7.0 Conclusions and recommendations

7.1 Regional comparisons

To make comparisons about the state of digital fisheries across the different Commonwealth regions, it is first important to highlight key divisions in fisheries that make broad region-to-region comparisons inaccurate and unhelpful:

- Fisheries can broadly be divided into SSF and LSF. There are several different definitions of SSF and LSF, but in general, it is important to understand that SSF often (unless in developed countries) suffer from a lack of funding (government and business and personal capital injection), use simple equipment on board and in many cases make short trips, close to shore and land seafood mainly for local consumption.

- Each of the Commonwealth regions has at least one country that is more developed (based on GDP) than others in the same region. This has an important bearing on comparisons between countries within the same region. For example, Commonwealth Pacific fisheries are quite different when comparing the SSF of Australia and New Zealand versus the Pacific SIDS.

It is therefore important that broad regional characterisations are not made about whole regions. Comparisons must account for differences in developmental status of a country and the difference between SSF and LSF. Table 7.1 provides general illustrative purposes only to highlight the four-dimensional complexity of any regional comparisons made.

Table 7.1: The 4-dimensional complexity of any regional comparisons made.

|

|

Low GDP |

High GDP |

|

SSF |

Undeveloped |

Undeveloped & developed |

|

LSF |

Undeveloped & developed |

Developed |

Examples to illustrate the four dimensions in Table 7.1:

- Low GDP country = Ghana. SSF are undeveloped. LSF (national) are undeveloped, but Ghana also has some LSF that are developed based on fishing agreements with foreign nations.

- High GDP country (compared to Ghana) = Malta. SSF are based on traditional methods and therefore largely undeveloped. Yet other SSF in the European Commonwealth (the United Kingdom) are considerably developed.

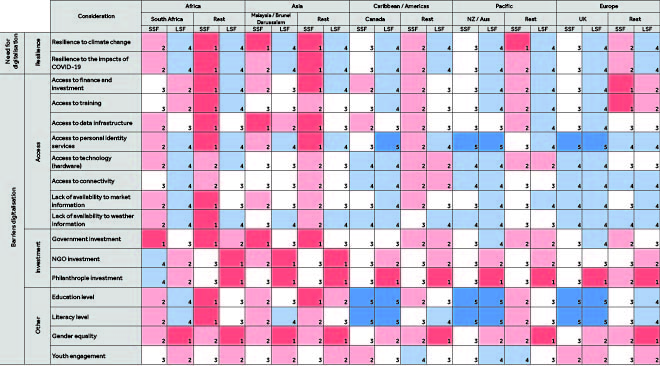

To try and standardise some sort of high-level comparison between the different Commonwealth regions, we created a matrix that accounts for the aforementioned divisions and lists a range of different needs and barriers to digitalisation (Table 7.2). Each intersect between a region (or country)/fishery sector is qualitatively scored 1–5 based on our understanding of the state-of-the-art from our literature review research and the KI interviews. All scores a relative. Cells with bold outlines are those for which we found it difficult to find good information. The idea of the matrix is to highlight patterns across the Commonwealth, and this is not meant to be a prescriptive or comprehensive analysis. It contains many educated guesses and would likely look slightly different with different experts if they were asked to fill the matrix.

Table 7.2: Matrix illustrating qualitative scoring for barriers to (and needs for) digitalisation in fisheries per region, accounting for inherent differences in small- and large- scale fleets and GDP within each region (low versus high).

1 = low (poor resilience, access, investment, other) 5 = high. Colours are on the same scale as the 1-5 scoring. Cells with thick black lines are those for which data / understanding was lacking and therefore an educated guess was made).

Key patterns across the Commonwealth:

- SSF in less-developed countries are generally the least resilient sector to climate change and the impacts of COVID.[1]

- SSF generally score less than LSF when considering barriers to digitalisation,[2] i.e., there are more barriers to digitalisation.

