By Dr Mohamed Z M Aazim, Adviser, Debt Management Unit, Commonwealth Secretariat.

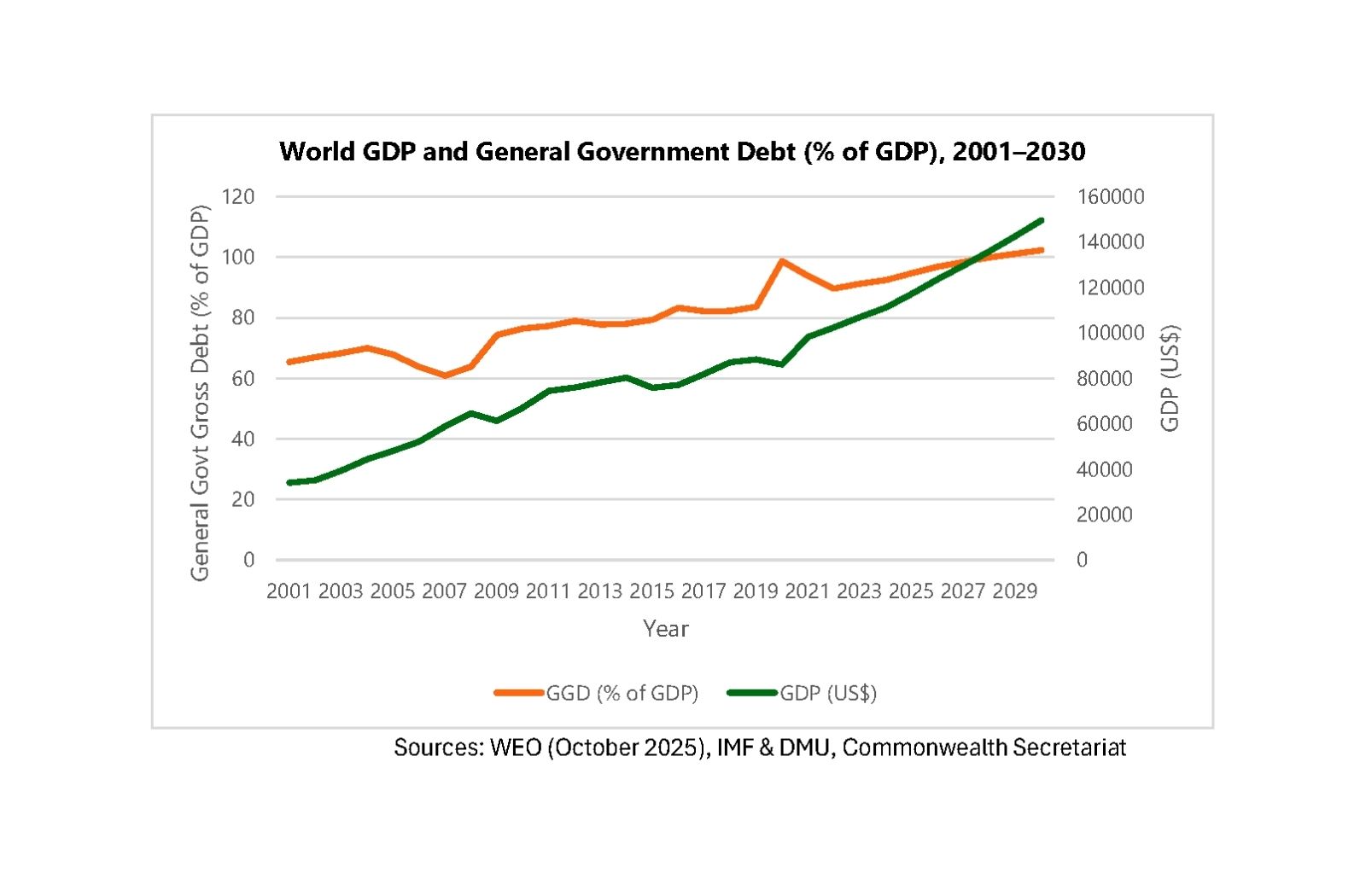

Today, global public debt is approaching an astonishing $100 trillion. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), if current trends continue, by 2029 the total amount of public debt could exceed the size of the entire global economy—a level not seen since the aftermath of World War II.

This isn’t just a problem for a few nations. Major economies such as the United States of America, China, Japan, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy already have debt levels that match or surpass their annual economic output.

Debt isn’t just a problem for poor countries

In a recent blog post, Lagging Growth, Surging Debt: A Commonwealth Snapshot, we highlighted how Commonwealth countries face high debt burdens and need a comprehensive approach, fiscal discipline, debt reprofiling, and, where necessary, restructuring.

But this is no longer just a challenge for low-income countries.

Wealthier nations are borrowing heavily, too. The United States of America owes $38 trillion, roughly 125% of its GDP. The UK has one of the highest borrowing costs among advanced economies, with a budget deficit of over 5% of GDP and public debt equal to its output, leaving little room for responding to future shocks.

What’s driving this surge?

Global GDP is growing, but debt is growing faster. During the pandemic, governments borrowed massively to support economies, pushing global debt above 90% of GDP. While growth has since improved, debt continues to climb. If trends continue, global public debt could top 100% of world’s GDP by 2029, marking a historic high.

Governments borrow to finance the gap between their expenditures and revenues— primarily from taxes and other income sources. This borrowing helps them meet immediate financial needs while maintaining essential public services.

Generally, governments may borrow from international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, other sovereign states, banks and financial intermediaries, and private investors—typically through the issuance of government bonds.

Borrowing can be a strategic tool when used to invest in long-term development priorities that stimulate economic growth and improve public welfare.

However, borrowing becomes a problem when funds are channelled toward consumption or politically motivated spending. In such cases, debt can accumulate rapidly and pose risks to fiscal stability.

Debt challenges in Commonwealth countries

Even wealthier nations, which once borrowed in domestic currencies at low interest rates, now face variable and higher interest rates. They must allocate a sizable share of revenue to pay down debt and cover interest costs as obligations accumulate.

Commonwealth countries collectively owed $13.7 trillion in public debt in 2025 (over 87% of GDP), and this figure is projected to rise to about $17 trillion by 2029, with little change in the debt-to-GDP ratio. But within the accumulation of debt, the main culprits are advanced Commonwealth countries.

When debt grows faster than the economy, countries struggle to pay it back. This can lead to higher taxes, cuts in public services, economic instability, and pressure on households and businesses to cover rising costs. When countries cannot repay, they are forced to restructure, seek bailouts, or give up control of key assets.

Our call to collective action

Global public debt is at unsustainable levels and must be managed carefully. Countries should borrow wisely, investing in areas that create growth, such as infrastructure and education.

Multilateral lenders should also offer fairer terms, especially to poorer nations, while governments must ensure transparency and responsible debt management.

To help Commonwealth countries reduce debt service volatility, the Secretariat continues to promote the development of domestic debt markets, sourcing finance from local lenders, and accessing international financial markets armed with careful analysis.

Additionally, we continue to advocate for improved cooperation between borrowers and lenders. Commonwealth nations must work together to negotiate better terms and push for reforms that make borrowing more sustainable.