Commonwealth Europe

6.1 Overview of agriculture in commonwealth countries in Europe

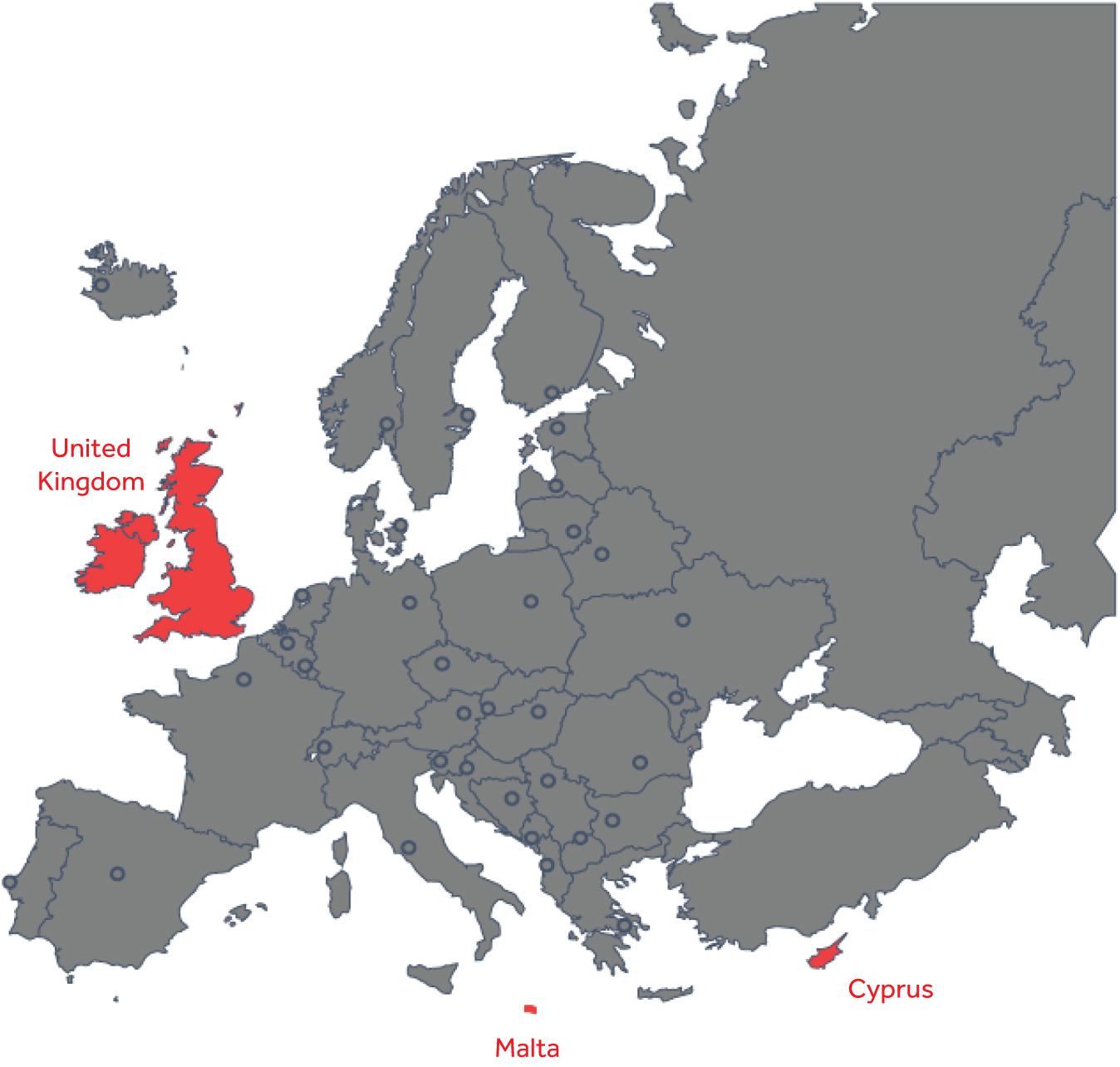

Figure 6.1: Map of Europe showing Commonwealth countries

There are three Commonwealth member countries in Europe, all of which are island countries. In these, the average agriculture, forestry and fishing value added ( per cent of GDP) is 1 per cent. Additionally, the sector employs 1.49 per cent of the population.[1]

Despite the limited contribution to GDP and employment, the agriculture sector is important to the economies of Commonwealth Europe, as it has a direct impact on food security and livelihoods.

6.1.1 CYPRUS

- Agriculture holdings in Cyprus are organised in parcels, with a given holding owning a given number of parcels of land. The average number of parcels (2003 data) is five and the average size of a parcel is 0.7 hectares. Based on this, the average land size per holding as of 2003 was 3.5 hectares.[2] In 2010, the average land size per holding was reduced to 3.0 hectares.

- Most (74 per cent) of the holdings in Cyprus operate on small land sizes of 0.1 ha to 1.9 hectares.

- Agriculture in Cyprus is characterised by farming on rented land (52 per cent), owned land (46 per cent) and in partnership between the landlord and the sharecropper under a written or oral share-farming contract (2 per cent).

6.1.2 MALTA

- Agriculture in Malta is characterised by small-scale family production. The average size of agriculture holdings in the country is 0.9 hectares.

- Family labour accounts for 90 per cent of volume of agriculture work.

