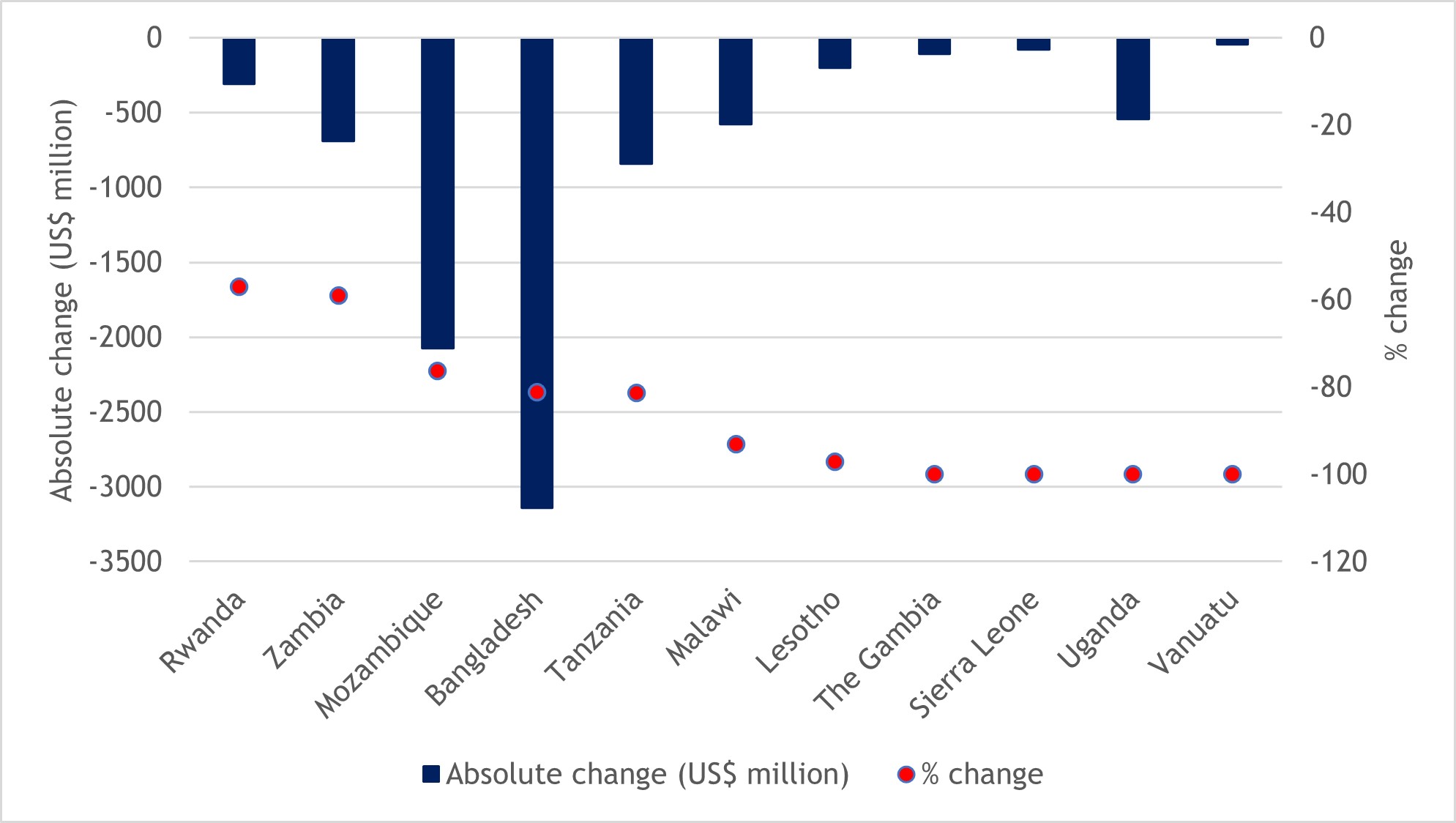

All 11 Commonwealth LDCs in Figure 37 experienced a decline in the value of announced greenfield FDI inflows in 2020 compared with their pre-pandemic averages. The decline was most pronounced in absolute terms in Bangladesh, where the combined value of capital investments fell by more than US$3.1 billion (or 81 per cent), followed by Mozambique (a drop of around $2 billion, or 76 per cent). Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia also recorded substantially lower levels of greenfield investment in 2020; although enduring smaller declines in absolute terms, Lesotho, The Gambia, Sierra Leone and Vanuatu all saw their levels of greenfield investment fall by between 93 and 100 per cent.

