6.0 Commonwealth Europe

6.1 Fisheries profile in Europe

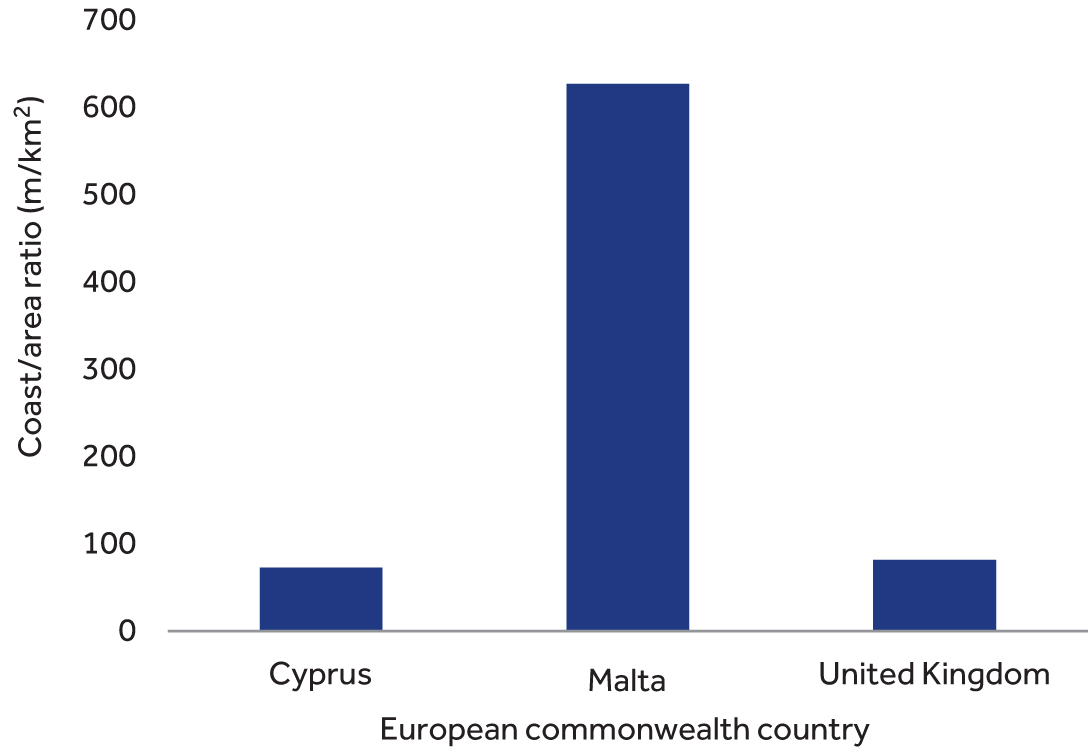

Europe’s capture fisheries produce 4.86 Mt annually (Table 6.1). The European Commonwealth is made up of the United Kingdom, Cyprus and Malta, each with high coastline to land area ratios, highlighting the important presence of maritime domains for these countries (Figures 6.1 and 6.2).

Table 6.1: Europe’s fishery profile

|

|

Sector |

Statistic |

|

Total annual production |

Capture fisheries |

4.86 million tonnes |

|

Inland fisheries |

0.41 million tonnes |

|

|

Aquaculture |

3,082.6 million tonnes |

|

|

Sources |

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/science-update/state-and-trends-eu-and-global-fisheries-and-aquaculture | http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/ca9229en.pdf | http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/ca9229en.pdf |

|

|

Contribution to GDP |

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP): European Union |

1.707 |

|

Sources |

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.AGR.TOTL.ZS?locations=EU |

|

|

Employment |

Fisheries |

272,000 |

|

Aquaculture |

129,000 |

|

|

Sources |

||

|

|

Per capita food fish consumption |

21.6 (kg/year) |

|

|

Sources |

Figure 6.1: Map of Europe showing Commonwealth countries.

Figure 6.2: Coastline to land area ratio for European Commonwealth countries.

In some instances, this ratio can be used as a useful indicator for a country’s reliance on fisheries resources.