- Africa and Asia score the lowest (have the least conducive/enabling environments for fisheries digitalisation) overall followed by the Caribbean and the Americas, the Pacific and Europe.

- SSF and LSF scores follow the same pattern with low scores in Africa and Asia followed by the Caribbean and the Americas, the Pacific and Europe.

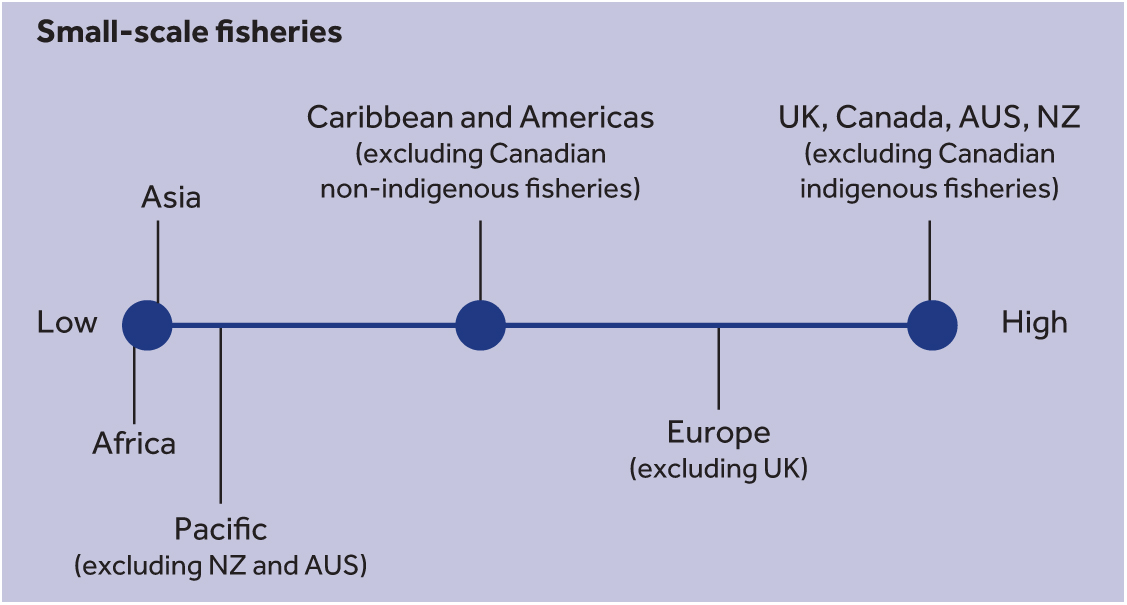

Based on the aforementioned qualitative analysis, KI interviews and our knowledge of the different regions, the most useful groupings to simplify comparisons between the diverse SSF is based on a development scale and is illustrated in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: Diagram illustrating the approximate (assumed) difference in developmental status of small-scale fisheries between the five Commonwealth regions.

The methods used to collect information for each of the regions come with their own pitfalls. The primary one being that the summaries of digitalisation may be missing information that was not uncovered through the literature review and KI interviews. Hence, the following summaries must be taken with caution and be used only as approximate generalisations.

- SSF in Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands.

- These fisheries are all limited by connectivity issues based on either a lack of infrastructure and/or mobile connections that are too expensive to warrant the use of innovations that rely on mobile technologies.

- Maritime weather information across the regions is generally poor which in combination with limited connectivity presents issues with technologies aiming to improve safety at sea.

- For Africa and Asia, the ability to form personal, digital identity is commonly lacking which subsequently limits enrolment in technologies that provide access to direct to consumer/market sales and personal financial transactions.

- The funding environment in the fisheries in these regions also lacks, largely having a limited scope (small and short period funding pots) and often lacking from investment from private enterprise. Funding is more common from NGO-type sources and outside philanthropy which is useful for the initial build of initiatives but often leads to a bottleneck longer term once platforms are up and running. This is where industry and government investment and incentive schemes may play an important role.