- Family holdings can be owned by the farmer (23.8 per cent) or rented (76.2 per cent).[3]

6.1.3 UNITED KINGDOM

- In England and Wales, around 33 per cent of all agricultural land is rented. The remaining 77 per cent is farmed by the actual owners.[4]

6.2 Systemic constraints to agriculture in Commonwealth Europe

6.2.1 Climate vulnerability and agriculture productivity

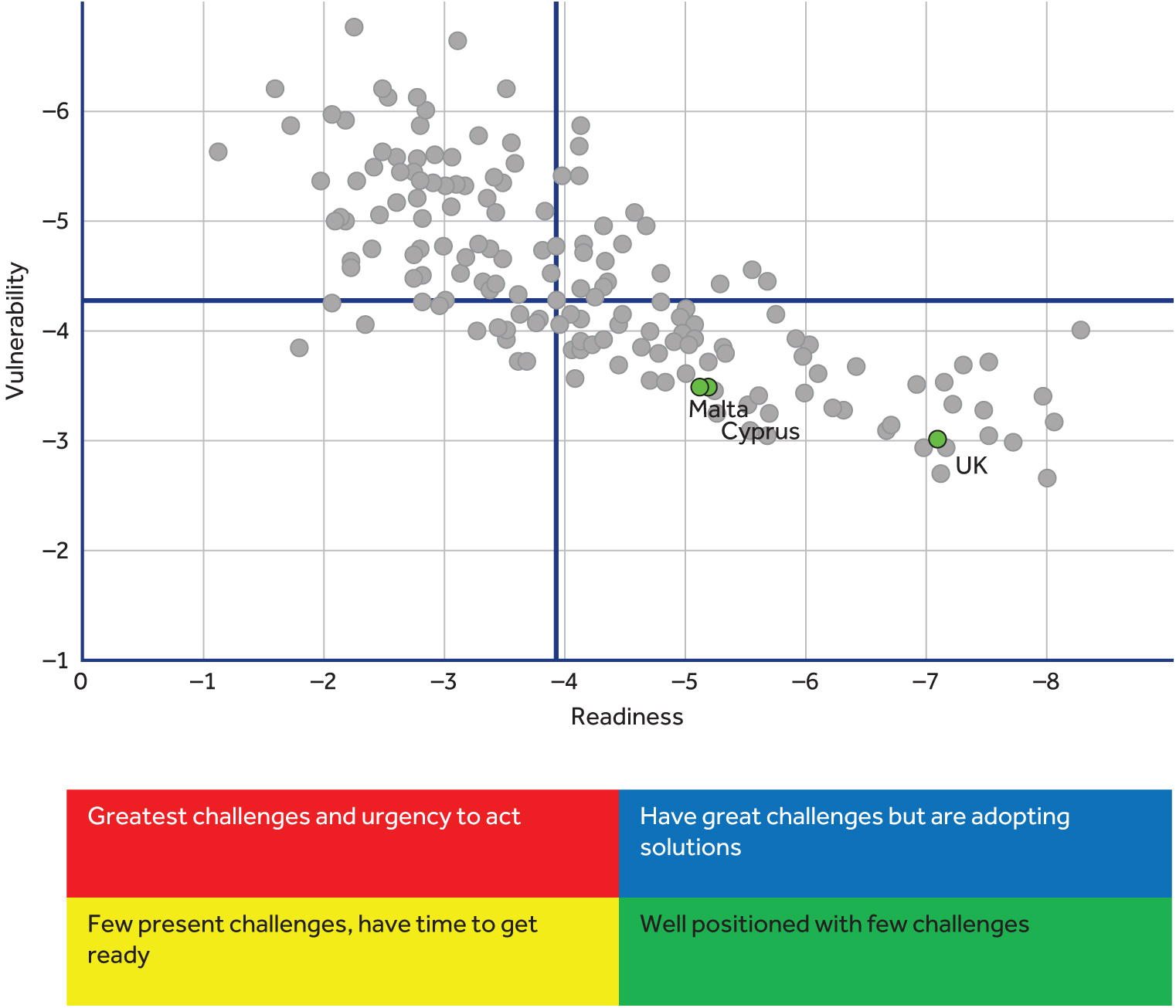

To show the level of vulnerability to climate shocks and readiness to respond to these shocks, the ND-GAIN Matrix is used. The matrix provides a visual tool for quickly comparing the current state of climate vulnerability and readiness of different countries.

All the three countries in Europe that are members of the Commonwealth have low levels of vulnerability to climate change and a high level of readiness. Although none of them have a perfect vulnerability score, these countries still need to adapt and are well positioned to do so.For example, though the agriculture sector in Cyprus is reliant on irrigation (70 per cent of the country’s valuable water sources are used for agriculture irrigation), the country has managed to adapt to the water shortage situation by setting up water desalination plants. The country has six desalination plants through which it can be self-sufficient.Additionally, there is extensive use of modern micro-irrigation systems, which practically cover 90 per cent of the irrigated area.

Additionally, even though Malta’s geographical location as an island state makes it extremely vulnerable to climate shocks such as floods, the Maltese Ministry of Resources and Rural Affairs in 2012 put forth the National Strategy for Climate Change and Adaptation in a bid to prepare the country for the impacts of climate change. The adaptive measures put in place by the countries are one of the reasons why productivity is much higher as compared to other regions like Africa where there are limited measures to respond to the effects of climate change.

Figure 6.2: Current state of climate change vulnerability and readiness of Commonwealth countries in Europe to respond to climate shocks

Source: Notre Dame Global Adaption Index, 2017.[5]

6.2.2 Gender mainstreaming in agriculture

Gender mainstreaming at a policy and government programming level: Throughout the three Commonwealth countries in Europe, there is gender mainstreaming at the policy level.

- For the case of Malta and Cyprus, as members of the European Union, they are required to consider the situation for women in rural areas when developing their rural development programmes.

- All three countries typically disaggregate key agriculture sector indicators by gender.

Women engagement in the agriculture sector. In Cyprus and Malta, women are critical to the agriculture sector. The family-based nature of agriculture production means that women play an important role in production activities. Women mostly participate in cultivation and animal rearing; 23 per cent of women in Cyprus and 6 per cent in Malta are farm managers. This is below the 29 per cent average for the European Union.