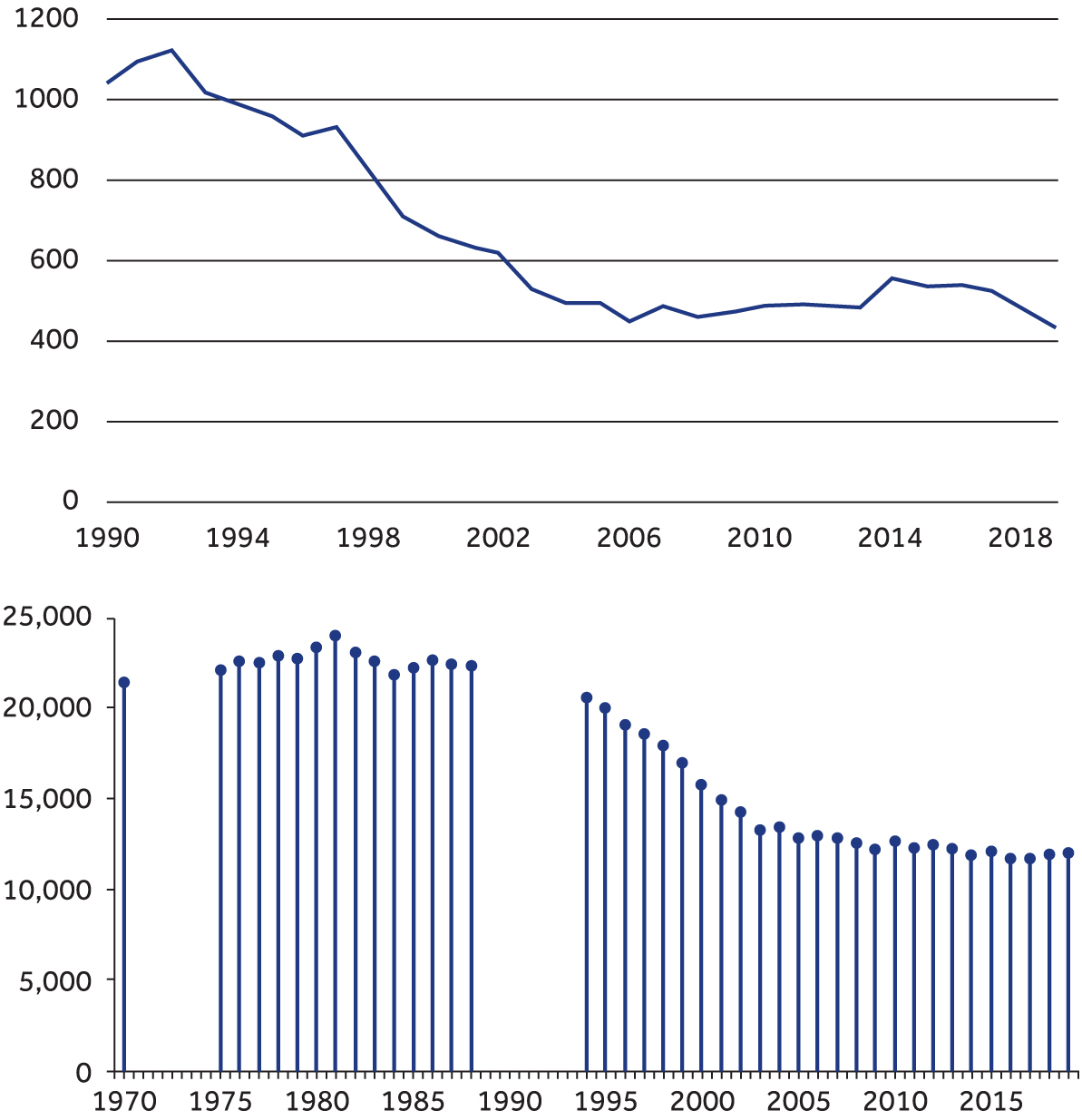

Fisheries within European Commonwealth states are as diverse as fishery operations in the other Commonwealth region The United Kingdom is considered one of the major fisheries and aquaculture nations in Europe landing 12 per cent of the total fisheries biomass in the EU.[1] In 2019, UK vessels landed 622 thousand tonnes of sea fish into the United Kingdom and abroad with a value of $1.3 billion USD.[2] [3] The total number of fishers employed in UK fishing in the same year was approximately 12,000 (45 per cent in England, 40 per cent in Scotland, 7 per cent in Northern Ireland and 7 per cent in Wales). It is noteworthy, however, that the United Kingdom’s economic output from fishing and aquaculture has decreased considerable since the early 1990s (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3: Fishing and aquaculture economic output 1990-2019.