- SSF and LSF in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United Kingdom

- Many of these fisheries do not suffer from lacks in infrastructure or data capture.

- Limitations in these fisheries regarding digitalisation are often based around poor data harmonisation, communication between devolved administrations and a lack of government drive to actively promote digitalisation and collaboration with industry.

- Policy and regulatory environments in these fisheries will likely benefit from reform that allows better data sharing and collaborative use.

- SSF in the Caribbean appear to lie between the two aforementioned examples, with better investment and movement towards digitalisation in fisheries but with significant holes in data infrastructure and sharing.

- It is difficult to compare LSF from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean because there is little information available, and in many cases, these LSF are developed based on fishing agreements with external/ foreign operators.

7.2 Pioneering Digital Innovations for Fisheries

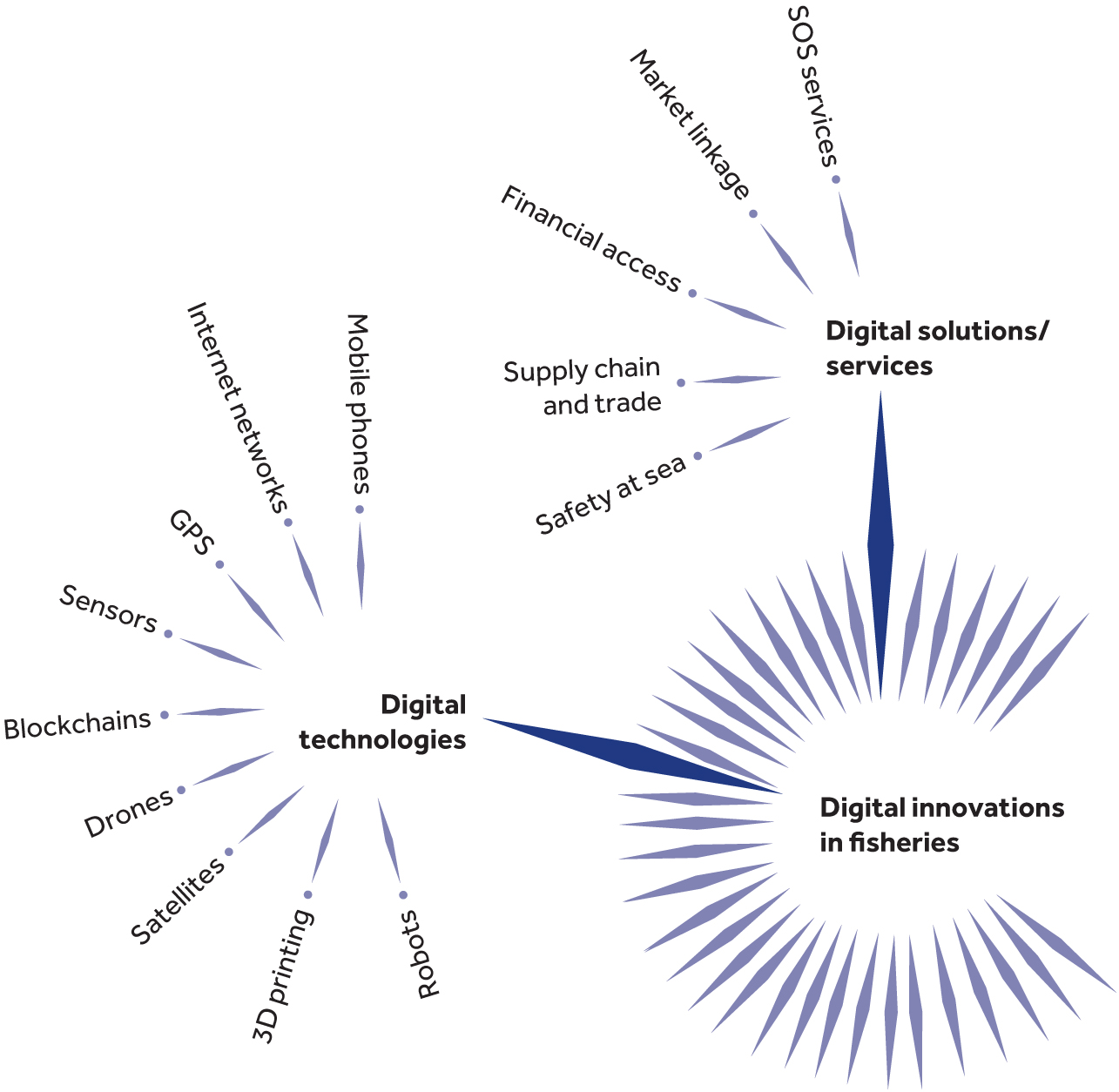

There are a huge number of potential digital innovations to improve fisheries sustainability and economic productivity across the Commonwealth region (Figure 7.2). Drawing on examples from the KI interviews from across all regions, we summarise what we consider to be pioneering innovations and where they would be most useful across all the regions – largely for the SSF sector in the less developed nations within each region (Tables 7.3 and 7.4). Note: For the aforementioned reasons regarding the differences between SSF and LSF, these innovations have different scope and worth in different regions and in different fishery sectors (SSF versus LSF).

Table 7.3: “Pioneering digital innovations” from within the fisheries of the Commonwealth.

|

Name of company / organisation / innovation |

Brief description |

Digital Solution / Service |

Digital Technologies |

Free to use? |

Africa |

Asia |

Caribbean / Americas |

Pacific |

Europe |

|

Digital & financial inclusion, transparent supply chains and increased market value through mobile phone application |

Financial access, market linkages, supply chain services |

Smartphones, QR codes |

No - Software As A Service (SaaS)

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mobile money platform that enables fishers to access formal financial services through the creation of a digital identity |

Financial access, personal identification |

Smartphone |