In the United Kingdom, there is a disproportionate distribution in the owners of farm assets among male and female. Of the farm owners, only 16 per cent are female, and of these, approximately 77 per cent of the female owners work on their farms in a part-time capacity or not at all. In the same sense, only 17 per cent of the farm managers are female. These statistics point to limited female involvement in the agricultural sector.[6]

However, there is evidence that the number of female farmworkers has gradually increased with The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) reporting just over 25,000 women running farms.[7] More women are enrolled in agricultural courses with a female to male ratio of 2:1.[8]

6.2.3 Youth employment and entrepreneurship

In the United Kingdom, youth participation in agriculture is less as compared to other age groups. As of 2016, only 3 per cent of the farm owners in the United Kingdom were under the age of 35 with the median age being 60.

Table 6.1: Youth participation in agriculture in UK

|

Proportion of owners in each age group |

|

|

Under 35 years |

3 |

|

35–44 Years |

9 |

|

45- 54 Years |

23 |

|

55–64 Years |

29 |

|

65 Years and over |

36 |

|

Median age |

60 |

The Malta Youth in Agriculture Foundation (MaYA) in Malta is a youth organisation primarily founded to unite like-minded youths who are enthusiastic about agriculture in Malta. Some of the objectives of the set-up include protecting the interests of youths in the Maltese islands, promoting sustained and diversified agriculture among others.[9]

Given the reliance of the agricultural sectors of both Cyprus and Malta on family labour, there is a need for improved engagement and involvement of youths in key decision-making aspects to ensure the sustainability of the agricultural labour supply.

6.2.4 Market, trade and supply chain

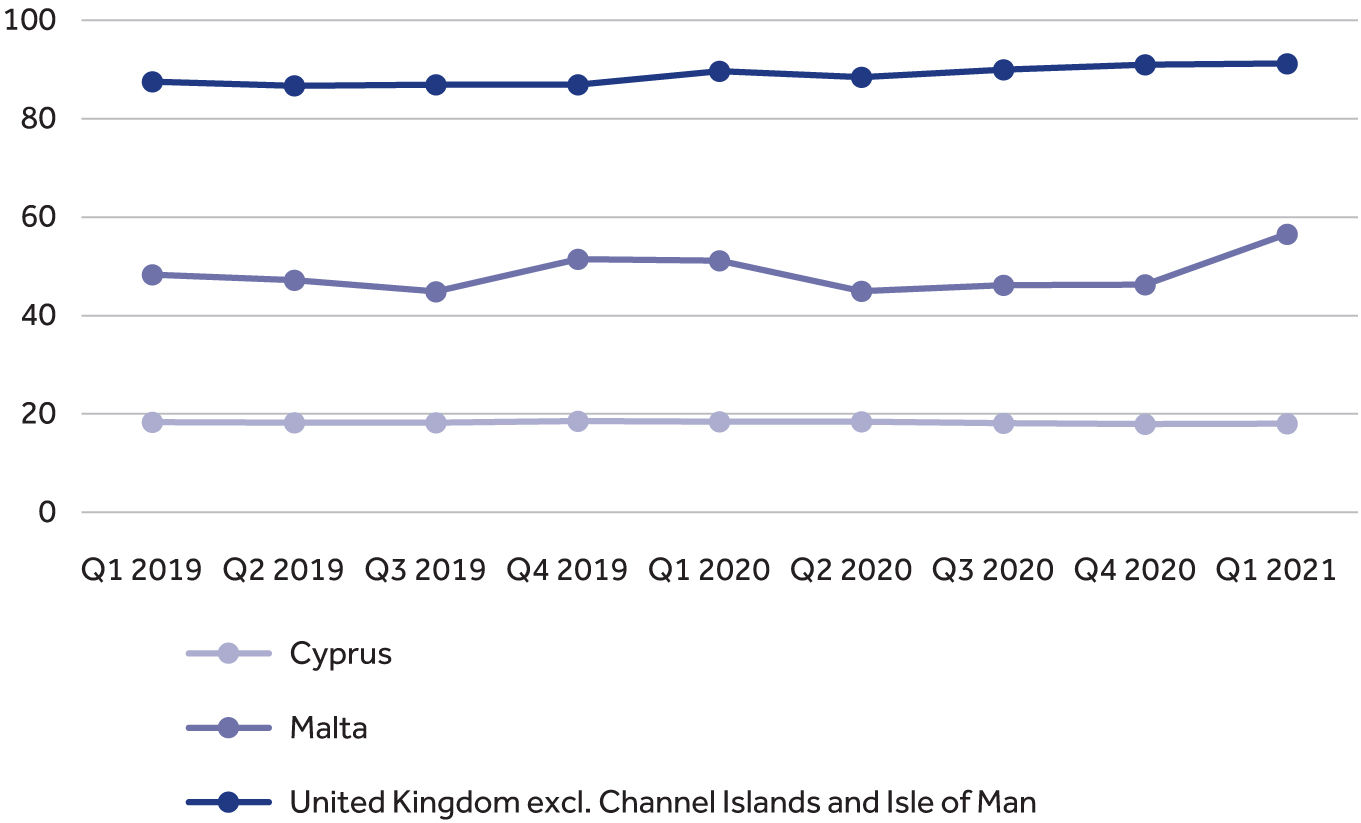

The Liner Shipping Connectivity Index captures the level of integration into the existing liner shipping network by measuring liner shipping connectivity) and is scored with a Maximum score of 100.

Figure 6.3: The Liner Shipping Connectivity Index

Cyprus scores least on The Liner Shipping Connectivity Index among the Commonwealth Europe countries which could point to inefficiencies in the country’s ability to access the global market for produce and inputs. The UK’s position along the coastal lines coupled with advanced transport connectivity signifies ease in accessing global markets for import and export of agricultural produce and inputs among others.

Market Uncertainly and price instability: Recent phenomena such as the outbreak of COVID-19, Brexit among others, have exasperated uncertainties in the market due to fluctuations in production, import and export volumes for most of the Commonwealth European countries. These have led to price fluctuations as the economies come to terms with and attempt to adapt to the new reality.

