By Brendan Vickers, Head, International Trade Policy Section; Salamat Ali, Economic Adviser, Trade Economist and Neil Balchin, Economic Adviser, Trade Policy Analysis, The Commonwealth Secretariat, London.

Food security has emerged as another crisis within the multiple and overlapping set of crises affecting small states. A significant proportion of the 33 million citizens of Commonwealth small states (CWSS) are on the verge of hunger and malnutrition. Small states’ unique economic, structural and environmental vulnerabilities mean they often confront obstacles to producing essential foods domestically and sourcing supplies from the international market.

Around 11 million people residing in seven African small states suffer from high levels of food insecurity. FAO estimates for 2019 indicate almost one-third of the populations of Namibia (32.1%) and Eswatini (30.8%) face severe food insecurity, as do more than one-quarter of those living in Lesotho (27%) and The Gambia (25.7%), and more than one fifth in Botswana (22.2%). The COVID-19 pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war related disruptions to food trade have further exacerbated this already alarming situation.

Commonwealth small states’ excessive reliance on imported food products

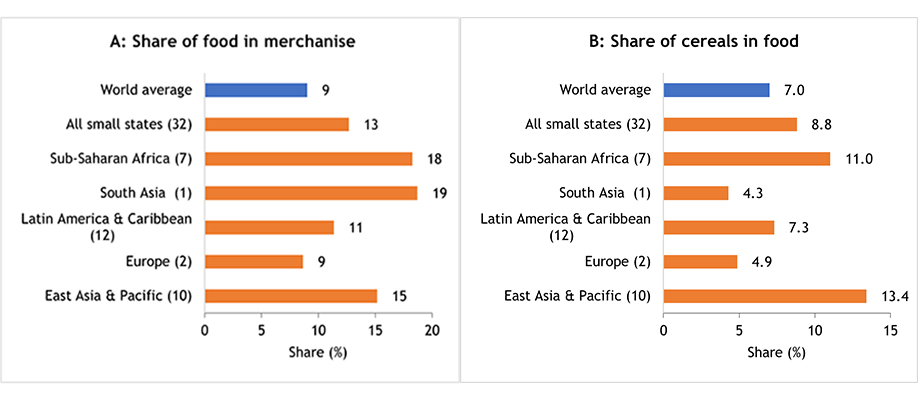

With limited agricultural production capacity, most small states — including 32 that are members of the Commonwealth — rely heavily on imports to fulfil their food security requirements. Food products account for 13 per cent of overall merchandise imports across the 32 CWSS, compared to the world average of 9 per cent (Panel A in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Commonwealth small states’ food import dependency

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WITS data)

These shares are even higher among CWSS in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), East Asia and the Pacific. For four small states — Tonga (35.5%), Kiribati (31%), The Gambia (30.6%) and Lesotho (25.2%) — food items represent more than a quarter of all merchandise imports (Table 1). This excessive reliance on global markets renders them especially vulnerable to trade disruptions generated by external shocks like the war in Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic.

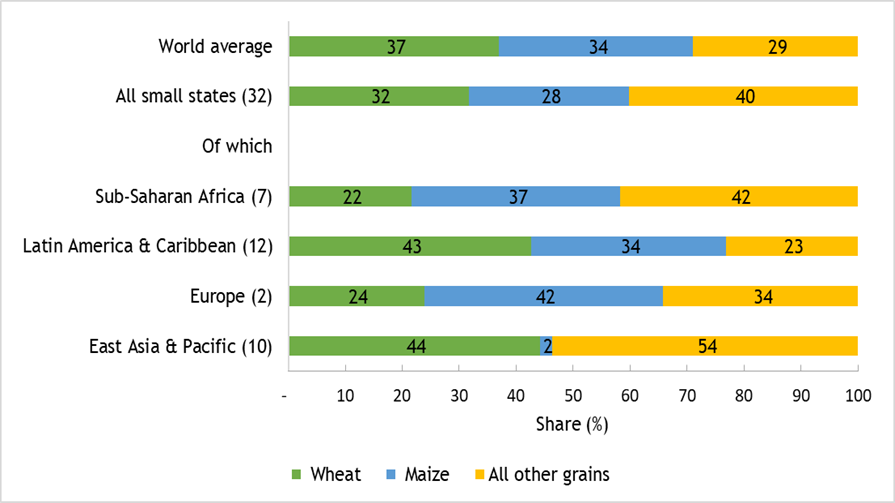

Cereals are an important component of the food imported by most CWSS (Panel B in Figure 1), especially those in East Asia, the Pacific and SSA. Wheat and maize — the prices of which have surged over the past two years — constitute nearly two-thirds of cereals imported into these countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Shares of wheat, maize and other grains in cereals imported by Commonwealth small states