£ million, real terms, 2018 prices (top) Number of fishers in the UK, 1970-2019 (bottom)

Source: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN02788/SN02788.pdf [accessed 29/09/2021]

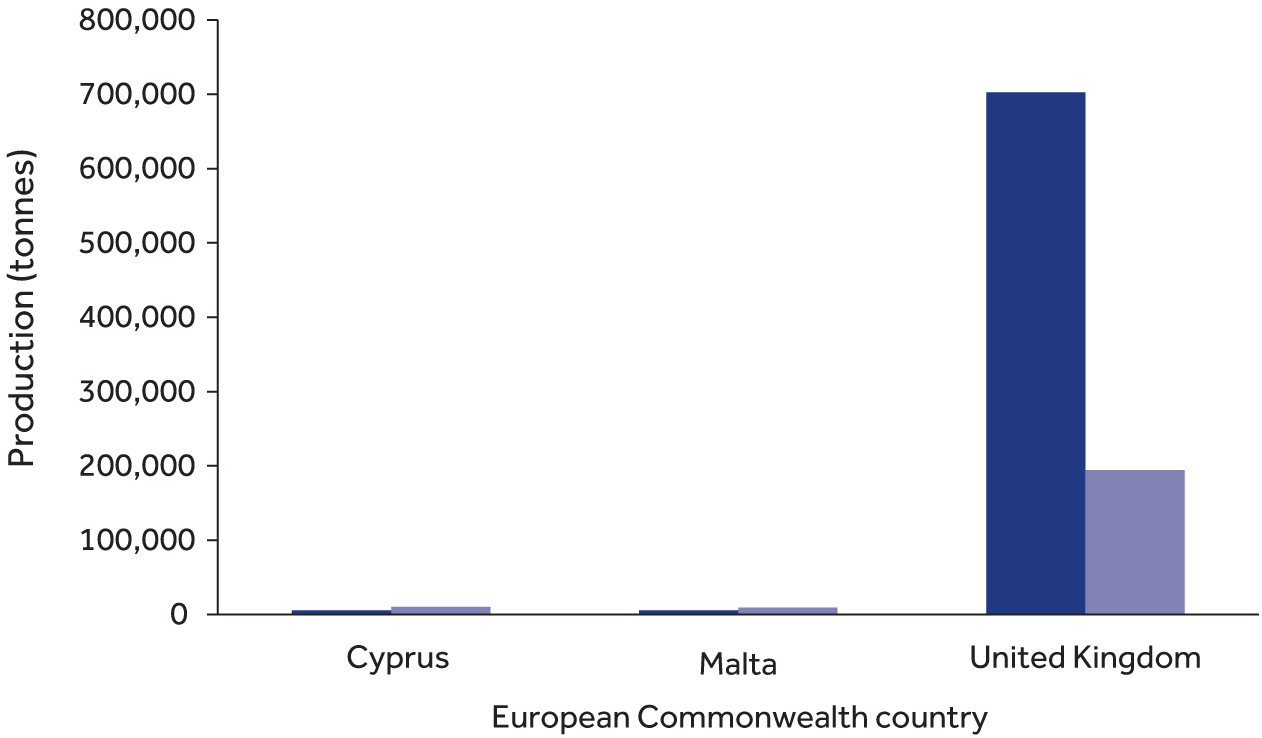

The fisheries sector in Cyprus plays a minor role in the overall economy of the country and is mostly conducted by SSF vessels under 12 m in length. Total capture production in 2019 was 1,480 tonnes of fish,[4] a fraction of the United Kingdom’s total capture (Figures 6.3 and 6.4). However, unlike the United Kingdom, Cyprus’ fisheries mainly provide the tourism industry with seafood and recreational activities.[5] The Maltese fleet, similarly, consists largely of SSF vessels, with 88 per cent of the fleet being less than 10 m in length. Total capture fisheries in Malta have been increasing since 2007, with a total capture in 2019 of 2,229 tonnes.[6] Both the Cypriot fisheries sector and the Maltese fisheries sector are some of the smallest in Europe (of the maritime nations) and are typical of other fisheries within the Mediterranean and are characterised as multi-species multi-gear operations.

Figure 6.4: Capture fisheries and aquaculture production for the European Commonwealth countries.

Deep Blue bars = fisheries, Light Blue bars = aquaculture. Source: WorldBank (2018-2019).

6.2 Digitalisation in European fisheries

6.2.1 United Kingdom

Like many national fishing industries, the UK industry is currently trying to rebuild sales following closures and supply chain problems forced by COVID-19. The country’s seafood sector is also coming to terms with changes following their departure from the EU (“Brexit”). Although there is keen interest in the benefits of digitalisation within the sector, few UK fisheries stakeholders are currently benefitting from advancements in digitalisation efforts.