Case study: Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the agriculture sector in Commonwealth Europe

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Malta and Cyprus

- Disruption in supply chains: Countries such as Cyprus which are heavily reliant on cross-border trade were significantly being hit by the disruption in the global supply chain brought about by the pandemic that has cut the international freight capacity by 80 per cent.[10]

- Reduction in demand due to reduction in tourist activities: The economies of Malta and Cyprus were dependent on the tourism sector. Restriction in international travel and slump in the tourism sector had a ripple effect felt in the agriculture sector.

United Kingdom

- Reduced demand: In the dairy value chain, most farmers sell their produce on a contract basis with the hospitality industry as a major destination. Following the lockdown restrictions, the Royal Association of British Dairy Farmers estimated over 1 million litres of milk disposed of due to significantly reduced demand.[11] The horticultural industry, especially the potatoes industry, was heavily hit with over 20,000 tonnes of potatoes left in stock that was previously destined for the fish and chips trade.

- Labour shortage: Acute shortage of skilled labour to work on farms due to travel restrictions that prevented the movement of seasonal labourers, who usually travel to the United Kingdom on a seasonal basis. Farmers called for the training of the workers pushed out of employment due to the outbreak to form a “land army” to work on farms.

Responses in light of COVID-19 outbreak

Malta and Cyprus (European Union Interventions)[12]

- Seasonal workers were classified as essential workers to enable them to access respective farms.

- Green lanes were established at border crossing points to enable agricultural products among others to be transported to destination markets.

- Farmers were availed loans and guarantees worth 200,000 euros given out at low-interest rates and flexible repayment periods.

- State aid to farmers and food processing companies was increased.

- Rural development funds worth 5,000 euros per farmer and 50,000 euros per SMEs as direct relief following the COVID-19 outbreak were approved.

UK Bounce back plan[13]

- Announced by The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in conjunction with the Department of International Trade (DIT) in the United Kingdom, the “bounce back” plan aimed to help businesses in the agriculture, food and drink industry grow their trade activities hit by the COVID-19 pandemic overseas. Some of the interventions under the bounce-back plan include the following:

- stimulating agri-food industry,

- educational support through the Consumer and Retail Export Academy,

- smart distance selling support,

- showcasing “Brand Britain” at global events,

- financial support, and

- investment strategy planning

UK Pick for Britain Campaign

- The Pick for Britain campaign was aimed at recruiting enthusiastic domestic workers to plug the temporary labour shortages induced by the COVID-19 outbreak. The campaign was however marred by several issues such as unsuitability of the available domestic applicants.[14]

- The FeedTheNation drive was also started with the aim of recruiting and training workers to meet the domestic labour shortages in the food supply system, retail and delivery.[15]

6.3 The state of digital agriculture in Commonwealth Europe

6.3.1 Digital innovations for digitalisation of agriculture in Europe

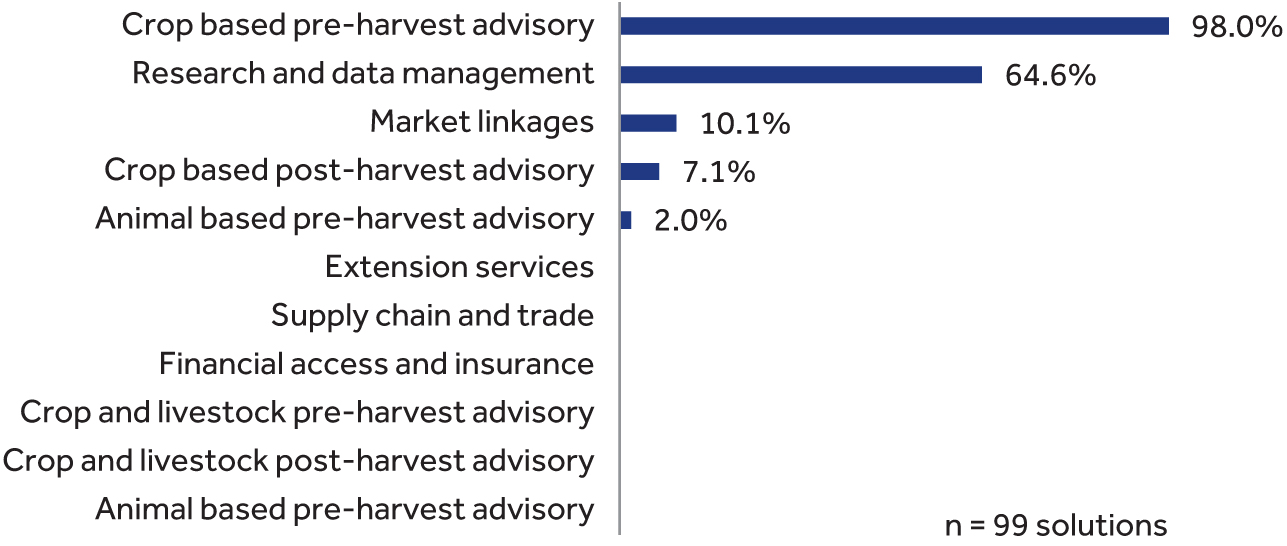

The study assessed 99 digital solutions in the United Kingdom, Malta and Cyprus. The predominant use cases of the mapped solutions and their classification is shown as follows.

Figure 6.4: Distribution of digital solutions by service category

More than half of the assessed solutions have a data management and research component in their product offering. This is similarly the case in Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Other characteristics of digital agriculture solutions in the region

- 95 Per cent of digital agriculture solutions are operated by private entities.

- 94 Per cent of digital agriculture solutions have two service offerings or less. This points to the fact that digital agriculture solutions in the region have more focused value propositions, a different trend from Australia and New Zealand where there is a lot of bundling.