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WITS data)

Implications of the war in Ukraine for food production and trade

The war in Ukraine has created large-scale global supply chain disruptions, with severe consequences for food security far beyond the conflict zone. Both countries are key suppliers of staple foods internationally. They collectively account for more than half of the world’s exports of sunflower oil, one-quarter of worldwide wheat exports and more than 15 per cent of global exports of cereals.

Damage to road networks, major blockages at ports and sanctions imposed on Russia have combined to hamper production, cripple agricultural supply chains and halt — or severely constrain — food exports from this region.

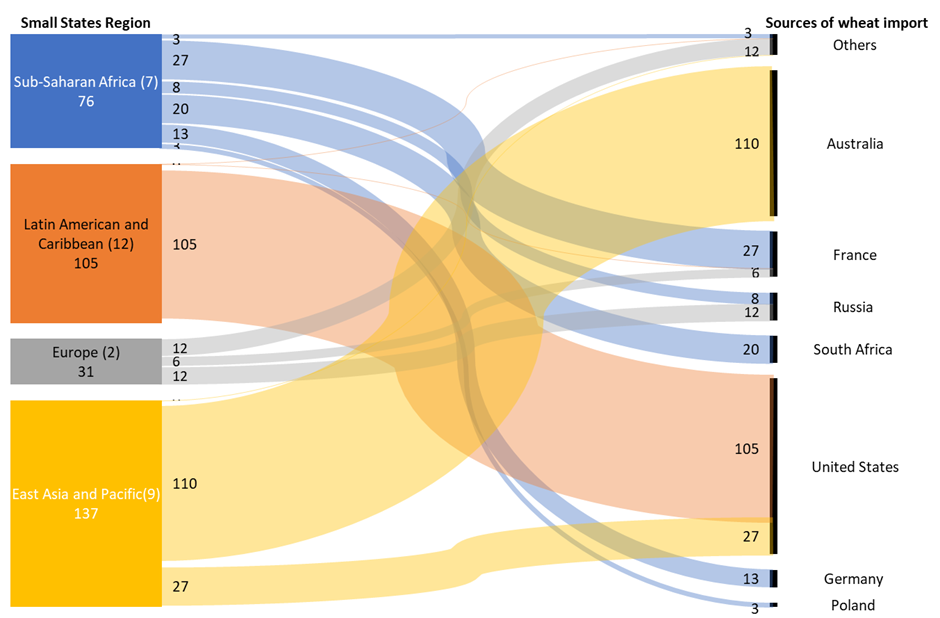

Fortunately for most Commonwealth small states, their direct dependence on Russia and Ukraine for staple food imports is quite limited: 32 CWSS collectively source about 9% of their wheat from Russia; much lower than Russia’s share of global wheat exports (15%). Their wheat imports are relatively diversified, with large shares held by big regional producers, although there is regional variation (Figure 3).

Some CWSS are notably more exposed than others. For instance, Cyprus, Malta, The Gambia and Namibia source more than 40 per cent of their wheat from Russia. Cyprus imports around 20 per cent of edible oils from Ukraine, whereas The Gambia imports around 12 per cent from that country. The conflict in Ukraine therefore poses a more direct threat to food security in these four countries.

Figure 3: Main sources of wheat imports for Commonwealth small states

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (calculated using WITS data)

For most CWSS, the impacts of the conflict in Ukraine, coming on the back of the COVID-19 pandemic, are most likely to be felt indirectly through rapidly escalating food prices and wider inflationary pressures. Disruptions to trade and global supply shortages are putting significant upward pressure on the prices of commodity crops like wheat, as well as inputs such as fuel, which have knock-on effects on prices across food production and supply chains. Food prices are an important part of the food security equation — higher prices mean food is less affordable, raising the threat of food insecurity in resource-constrained small states, particularly for low-income households.