6.2.2 Mediterranean

Due to the limited information pertaining to Cyprus and Malta individually, they are being discussed as part of the wider fisheries of the Mediterranean basin. SSF within the Mediterranean represent 83 per cent of the fleet, 57 per cent of employment onboard vessels, 29 per cent of revenue and 15 per cent of catch.[7] Digitalisation within these fisheries is generally obstructed by poor data availability within the sector, which often prevents them from being considered in centralised decision-making processes.[8] The sector is also considered highly vulnerable, with little access to financial services, which hinders their ability to modernise the fleet and recover from adverse events impacting their fisheries, particularly the SSF sector.[9]

6.3 Pillar 1: Digital innovations in European fisheries

6.3.1 United Kingdom: Digital technologies and digital solutions and services

The uptake of digital innovations within the United Kingdom’s fisheries sector is slow, but there is some progress being witnessed. Currently, digital innovations, such as in-water gear selectivity and real-time reporting apps, are already playing an increasingly critical role in the industry.[10] Collaborative agencies, such as Fisheries Innovation Scotland, have work ongoing to predict what digital tools are required to ensure sustainable and prosperous fisheries in the future, and how Scottish vessels can progress to this level of digitalisation.[11] The project aims to explore how digitalisation can add value to catches and build efficiencies in the supply chain, while simultaneously contributing to scientific data collection and sustainable practices.[12] The digital solutions that are available within the sector are relatively accessible; however, the value of these solutions is not currently well understood by the industry.

Digital innovations currently being used within the sector reflect the move towards digitising sales seen elsewhere in the world. “Pesky Fish”, an online marketplace established in 2017, offers a solution to connect UK fishers directly with wholesalers, restaurants and home chefs.[13] Pesky fish allows customers to buy fish directly from the United Kingdom’s inshore fishers as soon as it is landed for delivery anywhere in the United Kingdom the following day. Through cutting out the middlemen, Pesky Fish enables fishers and producers to receive a fairer price for their catch, whilst optimising traceability for consumers. Pesky Fish ensures that the supply chain they created between customers and fishers is 100 per cent transparent and hence, customers know who caught each fish, how it was caught and when it was landed. Furthermore, they promote sustainability by only working with fishers who use sustainable catch methods.[14]

Unlike other regions in the Commonwealth (Africa and SIDS), the United Kingdom’s digitalisation journey does not suffer from illiteracy or network connectivity. Most hurdles facing digitalisation within the sector are from pushbacks from the industry. For example, in 2018, England’s “Marine Management Organisation” announced the start of consultations on the introduction of catch recording for the under-10 m fleet.[15] However, this along with making VMS mandatory in the SSF fleet has been met with criticism from the industry, who states that introducing catch recording replicates extant data capture efforts and adds to workloads at sea, whilst adding VMS to SSF vessels would affect the sector through the cost of installing VMS (and downtime costs), privacy regarding access and use of data, operational issues such as running VMS on vessels with low/no power, and general discrimination against the fishing industry.[16] For digitalisation to be effective within the United Kingdom’s fisheries industry, efforts must be supported by those who work within the sector and must move away from this top-down control model.

6.3.2 Mediterranean: Digital technologies and digital solutions and services

The level of digital innovations within the Mediterranean’s fisheries is considered “low”, with little technology or research and development currently happening within the sector.[17] The Mediterranean’s fisheries sector is aging, which likely limits the scope for digital innovation and uptake of new technologies moving forward. In Malta, a 2020 study that focused on SSF found that the age cohorts of fishers interviewed were as follows: 2 per cent of fishers were under the age of 35, 9 per cent were between 35 and 45 years, 35 per cent belonged to the 45–55 age group, 31 per cent belonged to the 55–65 age group and the remaining 24 per cent belonged to the over 65 group. This distribution highlights the ageing demographics within the fisheries sector – a “greying of the fleet” – and the lack of recruitment to the industry among the younger generation.[18] Efforts to integrate digitalisation into the sector may attract a younger generation to the fisheries industry, as has been witnessed in the agriculture sector.[19]

The traditional nature of the fisheries sector in Malta and Cyprus is also hindering digitalisation efforts. Many fishers still fish using wooden-hulled vessels that require considerable maintenance to upkeep. Despite a switch to fibre-glass boats being more economically efficient, there is a reluctance within the sector to change due to the traditional aspects, as many vessels have been passed down through multiple generations. Almost 50 per cent of vessels in Malta are estimated to be over 40 years old.[20]

Fisheries digitalisation efforts in the catch sector are limited in Cyprus and Malta, and the Mediterranean fisheries sector in general. However, “The Quick Fish Guide” – a seafood consumer-facing tool has recently been produced by “Fish for Tomorrow”, with support from “European funding for youth”.[21] The aim of the guide is to provide information on the sustainability of locally caught and consumed fish species. The guide, which is updated every 2 years, presents fish along with a rating based on health of fish stocks, fishing methods and its consequences, social consequences, and any other environmental impacts of fishing, farming and importation to aid consumers in making sustainable choices.[22]