Figure 37: Changes in the value of announced greenfield FDI inflows to Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020 (US$ million and %)

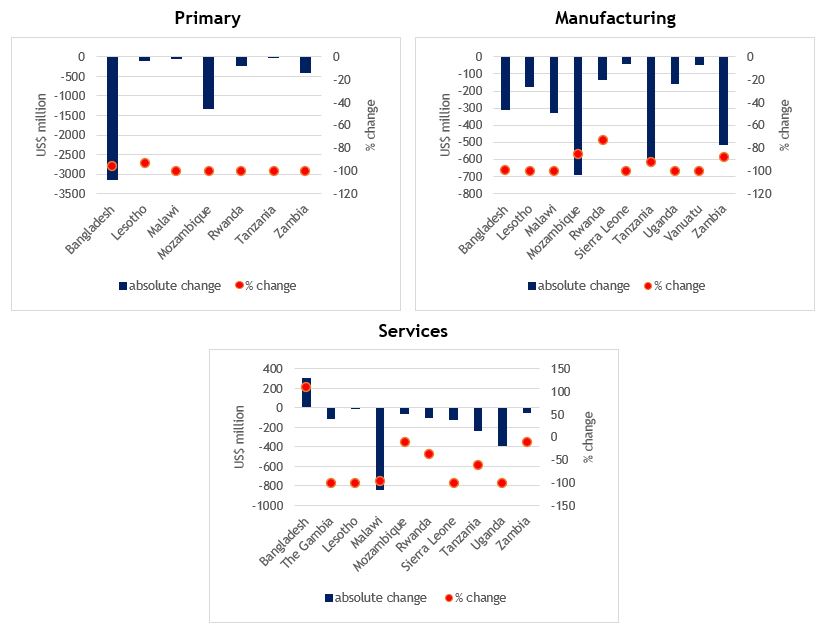

The adverse impact of COVID-19 on greenfield FDI was generally felt across all three broad sectors in Commonwealth LDCs. Bangladesh and Mozambique experienced very large declines in the value of announced investments in the primary sector, totalling more than US$3.1 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively (Figure 38). All seven Commonwealth LDCs that attracted greenfield investment into the primary sector in at least one of the pre-pandemic years (2017-2019) suffered reductions in capital investments in the sector in 2020, with only Bangladesh and Lesotho welcoming new greenfield investment announcements.

Relative to pre-pandemic averages, losses in manufacturing greenfield investment were also severe in 2020. All 11 Commonwealth LDCs receiving greenfield investment in manufacturing in at least one of the three years immediately preceding the pandemic welcomed lower levels of capital investment in 2020. These declines ranged from US$40 million in Sierra Leone and $44 million in Vanuatu to as high as $511 million in Zambia, $614 million in Tanzania and $689 million in Mozambique. Five LDCs – Lesotho, Malawi, Sierra Leone, Uganda and Vanuatu – did not attract any new greenfield investment into manufacturing in 2020. This represents a significant setback to efforts to develop productive manufacturing capacity in these countries.

Only Bangladesh managed to attract more greenfield investment into services in 2020. The remaining nine Commonwealth LDCs either recorded substantial losses in inflows in 2020 relative to pre-pandemic averages (ranging from US$44 million in Zambia to $833 million in Malawi) or did not attract any new investment projects in services in that year (The Gambia, Lesotho, Sierra Leone and Uganda).

Figure 38: COVID-19 impacts on greenfield FDI inflows into broad sectors in Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020 (US$ million and %)

5.4 Other macroeconomic impacts

COVID-19 has severely constrained finance and investment flows globally. This has curtailed inflows of external finance to LDCs, which is especially concerning given they have traditionally relied more heavily on these sources compared with other countries. The United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States (UN-OHRLLS) (2021) estimates that the external financing needs of LDCs more than doubled in 2020 compared with averages for previous years on the back of the economic and social damage caused by the pandemic. The subsections that follow explore the nature and implications of these macroeconomic impacts further.

5.4.1 ODA impacts

COVID-19 has generated uncertainty around future ODA flows as a result of the economic challenges facing developed countries and their implications for the availability of external development resources. The pandemic has also disrupted the implementation of existing ODA-funded projects and programmes in LDCs (UNESCAP, 2021). Nevertheless, ODA flows to the overall LDC group increased by 1.8 per cent in 2020, although this was driven mostly by expenditure on COVID-related programmes and, hence, may not portend a continued increase in development finance flows to LDCs in the longer term (UNESCAP, 2021; UNCTAD, 2021c).