Fertiliser shortages (Russia and Ukraine supply around 15 per cent of global fertiliser stocks) could worsen the situation by drastically reducing crop yields in major food-producing countries. Like the limited direct effects through the food import channel, the direct effect of the conflict in Ukraine on access to agricultural inputs is also likely to be relatively muted for most CWSS. They collectively source just 2.4 per cent of their fertiliser imports from Russia and Belarus (which shares land borders with both Russia and Ukraine), and 25 small states did not import any fertiliser from these two countries in 2019. However, domestic agricultural production in Dominica, which relies on Russia and Belarus for 62 per cent of its fertiliser imports, as well as Brunei Darussalam (17%) and Fiji (14%), could be affected if inflows of fertilisers remain curtailed for an extended period.

Export restrictions imposed by some countries in response to COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine pose an additional threat to food supplies for heavily import-dependent small states. As many as 52 countries had imposed export restrictions as of mid-May 2022 citing food security concerns, meaning even small states relatively unexposed to blockages affecting imports from Russia and Ukraine may still face difficulty securing sufficient imports of basic food items.

Other compounding factors threatening food security

The war in Ukraine is not the only factor affecting food supplies. Earlier, COVID-19 impacted both food production and supply chains. Lockdowns and other restrictions disrupted the supply of labour for agriculture and food production and constrained access to key agricultural inputs such as seeds, fertilisers and insecticides. In some small states, a shortage of storage facilities has resulted in significant losses in agricultural produce.

The pandemic has also disrupted trade in food products through market closures, export restrictions and supply chain disruptions, thereby placing considerable pressure on small states relying on imports to meet their food security needs. The indirect effects of the economic devastation caused by the pandemic — reflected in diminished revenues, foreign exchange earnings and remittances — have further restricted the ability of some small states to finance imports of food and agricultural inputs.

Apart from the lingering effects of the pandemic, extreme weather events continue to plague food production in many countries. Recurrent droughts have devastated crop and livestock production in many small states in Africa, including Namibia. Cyclones, hurricanes and other natural disasters pose ever-present threats to small islands in the Caribbean and Pacific. Cyclone Harold, for instance, caused widespread destruction in Fiji, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu in April 2020, resulting in extensive damage to the agriculture sector, particularly in Vanuatu. In April 2021, the eruption of the La Soufrière volcano in St Vincent and the Grenadines triggered a humanitarian crisis and decimated crops.

Addressing the food insecurity challenge in small states

Solutions to food security challenges need to be grounded in greater coherence and coordination nationally, regionally and globally. Progress in three immediate priority areas could help to bolster food security in small states:

- Maintain open trade in food products. Fair and transparent market access for agricultural products and inputs, along with the elimination of non-tariff barriers affecting agricultural trade are vital to maintain well-functioning food supply chains and ensure efficient cross-border trade in food products. Countries should also be encouraged to avoid implementing unnecessary restrictions on exports of basic food items. In this vein, it will be important for WTO members to hold firm on commitments made at the organization’s Twelfth Ministerial Conference to avoid WTO-inconsistent export prohibitions or restrictions on agri-food trade.

- Expand local food production capacity. This requires improved market conditions and greater support to small-scale farmers. Investments in food production and infrastructure supporting agricultural supply chains need to be upscaled. Dedicated support is also required to assist farmers and downstream food processors to harness new technologies, especially digitalisation, to help boost yields and productivity.

- Improve sustainability and foster resilience in national food systems. The long-term viability of food production in small states depends critically on the protection of their delicate agricultural ecosystems. This requires pro-active initiatives to preserve and promote biodiversity, conserve water and prevent soil degradation, alongside work to strengthen sustainable management of food value chains and develop more environmentally sustainable agricultural production methods. These interventions will help to enhance climate resilience across food systems in small states.

Media contact

- Rena Gashumba Communications Adviser, Communications Division, Commonwealth Secretariat

- T: +44 7483 919 968 | E-mail