The use of remote sensing technologies to inform fisheries monitoring and management has great potential in the Mediterranean region considering many vessels do not benefit from vessel tracking technologies. A 2020 study utilised freely available data from the European Space Agency’s satellite, Sentinel-1, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) to detect migrant vessels in the Cyprus region. The results of this study found that Sentinel-1 SAR data can be used to provide decision makers with spatial information on vessel migration routes.[23] Although the study focused on the use of vessel monitoring for detecting unauthorised migrant vessels for search and rescue operations, there is great potential for this technology to be utilised to address IUU fisheries within the region.[24] Facilitating digitalisation within the sector will require addressing the adoption and implementation constraints, particularly regarding the exclusion of SSF from much of the ongoing modernisation work within the Mediterranean fleets.

6.4 Pillar 2: Data infrastructure in European fisheries

6.4.1 United Kingdom

The United Kingdom’s fisheries data is inconsistent in terms of quality and harmonisation. Although there are many diverse data sets being collected within the sector, much of this data is stored in silos for single-use purposes, which hinders the development as the industry is not able to benefit from the wider use and integration of the country’s fisheries data. Fisheries data is collected by the devolved governments of the countries within the United Kingdom as well as by public bodies, such as “Seafish”. The devolved governments of the United Kingdom generally vary in terms of data collection and utilisation, and there is still a distinct lack of centralised, harmonised data for the United Kingdom. There is also limited data sharing between each devolved government despite their fleets fishing the same waters. The success of the Seafish public body data collection centres on their collection and analysis of fisheries economic performance data within the United Kingdom, which they harmonise and merge with fleet numbers, landing figures and employment from government collected statistics.[25]

As is witnessed in fisheries sectors globally, the United Kingdom’s SSF sector is poorly understood in comparison to the United Kingdom’s large-scale operations. However, there are ongoing efforts to improve knowledge regarding SSF within the United Kingdom, such as Seafish’s “Future of our Inshore Fisheries” programme.[26] To prevent the availability of quality data from hindering digitalisation, the UK sector would greatly benefit from more automated recording of positional data in the SSF who make up the majority of the United Kingdom’s inshore fishing fleet. Currently, vessels over 12 m in length are mandated to use VMS systems.[27] There is, however, in some fleet segments continued pushback from the industry regarding the implementation of tracking systems (iVMS (inshore VMS)) onboard vessels <12 m in length.

6.4.2 Mediterranean

Fisheries data from the Mediterranean is fragmented. Although the EU requires vessels over 12 m in length to utilise VMS systems and electronic logbooks, while vessels over 18 m in length must also use AIS to monitor catches and fishing activities,[28] electronic reporting systems are not compulsory for SSF. Similarly, satellite-based VMS is compulsory for vessels greater than 12 m in length. Although not mandatory based on EU legislation, some countries within the Mediterranean do collect SSF data. Of all contracting and cooperating non-contracted parties associated with the General Fisheries Commission of the Mediterranean (GFCM), only 50 per cent require SSF vessels to report all landings at designated landing ports, while 35 per cent require some level of reporting, and 15 per cent require no reporting. Forty per cent require SSF vessels to report all landings through self-reporting tools, while 25 per cent require some landings to be reported through these means and 35 per cent do not require landings to be self-reported.[29]

Although not compulsory according to EU legislation, Malta collects data on vessels under 10 m in length as part of its Catch and Effort Assessment Survey (CAS).[30] Meanwhile in Cyprus, the use of VMS has been applicable to all professional fishing vessels of less than 15 m in length that hold an A or a B Category licence since 2010.[31] Vessels with license A or B, which are mostly <12 m in length, are allowed to operate every day all year round, with a number of restriction measures on the use of fishing gears and minimum landing sizes, according to the national and community law.[32]

6.5 Pillar 3: Business development services in European fisheries

6.5.1 United Kingdom

Business development within the United Kingdom’s fisheries sector has been heavily impacted by their departure from the EU due to changes in export requirements. In response to this, the UK government announced in January 2021 that they are offering funding of up to $31 million USD to support fishing export businesses who can prove they suffered from financial losses in exporting fish and shellfish to the EU due to Brexit and/or COVID-19. The fund is targeting small and medium enterprises, with the maximum claim available to individual operators set at $137,000 USD. In addition to funding, the UK government is offering support to businesses in adapting to new export processes, including training packages and focused workshop sessions.[33]