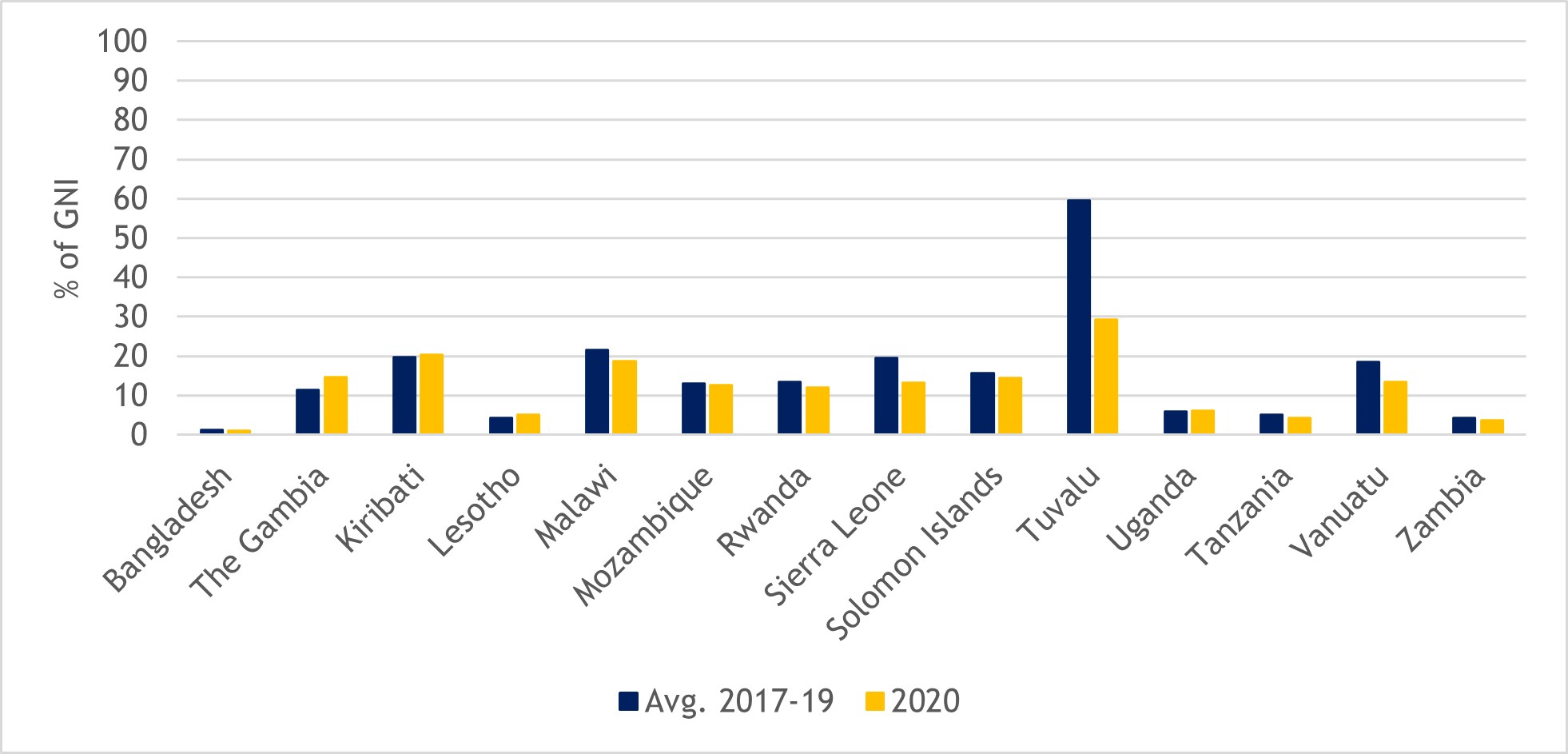

Despite this overall trend, only four Commonwealth LDCs – The Gambia, Kiribati, Lesotho and Uganda – received more ODA in 2020 compared with average pre-pandemic inflows when measured as a percentage of GNI (Figure 39). ODA flows to Tuvalu, which represent a sizable share of GNI, were badly affected, declining by more than 30 percentage points against the pre-pandemic average. In the other Commonwealth LDCs, the impacts varied from modest declines in Bangladesh, Mozambique and Zambia to larger drops – exceeding 5 percentage points – in Vanuatu and Sierra Leone. Given the extent to which many Commonwealth LDCs rely on ODA to finance public expenditure and key development projects (as highlighted in Chapter 4), a sustained decline in these inflows could derail efforts to promote economic diversification, alleviate poverty and generate inclusive and sustainable growth, while also retarding progress towards other targets set out in the SDGs.

Figure 39: ODA received by Commonwealth LDCs as a share of GNI, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020 (%)

5.4.2 Impact on remittances and domestic finances

Chapter 4 highlighted how important remittances are as a source of financial inflows to LDCs. It also showed that flows of remittances to most Commonwealth LDCs were substantial and generally either increased or remained fairly stable during the nine IPoA years preceding the pandemic. Yet COVID-19 has affected remittances overall by reducing demand for migrant workers and through the extensive travel restrictions imposed in both sending and receiving countries to combat the pandemic (UN-OHRLLS, 2021). Across the entire LDC group remittances declined by 2 per cent in 2020 (ibid.).

Despite these concerns, remittance flows to most Commonwealth LDCs were less affected compared with the general trend for the LDC group as a whole. Migrant remittance inflows increased in value in eight Commonwealth LDCs in 2020 compared with pre-pandemic averages, rising by nearly 68 per cent in Vanuatu and by more than 35 per cent in Bangladesh and Zambia (Table 16). Bangladesh remained the largest recipient of migrant remittances in 2020 by a substantial margin. Personal remittances also followed an upward trajectory in more than half the Commonwealth LDCs, rising as a share of GDP in eight countries in 2020 relative to pre-pandemic averages (see the final two columns of Table 16).