Technologies being utilised in digitalisation of agriculture in commonwealth Europe

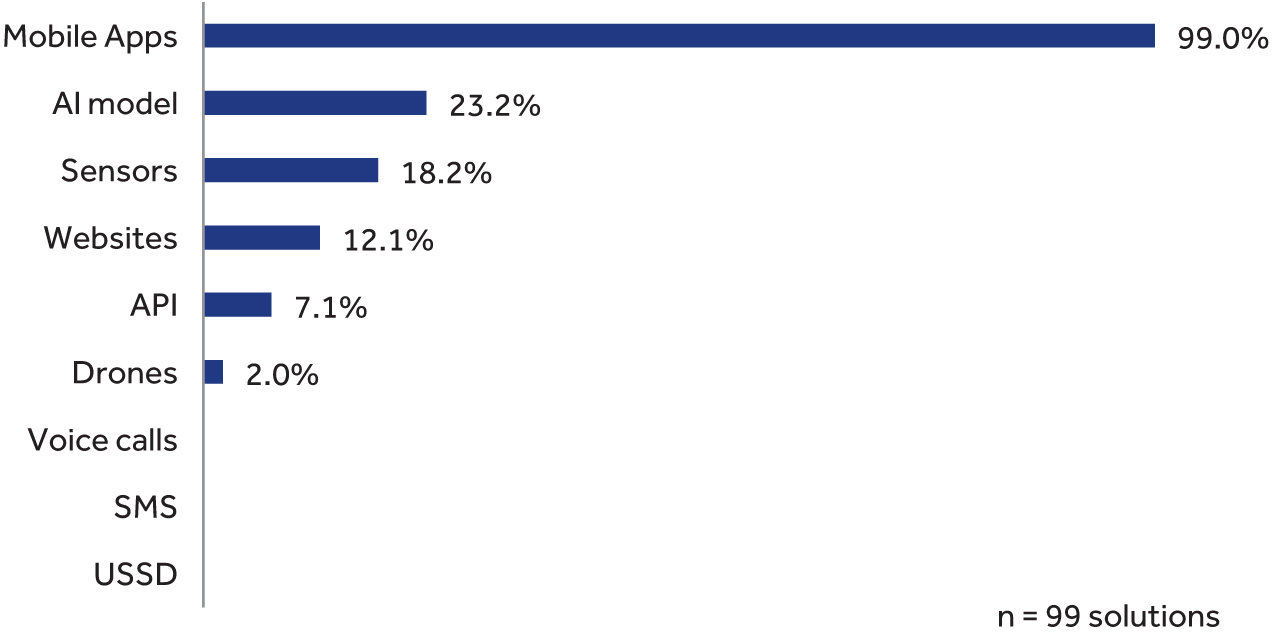

Figure 6.5: Distribution of digital solutions by primary delivery media

Though mobile applications are the most common form of technologies, there is an equally high penetration of smart farming technologies like AI models and sensors. This can be explained by the fact that the United Kingdom, just like Canada, Australia and New Zealand, has large farm sizes that allow for realisation of the value of smart farming. Noteworthy is the fact that an estimated 60 per cent of UK farmers already use[16] some sort of smart farming on their farms, although, for most, this simply means using GPS tractor steering.

Case study: Featured frontier digital agricultural solution in the European Commonwealth countries – Xarivo Field Manager App in the United Kingdom

The Xarivo Field Manager is a digital product developed by Xarivo digital farming solutions. The new digital product supports growers and agronomists to make better-informed decisions on protecting their crops and increasing efficiency and profitability. Field Manager combines the visualisation of field zones with two cutting-edge Spray Timer and Zone Spray features. These provide growers and agronomists with tools for identifying field-specific disease risk and optimising fungicide applications to improve crop production both economically and sustainably. Xarivo offers digital products that deliver independent field-zone-specific agronomic insights and alerts, enabling farmers and agronomists to grow crops in the most efficient way by leveraging algorithms with data from real fields more than 25 years ago.[17]

Value proposition summary

- Current Biomass Maps of field zones, based on analysis and interpretation of real-time satellite data.

- Historic field Power Zone maps based on up to 15 years of satellite data.

- Compare field zone maps for yield, nutrition, crop protection, growth regulators, seeding and soil.

- Detailed 10-day and hourly weather forecast for each of your fields, historic weather data

Product offering details

General outreach – Xarivo Field Manager is part of a suite of digital farming products provided by Xarivo Digital Farming Solutions, which is part of BASF’s Agricultural Solutions Division. The Xarivo offering also includes a Xarivo Scouting app. Launched in the United States in 2018, Scouting supports farmers in efficiently monitoring fields for diseases, weeds and leaf damage using a smartphone camera. The Xarivo Scouting app is available for free in the App Store and Google Play.

Field management solution – The Xarivo Field Manager spray timer delivers recommendations to growers’ mobile devices on the right timing for corn and winter wheat fungicide application by combining multiple variables from field-specific data (geolocation, crop rotation, crop/variety and previous applications) with crop variety data (susceptibilities and growth stage characteristics) and local weather data (air and soil temperature and humidity). This then automatically recommends the optimal spray period and intensity to ensure economic use of the pesticides.

Farmer impact – The Xarivo field manager gives its 30,000 European users access to farm data insights, and more accurate field mapping, the ability to share farm access and a useful overview of farms, enabling better decision-making. Launched in the United Kingdom in (2021) the Field Manager has already amassed 1,100 new users. By working closely with growers and agronomists, Xarivo has enhanced the platform’s accuracy and forecasting abilities.

In summary: how digital solutions are being leveraged to solve systemic constraints

Snapshot on how digitalisation is being used to increase women participation in agriculture in commonwealth Europe

The rise of social media platforms has changed previous perceptions about the agricultural sector such as the misconception that farming is not for the educated, among others. This has attracted more women to the forefront in the agricultural sector.[18] Prominent female farmers in the United Kingdom run social media platforms with thousands of followers, which has also enhanced information transfer to the younger generation.

Snapshot on how digitalisation is being leveraged to improve agriculture sector productivity

As evidenced in the case studies above, the application of smart farming technologies has instilled informed decision-making among farmers, thereby improving their resilience to the uncertainty of seasons. This has in turn had a significant impact on productivity. A mobile application, CROPROTECT,[19] in the United Kingdom helps farmers with guidance on pest, weed and disease management in scenarios where traditional pesticides are not available.