The UK fishing and seafood sector is also set to benefit from additional government investment worth a £100 million fund to help modernise fishing fleet, modernise the fish processing industry and rejuvenate “a historic and proud industry in the United Kingdom” on top of the funding that will replace the lost EU funding in 2021.[34]

Although such emergency and developmental funding is directed at supporting the fishing industry, there are few mentions of innovation or digitalisation within the UK fisheries sector. One important programme that was run between 2019 and 2021 was the Seafood Innovation Fund led by the Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquaculture. The $13.7 million USD fund was designed to deliver cutting edge technology and innovation by supporting ambitious projects with a long-term view.[35] The fund has now closed, but already some exciting developments are on the way involving innovations for sustainable seafood production, reducing commercial risk and strengthening sustainable fisheries management. Such funds will be crucial to the United Kingdom’s fishing sector in coming years following the double shock of COVID and Brexit. However, one may argue that the size of the funds is not especially significant nor does an early injection of capital necessarily spell success if projects are unable to raise their own second-round funding or if they lack self-perpetuating funding models.

6.5.2 Mediterranean

There are ongoing efforts to support and fund digital solutions within the Mediterranean’s fisheries sector. For example, STARFISH 4.0 is an EU-funded 2-year project running throughout 2020 and 2021 proposing new technologies for the safety of SSF and sustainable marine resource management.[36] The project aims to diversify SSF by increasing their opportunity to fish for higher value species further offshore while ensuring traceability to improve the marketability of landings.[37] The project also aims to empower local SSF by giving them the opportunity to better engage with the management of marine protected areas. STARFISH also actively supports digital transformation within the sector. This involves the use of the “NEMO system”, which is a solar-powered VMS system with call for assistance button as well as monitoring software with Big Data capability.[38]

Financial support is also offered to European fisheries through the “European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF)”.[39] The fund is due to run from 2021 to 2027 and has a total a budget of €6.108 billion. The EMFAF offers support for developing innovative projects ensuring that aquatic and maritime resources are used sustainably. It aims to facilitate the socio-economic attractiveness and the generational renewal of the fishing sector, in particular with regards to small-scale coastal fisheries, the improvement of skills and working conditions in the fishing and aquaculture sectors, the economic and social vitality of coastal communities and innovation in the sustainable blue economy among others.[40] Such work within the sector develops the foundations essential for digitalisation efforts.

There is also considerable NGO involvement in improving the sustainability of the Mediterranean’s fisheries. Although NGO engagement in general in the Mediterranean is high with significant investment from large NGOs/INGOs like Oceana, WWF and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, specific cases relating to digitalisation are somewhat lacking. Although not focused on digitalisation, the Blue Marine Foundation is working in Cyprus to implement a locally adapted co-management plan that will result in a substantial cohort of local fishers leading the way in sustainability through active engagement in marine management.[41] Such engagement is a promising step for SSF communities in the European Commonwealth although future investments in digitalisation from NGOs is largely unknown other than Malta’s NGO-led “Quick fish guide”. Encouraging fishers to take an active role in managing the marine environment can improve engagement with wider initiatives in the future, which will hopefully aid with digitalisation efforts if appropriate funding streams are available.

6.6 The base: Enabling environment for digitalisation in European fisheries

6.6.1 United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has one of the most promising enabling environments in the Commonwealth with good infrastructure, educational levels and data collection. However, digitalisation still appears to be slow. This is surprising when considering the self-evaluative nature of the UK fisheries industry. For example, although the industry is well aware of it generally poor safety record (considering its “developed” status), there seems to be little movement in the space surrounding the role of digitalisation and safety.[42]

Similar to Canada, many believe that the COVID-19 pandemic can pave the way to new model for UK fisheries, particularly in light of Brexit.[43] Some industry and government departments are slowly beginning to put digitalisation on the agenda, but digitalisation will most likely be introduced unevenly with large players investing and smaller companies not having the foresight or resources to keep up. There is a key role for governments in setting out clear strategies so that the benefits of digitalisation will be evenly spread across the UK seafood sector.