Yes |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Maritime broadband service, electronic catch documentation and traceability, and VMS |

Safety at sea, traceability, MCS |

Satellite technology, VMS antenna |

No – ‘cost conscious’ and flexible subscription packages |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Open-source tool for fish nutrients data |

Data sharing / accessibility |

Device for access |

Yes |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Blockchain based currency that allows users with a smartphone to use a mobile phone app to make payments via a QR code |

Financial access, |

Blockchain, smartphones, QR codes |

Yes – pay or transfer money, without fees, in real time |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

‘Fisheries Early Warning and Emergency Response’ system |

Safety at sea, MCS |

Smartphone |

Yes |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Online fish marketplace and delivery service |

Traceability, market linkage |

Smartphone |

Yes – free to download, but takes commission per sale |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Guide which provides consumers with information on the sustainability of locally caught and consumed fish species |

Data sharing / accessibility |

Device for access |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

X |

Table 7.4: Summary of what we believe are the top three, established key pioneering technologies and where they would be most useful across the 5 Commonwealth regions.

*denotes the ‘home’ region of the technology. Numbers refer to species notes that can be found below the table.

|

Pioneering technology |

Africa |

Asia |

Caribbean / Americas |

Pacific |

Europe |

|

ABALOBI |

X* |

X |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

FEWER |

X |

X |

X* |

X |

X |

|

D-Cash / MCash |

X |

3* |

X* |

X |

3 |

Figure 7.2: Summary of digital innovations in fisheries split into digital technologies and digital services.

- ABALOBI may not be entirely feasible in highly fragmented island states as it relies on good transport networks for the quick movement of seafood products from net to plate.

- ABALOBI would certainly be useful across Europe; however, a number of separate technologies already exist that somewhat fill the different niches across which ABALOBI stretches (e.g., direct to consumer market applications like PeskyFish (the United Kingdom), traceability and transparency apps like Verifact (multiple countries) and custom analytics like the Seafish annual economic performance reports (the United Kingdom), etc.)