Snapshot on how digitalisation is being leveraged to mitigate the impacts of climate change

Early river sea level and flood warning systems are in place in the United Kingdom that issue general alerts to areas that are most likely to be hit by flooding. This helps farmers prepare beforehand to reduce the impacts of such climate shocks.[20] AI, satellite imagery and drones are being used to monitor glaciers and the impact of climate change in the Arctic.[21] This is one of the components in the multi-pronged fight on climate change globally.

Snapshot on how digitalisation is being used to increase youth employment and entrepreneurship in agriculture in Commonwealth Europe

As a global trend, youth involvement in agriculture has been low with the sector often shunned for its use of manual labour. Innovations, such as use of AI, smart farming, have the potential to attract youths due to the increase in automation and productivity of the sector.

Snapshot on how digitalisation is being leveraged to enhance access to markets

Agrimetrics, a UK company recently launched a machine learning algorithm dubbed “CropLens AI” that can detect crops from space with 90 per cent accuracy.[22]This data can help bridge the information gap in the agricultural sector that is often the cause for speculation and uncertainty fuelling price fluctuations in the market.

6.3.2 Data infrastructure for digitalisation of agriculture in Europe

Data for content

Soil property data: In the United Kingdom, technology is being used to capture soil dat. The Natural Environment Research Council’s British Geological Survey and Centre for Ecology & Hydrology provides the free-to-use mySoil App. It allows farmers to view and upload information about soils in their area and explore vegetation habitat data across the United Kingdom. Since its launch in June 2012, the free app has attracted more than 2.6 million web hits and 12,500 users. More than 500 people have contributed to the databank to build even greater knowledge of soil properties.[23] In addition, there is a Land Information System operated by Cranfield University, United Kingdom that provides soil and soil-related information for England and Wales including spatial mapping of soils at a variety of scales, as well as corresponding soil property and agro-climatological data. This is the largest land information system that is recognised by UK Government as the definitive source of national soils information. In Cyprus and Malta, the European soil data centre has geo-referenced soil information about the various soil attributes in the region.

National agri-statistical data: In the United Kingdom, there is a presence of national agri-statistical data. The Agricultural and Horticultural Census covers about 99 per cent of the total agricultural area and is conducted annually.[24] The European Union also provides regular agri-statistical data for member countries, with the most recent being from the Eurostat 2020 agricultural survey. This survey includes all European Commonwealth member states.

Weather data: The UK Government has its weather data and forecasts distributed through Government APIs. This in effect means that digital solution developers have access to updated weather data that can be included in digital agricultural solutions. Additionally, numerous private entities provide weather data at a fee. Both the Cypriot and Maltese authorities collect data on weather and atmospheric conditions. This data is however not distributed to the private sector through open APIs.

Identity systems

Primary identifiers for farmers: In the United Kingdom, state-issued identity cards were scrapped by the Government in 2011. While there is no state-mandated farmers’ register, farming entities can still be registered as business entities. By 2020, over three quarters (80 per cent) of farms had a government-issued gateway ID and almost a third (32 per cent) had a Government Verified ID.[25] The Government of Malta has a national farmers’ register that offers personalised web-based access to the Land Parcel Identification System (IACS).[26] In Cyprus, there is no state-mandated farmer register, although the Government issues a digital identification card.

6.3.3 Business development for digitalisation of agriculture in Europe

Financing sources for digital solutions: While there is a general lack of specific data that elaborately states the funding options for digital agricultural solutions in the European Commonwealth countries, postulations can be made based on observations from countries with similar commercialised farming systems. As with other nations with high per capita gross national incomes, European Commonwealth countries have digital agricultural spaces that benefit greatly from the presence of large agricultural machinery manufacturers. These machinery manufacturers include substantial operations by some of the world’s leading agri-tech companies, for example, Syngenta, Genus, Aviagen, JCB, New Holland and Velcourt among others. These companies finance the development of digital agricultural solutions that are used together with the agricultural machinery they manufacture.

It should also be noted that there is state-provided expenditure on agricultural research and development in the digital solutions space. The Government of the United Kingdom spent £450 million in 2011/12 on agri-food research and development (R&D). In the same year, it secured a further £160 million in this strategy to accelerate innovation by UK food and farming businesses and to drive UK growth through the emerging global markets. While the fractions of these expenditures that are dedicated to digital agricultural solutions remain largely unclear, the sizable numbers of these expenditures reveal the presence of funding for digital agricultural solutions for the region.[27]

Revenue sources for digital solutions: Due to the significantly large size of farming operations in the United Kingdom, there is a large incentive to pay for digital agriculture solutions for farmers in the region. This is because of the cost reduction potential of digital agricultural solutions in the region that comes with the application of these solutions to large-scale farming operations. In addition, as with several other regions that have several large-scale farming operations, the sale of agricultural machinery is also bundled with digital agriculture solutions in many cases. This hence means that revenue for developed solutions is also obtained indirectly from the sale of agriculture machinery like tractors, combine harvesters and soil sensors.

6.3.4 Enabling environment for digitalisation of agriculture in Europe

Technology enablers

1. Internet penetration rates: Internet penetration in Commonwealth Europe is comparatively higher than in other Commonwealth regions. The proportion of people using the internet in the region is shown below.

Table 6.2: Individuals using the internet (% of population)

|

Individuals using the internet (% of population) |

|

|

Cyprus |

86 |

|

Malta |

86 |

|

United Kingdom |

93 |

Source: Author computations from the World Bank indicator database.[28]

The drivers of high internet penetration and connectivity are presented as follows:

Presence of sub-marine and terrestrial cabling that provides consistent connectivity. The United Kingdom has one of the highest numbers of submarine cable connections, with more than 65 cable landing stations, and over 400 sub-marine cables that link the country to major routing hubs in the United States and Europe. Cyprus and Malta have 4 and 5 submarine cable landing stations respectively. The countries each have more than 4 sub-marine connections. This puts them at an advantage in case of any disruptions such as climate shocks compared to other island countries for example those in the Caribbean region.