In November 2020, the United Kingdom’s new fisheries policy, The Fisheries Act 2020 entered into force, giving the United Kingdom “full control” of their fishing waters out to 200 nautical miles, for the first time since 1973, following their departure from the European Union.[44] Underpinning the Act is a commitment to sustainability and protecting the seas for future generations of fishers. To satisfy the Act, the UK government and devolved administrations must develop new fisheries management plans with the aim of benefiting the fishing industry and the environment. The introduction of a new Act and the reformation of the sector post Brexit offers a prime opportunity to advance digitalisation efforts. This should also focus on improving fisheries data sharing between the United Kingdom’s devolved administrations and taking a holistic approach to managing the United Kingdom’s fisheries.[45]

6.6.2 Mediterranean

The Mediterranean has a number of ongoing programmes supporting the “blue economy” (e.g., FAO/GFCM,[46] WestMED initiative,[47] Blue Med initiative,[48] LabMAF,[49] INTERREG MED BLUEfasma[50] and MedAID[51] to name a few). This concerted effort to improve the sustainability of fisheries and other maritime economies is promising, but the documentation around these projects lack any real mention of digitalisation. The enabling environment in Malta and Cyprus does not appear to be limited by connectivity or infrastructure issues but does seem to lack appropriate investments. Currently, the only real digitalisation observed is through NGO partners whose funding is finite and, some may argue, priorities are not always aligned with what is best for the sector economically (e.g., sustainability drive versus an economics drive). Government support for fisheries in Malta and Cyprus is primarily focused on non-digital approaches to enhancing productivity, and there appears to be little consideration of innovation in the digitalisation space.

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆

[1] The EU Fishing Fleet Is Getting Smaller (2020) https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20200130-2

[2] Marine Management Organisation (2019) UK Sea Fisheries Statistics 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/920679/UK_Sea_Fisheries_Statistics_2019_-_access_checked-002.pdf

[3] Ares, E., E. Uberoi, G. Hutton and M. Ward (2021) UK Fisheries Statistics.

[4] Statistics | Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/fish_ca_main/default/bar?lang=en

[5] FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Republic of Cyprus. Fisheries and Aquaculture - National Aquaculture Sector Overview - Cyprus (fao.org)

[6] Statistics | Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/fish_ca_main/default/bar?lang=en

[7] FAO (2020) The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2020. doi:10.4060/cb2429en.

[8] FAO (2020) The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2020. doi:10.4060/cb2429en.

[9] FAO (2020) The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2020. doi:10.4060/cb2429en.

[10] Hollely, B. ‘Fisheries Innovation Scotland announce new projects to help strengthen the Scottish seafood sector’. Fisheries Innovation Scotland. https://fiscot.org/2980-2/

[11] Hollely, B. (2021) ‘A Digitalisation Roadmap for Scotland’s Fisheries (FIS036)’. Fisheries Innovation Scotland. https://fiscot.org/fis-projects/a-digitalisation-roadmap-for-scotlands-fisheries-fis036/

[12] Hollely, B. ‘Fisheries Innovation Scotland announce new projects to help strengthen the Scottish seafood sector’. Fisheries Innovation Scotland. https://fiscot.org/2980-2/

[13] Cumming, E. (2021) ‘From the Docks to the eBay – Will Online Marketplaces Save The Fishing Industry?’ The Observer.

[14] Home. Pesky Fish. https://peskyfish.co.uk/

[15] New Catch-Recording Requirements Explained – Marine Developments (2018) https://marinedevelopments.blog.gov.uk/2018/11/29/catch-recording-app-fishing/

[16] Summary of Responses (2019) GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/introducing-inshore-vessel-monitoring-systems-i-vms-for-fishing-boats-under-12m/outcome/summary-of-responses

[17] Almendro, R., S. Klarwein and L. Segura (2020) Blue Solidarity Economy in Catalonia, Europe and the Mediterranean. 37–57. https://medblueconomyplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/file-library-6f7b2cfaa8402e86d673.pdf

[18] Cavallé, M., A. Said, I. Peri and M. Molina (2020) Social and Economic Aspects of Mediterranean Small-Scale Fisheries: A Snapshot of Three Fishing Communities. https://lifeplatform.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/LIFE-Social-and-Economic-Aspects-of-Mediterranean-SSF-compressed.pdf

[19] European Commission. Digital Transformation in Agriculture and Rural Areas. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/factsheet-agri-digital-transformation_en.pdf

[20] Cavallé, M., A. Said, I. Peri and M. Molina (2020) Social and Economic Aspects of Mediterranean Small-Scale Fisheries: A Snapshot of Three Fishing Communities. https://lifeplatform.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/LIFE-Social-and-Economic-Aspects-of-Mediterranean-SSF-compressed.pdf

[21] Penca, J. Said, A., Cavalle, M., Libralato, S., Pita, C. (2020) Market Opportunities for Artisanal and Small-Scale Fisheries Products for Sustainability of the Mediterranean Sea Towards an Innovative Labelling Scheme. Euro-Mediterranean University.