However, not all Commonwealth LDCs fared so well. Inflows of migrant remittances were down in Kiribati, Rwanda and Tanzania, and declined by nearly 20 per cent in Lesotho and Uganda in 2020. In turn, personal remittances were between 0.1 and 5 percentage points lower when measured as a share of GDP in Bangladesh, The Gambia, Solomon Islands, Tanzania, Tuvalu and Vanuatu.

Table 16: Migrant remittance inflows (US$ million) and personal remittances received (% of GDP) in Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020

|

Migrant remittance inflows |

|

Personal remittances received |

|

||

|

|

Value in 2020 (US$ million) |

% change 2017-2019 avg. vs. 2020 |

% of GDP in 2020 |

Percentage point change 2017-2019 avg. vs. 2020 |

|

|

Bangladesh |

21,750 |

37.6 |

5.7 |

-0.8 |

|

|

The Gambia |

298 |

26.2 |

12.5 |

-0.6 |

|

|

Kiribati |

19 |

-1.4 |

10.2 |

1.2 |

|

|

Lesotho |

427 |

-19.4 |

21.1 |

1.3 |

|

|

Malawi |

189 |

19.0 |

2.6 |

1.7 |

|

|

Mozambique |

349 |

22.6 |

2.0 |

0.8 |

|

|

Rwanda |

241 |

-1.8 |

2.7 |

0.7 |

|

|

Sierra Leone |

59 |

8.3 |

1.5 |

0.3 |

|

|

Solomon Islands |

28 |

33.8 |

1.4 |

-0.1 |

|

|

Tanzania |

409 |

-1.8 |

0.7 |

-0.1 |

|

|

Tuvalu |

0 |

9.5 |

-1.3 |

|

|

|

Uganda |

1,051 |

-19.7 |

4.1 |

0.6 |

|

|

Vanuatu |

76 |

67.5 |

3.9 |

-5.0 |

|

|

Zambia |

135 |

35.4 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

|

|

Non-CW LDC avg. |

909 |

9.4 |

6.6 |

0.1 |

|

|

Developing country avg. (non-LDCs) |

5,417 |

7.4 |

5.6 |

0.3 |

|

Sources: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using World Bank Migration and Remittances data; World Bank World Development Indicators)

Despite the fall in remittances in some countries, levels of gross domestic savings relative to GDP were generally robust in the majority of the Commonwealth LDCs in 2020. This ratio increased by more than 7 percentage points in Zambia and was also higher relative to pre-pandemic averages in Kiribati, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Sierra Leone and Uganda. That said, The Gambia, Kiribati, Lesotho and Sierra Leone all recorded negative gross domestic savings relative to GDP in 2020, indicative of levels of consumption expenditure in excess of output and continuing the trend witnessed in the latter three countries during the pre-pandemic IPoA years (see Chapter 4). In addition, moderate declines in the ratio of gross domestic savings to GDP were observed in Bangladesh, The Gambia and Rwanda in 2020. If sustained, this may increase these countries’ level of reliance on FDI, loans, remittances and other external financial flows to boost economic growth.

Table 17: Gross domestic savings as a share of GDP in Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020

|

|

2020 (%) |

Percentage point change 2017-2019 avg. vs. 2020 |

|

Bangladesh |

22.8 |

-1.3 |

|

The Gambia |

-2.7 |

-1.7 |

|

Kiribati |

-50.7 |

2.6 |

|

Lesotho |

-12.3 |

2.3 |

|

Malawi |

4.8 |

2.4 |

|

Mozambique |

12.6 |

3.2 |

|

Rwanda |

10.3 |

-3.8 |

|

Sierra Leone |

-8.2 |

2.3 |

|

Uganda |

19.6 |

1.0 |

|

Zambia |

44.4 |

7.6 |

|

Non-CW LDC avg. |

11.7 |

1.6 |

|

Developing country avg. (excl. LDCs) |

22.3 |

1.7 |

Note: No data for Tanzania (2020) and Vanuatu (2017-2020).

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using World Bank World Development Indicators data)

Commonwealth LDCs face even more compromised fiscal positions because of COVID-19. Fiscal constraints in LDCs, marked by high levels of external debt and generally limited financing from external private sources, have severely hampered their ability to mount fiscal responses to the pandemic (CDP, 2021; UN-OHRLLS, 2021). Across all LDCs, increases in direct and indirect fiscal support amounted to just 2.6 per cent of their GDP (or only US$17 per capita), compared with an average of nearly 16 per cent (or $10,000 per capita) in developing countries (UN-OHRLLS, 2021). The world’s developed economies have spent nearly 580 times more than LDCs, in per capita terms, through fiscal responses to the pandemic (ibid.).