Roll-out of 5G. Noteworthy is the fact that several mobile operators in the United Kingdom firmly embraced 5G technology in 2019 and rolled out deployments in major cities across the nation. While the 5G experience varies by operator, its roll-out by major network operators in the country is expected to greatly enhance upload and download speeds, which will in turn improve the consumption in internet services as more consumers make the shift from 4G to 5G.

2. Mobile penetration

Table 6.3: Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people)

|

Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people) |

|

|

Cyprus |

144 |

|

Malta |

144 |

|

United Kingdom |

120 |

Source: Author computations from the World Bank indicator database.[29]

Mobile penetration rates in Commonwealth Europe are high as compared to other Commonwealth regions. While there is insufficient documentation, the penetration of smartphones in the countries of Malta, Cyprus, and the United Kingdom is noted as having one of the highest smartphone penetration rates in the world[30]i.e., an estimated 83 per cent of the adult population in the United Kingdom are smartphone subscribers. Additionally, about 65 per cent of the households in all the European Commonwealth countries had at least one personal computer by 2016.[31]

Non-technology enablers

1. Sizes of agricultural land: As seen in locations with similarly large commercial farming arrangements, farm sizes with large land areas were ideal for smart farming methods in order to recoup return on investment, through more effective application of agricultural inputs like water, pesticides and fertilisers at scale.[32]

2. High literacy rates: The education levels of farmers in Commonwealth Europe are considerably high. At least one-third have pursued and obtained qualifications for courses or higher education in agriculture or related subjects. This share is also higher than the total share of farm managers with at least basic agricultural training in Malta (31 per cent). In Cyprus, 28 per cent of the total farm managers attained basic or full agricultural training by 2016. Farmers with such high levels of education have a better understanding of the benefits of digital technologies farming solutions and are hence more likely to invest in them.[33]

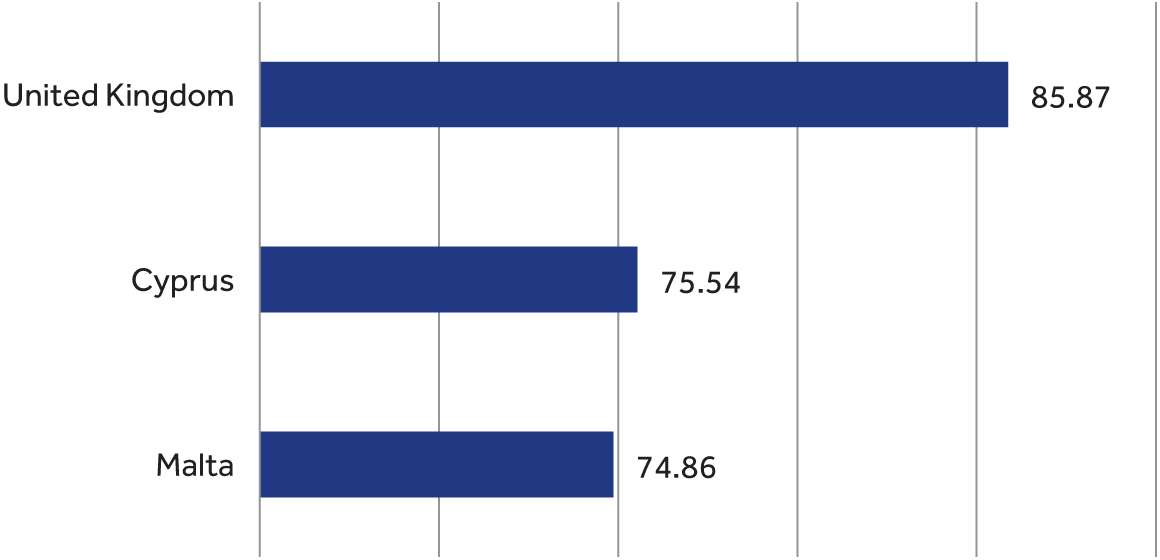

3. Large-scale monoculture (growing one crop) as opposed to inter-cropping more than one crop on the same plot of land: As is the case in Australia and New Zealand, aerial imagery thrives in the United Kingdom because monoculture is practiced on a large scale. Utilisation of aerial imagery is hard when more than one crop is grown on the same piece of land. Overall, this section compares the GSMA mobile connectivity indices of European Commonwealth countries. All the assessed countries had index scores of more than 60. The score reveals a more enabling environment for digitalisation in the European, Commonwealth Countries.[34] As compared to those in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

This index has been detailed in the annex.

Figure 6.6: GSMA Mobile Connectivity Indices for European Commonwealth countries (2019)[35]

6.4 Lessons from digitalisation of agriculture in Commonwealth Europe

Robust regulation regarding the use of farmer data in digital agricultural solutions: Many digital agricultural solutions worlds overuse various forms of farmer data to create their value propositions. In many of these jurisdictions, however, these digital solutions are not regulated regarding the use and dissemination of farmer identifier data. The European Union member Countries, which are also part of the Commonwealth (Cyrus and Malta), have robust regulations that protect their privacy and the non-consensual use of their data in the development of digital agriculture data products.

The active role of the private sector in facilitating data-driven smart farming: In the United Kingdom, the development of digital agriculture solutions in the country is financed by the research and development budgets of large agriculture corporations like Syngenta, Genus, Aviagen and agriculture equipment manufacturers like New Holland. This insight could inform the digital agriculture strategies in areas that do not have a significant presence of such large entities. These could choose to either attract these entities or substitute their presence with significant digital agriculture research.