[22] Quickfish Guide – Fish for Tomorrow. https://www.fishfortomorrow.com/quickfish-guide

[23] Melillos, G. G., Themistocleous, K., Danezis, C., Michaelides, S., Hasjimitsis, D.G., Jacobsen, S., and Tings, B. (2020) ‘Detecting migrant vessels in the cyprus region using sentinel-1 SAR data’. In Counterterrorism, Crime Fighting, Forensics, and Surveillance Technologies IV, vol. 11542. SPIE, 134–144.

[24] Cicuendez Perez, J., M. Alvarez Alvarez, J. Heikkonen, J. Guillen and T. Barbas (2013) ‘The Efficiency of Using Remote Sensing for Fisheries Enforcement: Application to the Mediterranean Bluefin Tuna Fishery’. Fisheries Research 147, 24–31.

[25] Fishing data and insight. Seafish. https://www.seafish.org/insight-and-research/fishing-data-and-insight/

[26] Future of Our Inshore Fisheries. Seafish. https://www.seafish.org/responsible-sourcing/fisheries-management/future-of-our-inshore-fisheries/

[27] Summary of Responses (2019) GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/introducing-inshore-vessel-monitoring-systems-i-vms-for-fishing-boats-under-12m/outcome/summary-of-responses

[28] Vessel Monitoring System (VMS+) Guidance. 3 (2019).

[29] FAO (2020) The State of Mediterranean and Black Sea Fisheries 2020. doi:10.4060/cb2429en

[30] Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture (2019) Malta’s Work Plan for data collection in the fisheries and aquaculture sectors 2019. https://datacollection.jrc.ec.europa.eu/documents/10213/1245809/MLT_WP_2019_text.pdf/909b2d3d-fc66-4385-aade-b49e49883341?version=1.0

[31] The current development of the fishing industry in Cyprus (2021) https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/current-development-fishing-industry-cyprus-zacharias-l-kapsis

[32] Department of Fisheries (2020) Cyprus Annual Report on Efforts During 2019 to Achieve a Sustainable Balance Between Fishing Capacity and Fishing Opportunities. https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/system/files/2020-09/2019-fleet-capacity-report-cyprus_en.pdf

[33] New Financial Support for the UK’s Fishing Businesses That export to the EU (2021) GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-financial-support-for-the-uks-fishing-businesses-that-export-to-the-eu

[34] New Financial Support for the UK’s Fishing Businesses That export to the EU (2021) GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-financial-support-for-the-uks-fishing-businesses-that-export-to-the-eu

[35] Seafood Innovation Fund – CEFAS (Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science). https://www.cefas.co.uk/impact/programmes/seafood-innovation-fund/

[36] STARFISH 4.0: EU Funds Innovative Digital Solutions for Supporting Small-Scale Fisheries in the Mediterranean (2021) https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/news/starfish-40-eu-funds-innovative-digital-solutions-supporting-small-scale-fisheries_en

[37] STARFISH 4.0: EU Funds Innovative Digital Solutions for Supporting Small-Scale Fisheries in the Mediterranean (2021) https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/news/starfish-40-eu-funds-innovative-digital-solutions-supporting-small-scale-fisheries_en

[38] STARFISH 4.0: EU Funds Innovative Digital Solutions for Supporting Small-Scale Fisheries in the Mediterranean (2021) https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/news/starfish-40-eu-funds-innovative-digital-solutions-supporting-small-scale-fisheries_en

[39] European Commission (2021) ‘European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF)’. https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/funding/emfaf_en

[40] European Commission (2021) ‘European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF)’. https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/funding/emfaf_en

[41] Mediterranean Small-Scale Fisheries. Blue Marine Foundation. https://www.bluemarinefoundation.com/projects/mediterranean-small-scale-fisheries/

[42] Fishing crews urged to turn the tide on industry’s safety record (2020) Seafish. https://www.seafish.org/about-us/news-blogs/fishing-crews-urged-to-turn-the-tide-on-industry-s-safety-record/

[43] Kemp, P.S., R. Froese and D. Pauly (2020) ‘COVID-19 provides an opportunity to advance a sustainable UK fisheries policy in a post-Brexit brave new world’. Marine Policy 120, 104114.

[44] Flagship Fisheries Bill Becomes Law (2020). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/flagship-fisheries-bill-becomes-law

[45] Flagship Fisheries Bill Becomes Law (2020). GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/flagship-fisheries-bill-becomes-law

[46] http://www.fao.org/gfcm/about/en/

[47] https://www.westmed-initiative.eu/

[48] http://www.bluemed-initiative.eu/

[50] https://bluefasma.interreg-med.eu/

[51] http://www.medaid-h2020.eu/

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