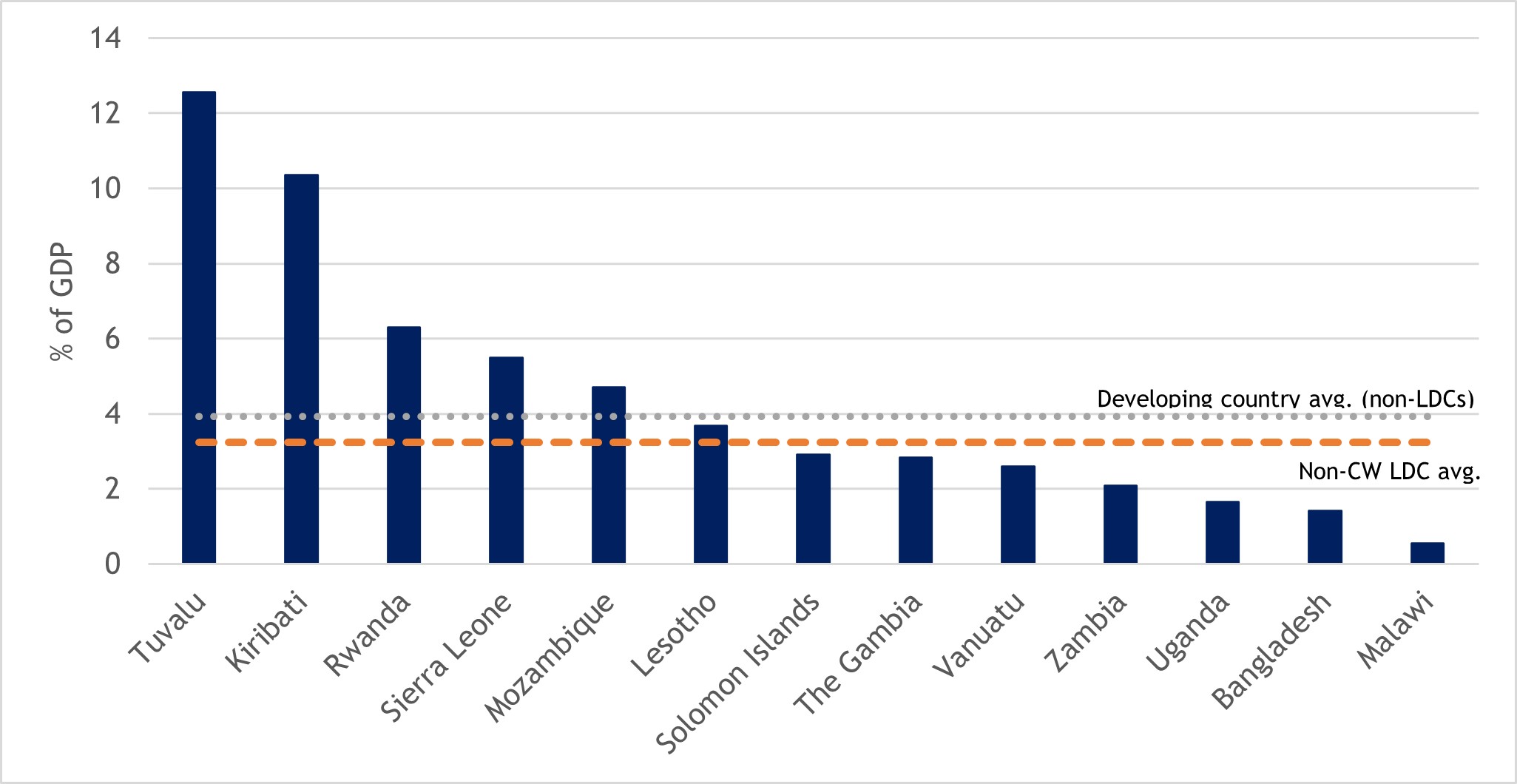

Despite the divergence in capacity to respond with fiscal measures, some Commonwealth LDCs have recorded significant additional spending and/or forgone revenues since January 2020. This amounted to more than 12 per cent of GDP in Tuvalu and more than 10 per cent in Kiribati (Figure 40) and was higher than the averages for non-Commonwealth LDCs (3.2 per cent) and other developing countries (3.9 per cent) in Lesotho, Mozambique, Rwanda and Sierra Leone. This represents a worrying additional burden for those LDCs that were already facing significant financial constraints.