- Cash transactions between individuals is less of an issue in Asia than it appears to be in SSF communities in other regions. The MCash app is like D-cash but specific to Sri Lanka only (at present).

7.3 Recommendations

There are myriad challenges and digital solutions that can be found for fisheries across the five Commonwealth regions. The applicability of different innovations/services is largely determined by the developmental status of the fisheries (which generally correlates to national GDP within regions) and the division between SSF and LSF.

Based on what we believe to be a good (but not fully comprehensive) coverage of the evidence for each region, The Commonwealth Secretariat can play the following roles in supporting digitalisation in the five regions.

Pillar 1: Digital Innovations

- Implement programmes in under-developed SSF contexts that create awareness around and incentivise digitalisation that does not necessarily rely on comprehensive mobile connectivity (e.g., low data apps or self-recording apps that can be downloaded post-event with better signal or hard wire downloaded to a centralised system).

- Promote collaborations between private business and government to bring innovation into under-developed fisheries contexts whilst helping governments harness such innovations and scale them up nationally.

- Provide governments with country-specific “state-of-the-art” reports on the state of digital technologies in their different fisheries sectors, highlighting key opportunities for development.

- In very under-developed cases, offer training and capacity building programmes for mobile phone and application use/literacy and use such pilots to “test the water” for future development of digitalisation.

Pillar 2: Data Infrastructure

- Support governments in data policy formation to facilitate data sharing and coordination between government and fishing related industries. This will help develop baseline data upon which good management as well as innovation rests.

- Provide government employees with training on database structure, application programming interface development and cloud-based server use.

- In very basic data settings, ensure governments are working to support personal identification. Personal identification is vital to help individuals eventually progress towards personal finance solutions as and when such technologies come online.

Pillar 3: Business development and investment

- Promote the formation of coherent groups (like cooperatives) that lie between the level of individual fisher and government body. This will help give fishers a more centralised consensus-driven voice in business and likely support microfinance programmes that could be used to get certain sectors off the ground with new technologies/innovations. This may also facilitate entrepreneurship and likely facilitate private sector investment.

- Promote programmes through government that incentivise data capture, e.g., subscription models in which the government initially pays cooperative groups for data collection to get foundational databases up and running.

- Promote more government spending on baseline research to highlight data gaps that may limit innovation in the sector.

The base: Enabling environments for digitalisation

- Help governments develop policies and legislation (when required) to facilitate digitalisation (e.g., data sharing agreements, incentivisation/funding programmes, better digital policies, industry-government partnership agreements and ultimately better investment in infrastructure).

- Encourage governments to reduce costs for connectivity/broadband.

- Undertake national surveys to identify target areas that are ready for innovation as well as areas that will need to be brought up to speed so that they can receive innovation that may be present in other areas.

- Promote knowledge sharing through the promotion of case studies and the exchange of experiences between stakeholders. This will help support the utilisation of digital fisheries.

We see the biggest need for digitalisation across the SSF in African, Asian and Pacific SIDS and believe that with more detailed research on a national level, opportunities for smooth and coherent digitalisation will clearly present themselves. In terms of further work, looking at digitalisation per country through KI engagement with country-specific governments would be beneficial. This would allow for digitalisation within Commonwealth fisheries to be understood at a higher resolution and more tailored recommendations to be made. Working groups with different relevant stakeholders per country of interest would be invaluable for this process, as would investigating neighbouring countries to uncover any impacts from outside of specific countries themselves.

[1] Bennett, N.J., Finkbeiner, E.M., Ban, N.C., Belhabib, D., Jupiter, S.D., Kittinger, J.N. Mangubhai, S., Scholtens, J., Gill, D. and Christie, P. (2020) ‘The COVID-19 Pandemic, Small-Scale Fisheries and Coastal Fishing Communities’. Coastal Management 48, 336–347.

[2] Towards Integrated Assessment and Advice in Small-Scale Fisheries: Principles and Processes (2008) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.