The state enabled the roll-out of 5G networks in the region: In the United Kingdom, the has been a significant roll-out of 5G networks. While these are yet to be used directly in the digital agriculture space, they present a significant opportunity when their use is viewed from the smart farming dimension. Other Governments can also form public-private partnerships with the mobile network operators to ensure that in the future, the full capacity of IoT applications in the agricultural space can be better facilitated by 5G coverage.

Island countries can learn from the UK model of leveraging public–private partnerships to increase available connectivity bandwidth: The United Kingdom has in many cases shared the cost of construction and maintenance of international submarine cables with public–private partnerships. Small island countries in the Caribbean and Pacific islands could use a similar model to deal with the existent coverage gaps on the islands and enhance access to affordable international connections.

Having farms operates as business entities drives up digital solution uptake: Most of the farming operations in the United Kingdom are operated and registered as business entities. This means they have the incentive to use smart farming since it presents a vast opportunity to cut costs in the application of farming inputs, through better monitoring and tracking of the farm production processes. This can inform the digital agriculture strategy of many Commonwealth countries that have mainly subsistence farming operations, with large smallholder farmers. For many of these countries, the strategy would significantly involve capacity building of the farming entities to consume digital agricultural solutions, first by transforming them from being smallholder subsistence farmers to commercial farming entities.

Digital Agriculture report homepage Conclusion Back to top ⬆

[1] Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, FAOSTAT. Data retrieved on August 8, 2021. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

[2] Eurostat (2012). Agriculture Census in Cyprus. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Archive:Agricultural_census_in_Cyprus&oldid=347641

[3] Eurostat, Agriculture Census in Malta. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Archive:Agricultural_census_in_Malta&oldid=379558

[4] Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2019). Census of agriculture in the UK 2019 Report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/950618/AUK-2019-07jan21.pdf

[5] Chen, C. and I. Noble and J. Hellmann (2015). University of Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index. https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/matrix/

[6] Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2016). Agricultural labour in England and the UK Farm Structure Survey 2016.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/771494/FSS2013-labour-statsnotice-17jan19.pdf

[7] Shields, R. (2018). Women are a growing force in British farming. https://www.agrirs.co.uk/blog/2018/07/women-are-a-growing-force-in-british-farming

[8] Agerholm, H. (2019). Men have always taken the glory: Why more women are becoming farmers. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-49322620

[9] https://maltacvs.org/voluntary/malta-youth-in-agriculture-foundation/ (Accessed on the 14th July 2021).

[10] KPMG (2020). Agriculture sector, Sector trends & current challenges. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/cy/pdf/2020/08/sectoral-developments-and-covid-19-agriculture.pdf

[11] Practical Law Agriculture & Rural Land (2020). COVID-19: agriculture and rural land implications. https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-025-2984?originationContext=document&transitionType=DocumentItem&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true

[12] Wojciechowski, J. (2020). CORONAVIRUS: Emergency response to support the agriculture and food sectors. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/factsheet-covid19-agriculture-food-sectors_en.pdf

[13] Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2020). ‘Bounce back’ plan for agriculture, food and drink industry launched. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/bounce-back-plan-for-agriculture-food-and-drink-industry-launched

[14] Adkins, F. (2020). The fruitless saga of the UK’s ‘Pick for Britain’ scheme. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/11/19/pick-for-britain-a-rather-fruitless

[15] https://www.feedthenation.co.uk/

[16] Norris, J. (2015). Precision Agriculture: Separating the wheat from the chaff. https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/precision-agriculture-separating-the-wheat-from-the-chaff/

[17] https://www.xarvio.com/gb/en/products/field-manager.html (accessed on 14th July 2021).

[18] Agerholm, H. (2019). ‘Men have always taken the glory’: Why more women are becoming farmers. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-49322620

[19] https://croprotect.com/ (accessed on July 14, 2021).

[20] The UK Flood Information Service (2021). River and sea levels in England. https://flood-warning-information.service.gov.uk/river-and-sea-levels

[21] DroneDeploy (2020). Feel Good Friday: How Scientists Are Using Drone Technology to Monitor Ice Caps. https://www.dronedeploy.com/blog/how-scientists-are-using-drone-technology-to-monitor-icecaps/

[22] https://app.agrimetrics.co.uk/catalog/data-sets/f98daefb-f1c4-4f2f-aad5-c566e8695c49/overview

[23] Warren, M.F. (2002). Adoption of ICT in agricultural management in the United Kingdom: The intra rural digital divide. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286271893_Adoption_of_ICT_in_agricultural_management_in_the_United_Kingdom_The_intra-rural_digital_divide

[24] Department for Business, Innovation & Skill (2013). Industrial Strategy: Government and industry partnership, a UK strategy for Agricultural Technologies. https://www.gov.uk/Government/collections/industrial-strategy-Government-and-industry-in-partnership

[25] Butler, A. and M. Winter (2008). Agricultural Land Tenure in England and Wales. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6671412.pdf

[26] Barnes, A., I. Soto and Eory, et al. (2019). ‘Exploring the adoption of precision agricultural technologies: A cross regional study of EU farmers’. Land Use Policy 80, 163–174. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264837717315387

[27] Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (2013). A UK Strategy for Agricultural Technologies. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/227259/9643-BIS-UK_Agri_Tech_Strategy_Accessible.pdf

[28] Author computations from the World Bank indicator database.

[29] Author computations from the World Bank indicator database.

[30] internetNz (2017). State of the Internet in New Zealand. https://internetnz.nz/assets/Archives/State-of-the-Internet-2017.pdf

[31] New Zoo (2019). The Global mobile market report. https://newzoo.com/insights/trend-reports/newzoo-global-mobile-market-report-2019-light-version/

[32] Mehrabi, Z., et al. (2021). The global divide in data-driven farming. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-020-00631-0

[33] https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/ (accessed on July 14, 2021).

[34] Global System for Mobile Communications (2020). Mobile Connectivity Index (Methodology).

[35] The GSMA index is a quantitative score running from 0 (environment is least enabling) to 100 (environment is most enabling).

Digital Agriculture report homepage Conclusion Back to top ⬆