Figure 40: Additional spending or foregone revenues in Commonwealth LDCs since January 2020 (% of GDP)

5.4.3 Debt implications

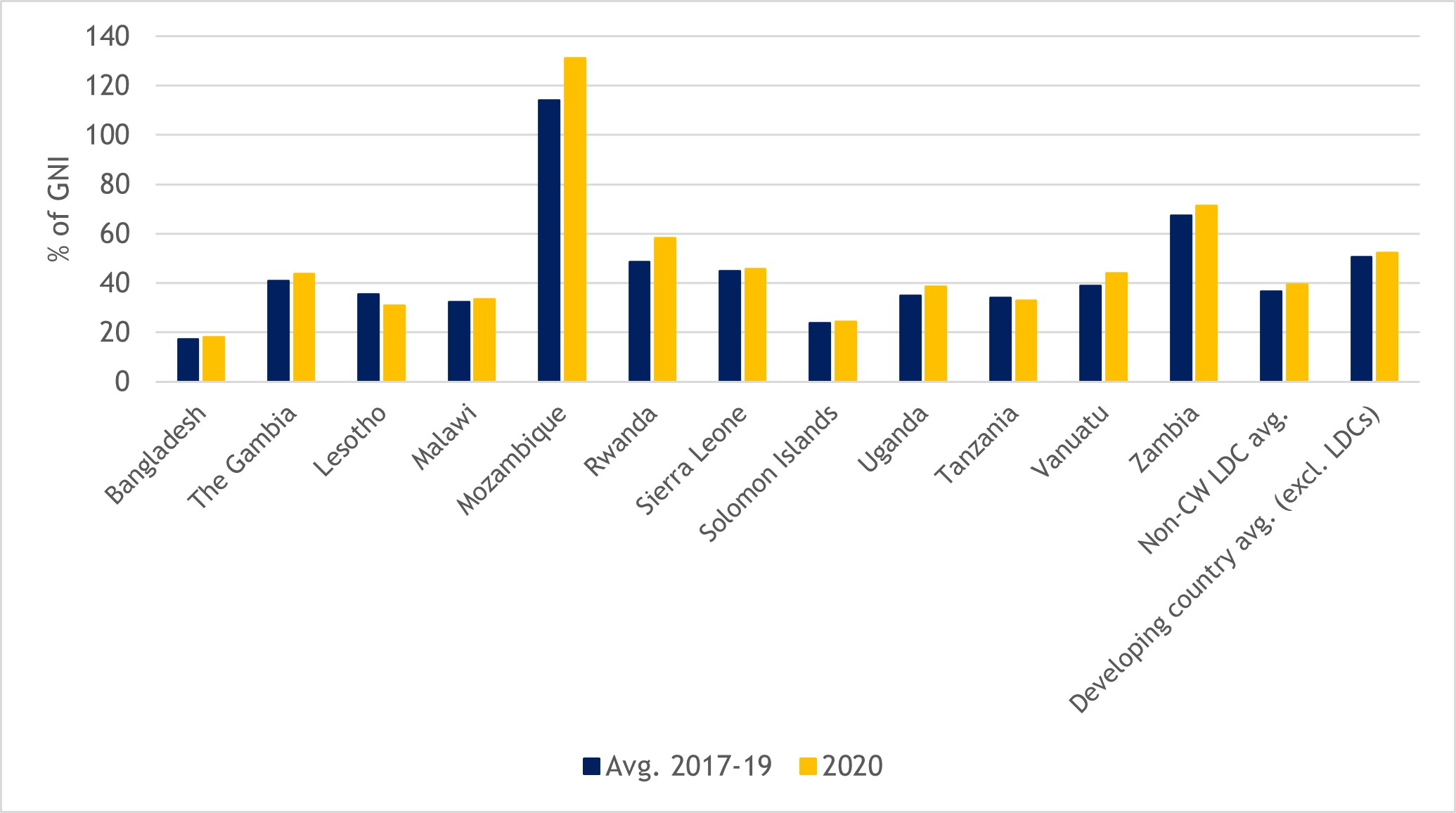

Faced with dwindling flows of other financial resources, external debt – which had already reached alarmingly high levels in a number of African LDCs (especially Mozambique) during the first nine years of the IPoA – increased relative to GNI in all but two Commonwealth LDCs (Lesotho and Tanzania) in 2020 compared with pre-pandemic averages (Figure 41). In Mozambique, the ratio of external debt to GNI rose by 17 percentage points to reach 131 per cent of GNI. This ratio increased by 3.4 percentage points, on average, across all 14 Commonwealth LDCs in 2020, compared with 2.8 per cent for non-Commonwealth LDCs and 1.8 per cent for other developing countries.

The cost of non-concessional borrowing has increased drastically since the start of 2020, especially for commodity-exporting LDCs such as Zambia, compounding concerns about the rising levels of external debt (UN-OHRLLS, 2021). Against this backdrop, Zambia was the first LDC to default on its debt obligations during the pandemic (ibid.). The Debt Service Suspension Initiative introduced by the G-20 countries has provided some relief to the most pressing financial pressures facing LDCs but is not sufficient on its own (CDP, 2021). Consequently, the prospect of a looming debt crisis, which was present even before the emergence of COVID-19, has become a greater possibility as the pandemic has taken hold (UNCTAD, 2019, 2020b, 2021c).

Figure 41: External debt of Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020 (% of GNI)

5.4.4 Impacts on employment

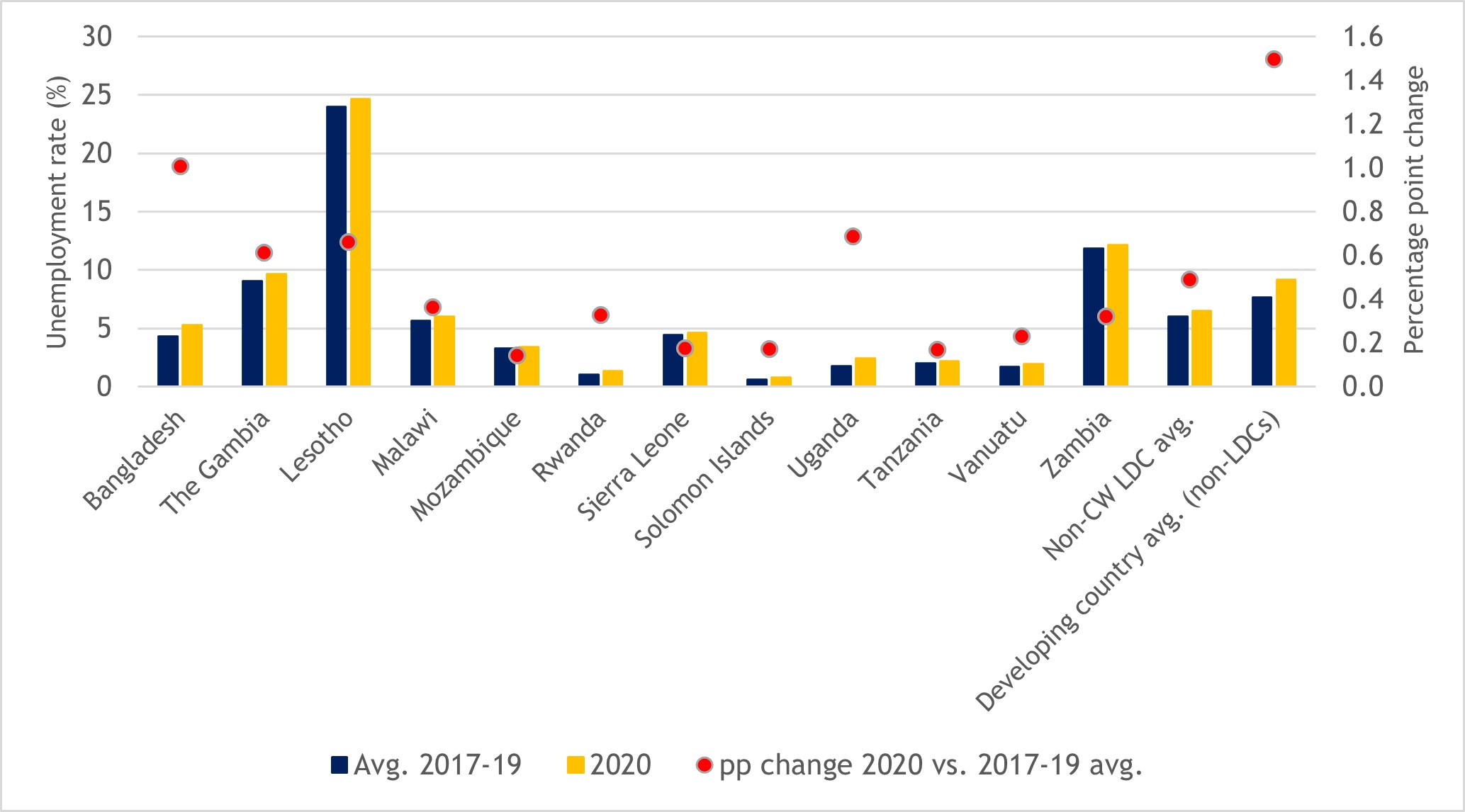

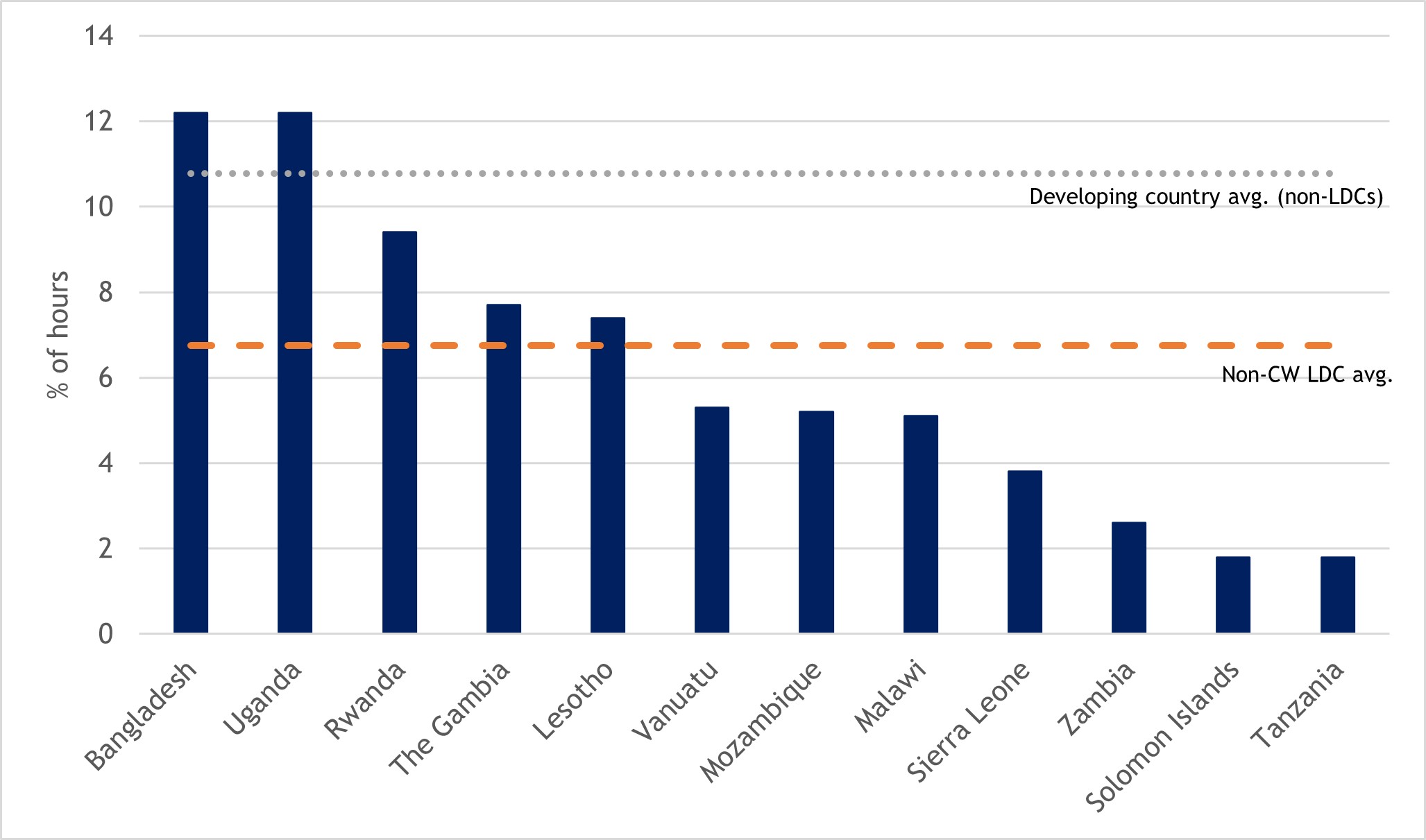

Across the LDC group as a whole, an estimated 17.7 million full time jobs were lost in 2020 (UNESCAP, 2021). Unemployment rates edged up in all 12 Commonwealth LDCs with available data relative to pre-pandemic averages and increased by more than half a percentage point in The Gambia, Lesotho and Uganda (Figure 42). Among these countries, the unemployment rate remained highest by a considerable margin in Lesotho in 2020.

Alongside rising unemployment levels, several Commonwealth LDCs also suffered significant losses in working hours in 2020 as the COVID-19 crisis caused major disruptions to labour markets. These losses exceeded 12 per cent, on average, in Bangladesh and Uganda, and were also above the average for non-Commonwealth LDCs in Rwanda, The Gambia and Lesotho (Figure 43).

Figure 42: Unemployment rates and changes in Commonwealth LDCs, 2017-2019 average vs. 2020

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using World Bank World Development Indicators data)

Figure 43: Working hours lost in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 crisis (%)

Source: ILO modelled estimates

5.5 Implications for a new programme of action for LDCs

Against this backdrop, the medium-term economic outlook, at least for LDCs generally, remains subdued. Their sluggish growth performance is expected to persist in the medium term as several factors constrain output (UNCTAD, 2021c). These include limited government capacity to implement growth-oriented structural policies and fiscal rescue packages in response to the pandemic; continued delays to investment plans; disruptions to education, which, if they persist, may erode human capital accumulation; job losses and bankruptcies; and the ongoing restructuring of value chains, with greater emphasis on near-shoring and re-shoring, which threatens to undermine the competitiveness of key sectors for LDCs, such as garments (ibid.).

These factors are likely to exacerbate the pre-existing structural vulnerabilities that continue to constrain LDC economies. If weak economic growth in LDCs is sustained, it is expected to significantly harm progress in building productive capacity, alleviating poverty and improving living standards, all of which will derail their prospects for achieving the SDGs.

[1] US$1.2 trillion.

[2] A sharp increase in the demand for copper offset the decline in services exports from Zambia.

[3] Global merchandise exports dropped by 7.5 per cent, whereas those from Commonwealth LDCs shrank by more than 10 per cent.