5.0 Commonwealth Pacific

5.1 Fisheries profile in the Pacific

Capture fisheries within the region produce over 1,000,000 metric tonnes annually (Table 5.1). Within the SIDS of the Pacific Commonwealth (Figure 5.1), a great deal of the food, well-being, way of life, fiscal revenue and employment is based on their fish stocks, especially tuna.[1]

Table 5.1: Pacific fishery profile.

|

|

Sector |

Statistic |

|

Total annual production |

Capture fisheries production (metric tons) - Pacific Island small states, Australia, New Zealand |

1,178,313 tonnes |

|

Inland fisheries |

0.02 million tonnes |

|

|

Aquaculture |

205.3 million tonnes |

|

|

Sources |

||

|

Contribution to GDP |

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP) - Pacific Island small states, Australia, New Zealand |

20.232 |

|

Employment |

Fisheries |

2,457,000 |

|

Aquaculture |

12,000 |

|

|

Sources |

||

|

Consumption

|

Per capita food fish consumption |

24.2 (kg/year) |

|

Sources |

Whilst the Pacific Commonwealth SIDS benefit economically from LSF tuna operations, much of their national fisheries (in terms of employment) revolve around far less lucrative SSF operations. In comparison, Australia and New Zealand boast of well-established commercial fisheries[2] both within the small- and large-scale sectors with fishery product exports amounting to billions of dollars annually.[3] Although tuna fisheries play a dominant role in the region, for the surrounding SIDS, these tuna fisheries are often dominated by foreign fishing fleets from China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Philippines, Taiwan and the USA.[4]

Figure 5.1. Map of Pacific countries that are part of the Commonwealth.

The Small Island Developing nations (SIDS) include: Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Samoa, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu.

A significant feature of Pacific fisheries is the strong regional organisations operating within the sector.[5] For example, the Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) based in Solomon Islands, which aids member states in managing the region’s tuna stocks, invests in programmes surrounding economic resilience, surveillance, legal advice, media and training.[6] Despite the diversity within the Pacific Commonwealth states, there is a lot of overlap regarding the systemic issues facing the fisheries sectors in the region.

5.2 Digitalisation in Pacific fisheries

Digitalisation within the Pacific Commonwealth fisheries faces multiple challenges. The region’s fisheries, in particular those of SIDS, are heavily reliant on tuna fisheries for both economic development and food security.[7] Despite the Pacific region possessing the healthiest tuna stocks globally[8] catches within the area are declining overall.[9] Furthermore, these stocks are highly migratory and are predicted to head further east due to climate change.[10] A 2021, a modelling study reported that at the current rate of warming, tuna catch rates within the waters of Pacific SIDS could decline by an average of 20 per cent by 2050.[11] As a result, the sector needs to find alternative ways to add value to a revenue source that looks to be in consistent decline over the long term.

5.3 Pillar 1 – Digital innovations in Pacific fisheries

Digital innovations in the Pacific’s fisheries have been described as “substantially underway” as there are several pilots and initiatives currently in progress. In general, accessibility and knowledge of digital technologies within the region is considered “good”, but progress is disjointed and inconsistent. The region often suffers from an inability to roll-out new technologies at scale to cover the whole fishery, and there is little drive from deep water fishing nations operating in the region to support capacity building efforts. Accessibility to digital technologies, such as the Fisheries Information and Management System purchased by the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), is largely facilitated by the Pacific Islands FFA in collaboration with Secretariat of Pacific Community (SPC), which works across all countries within the region.

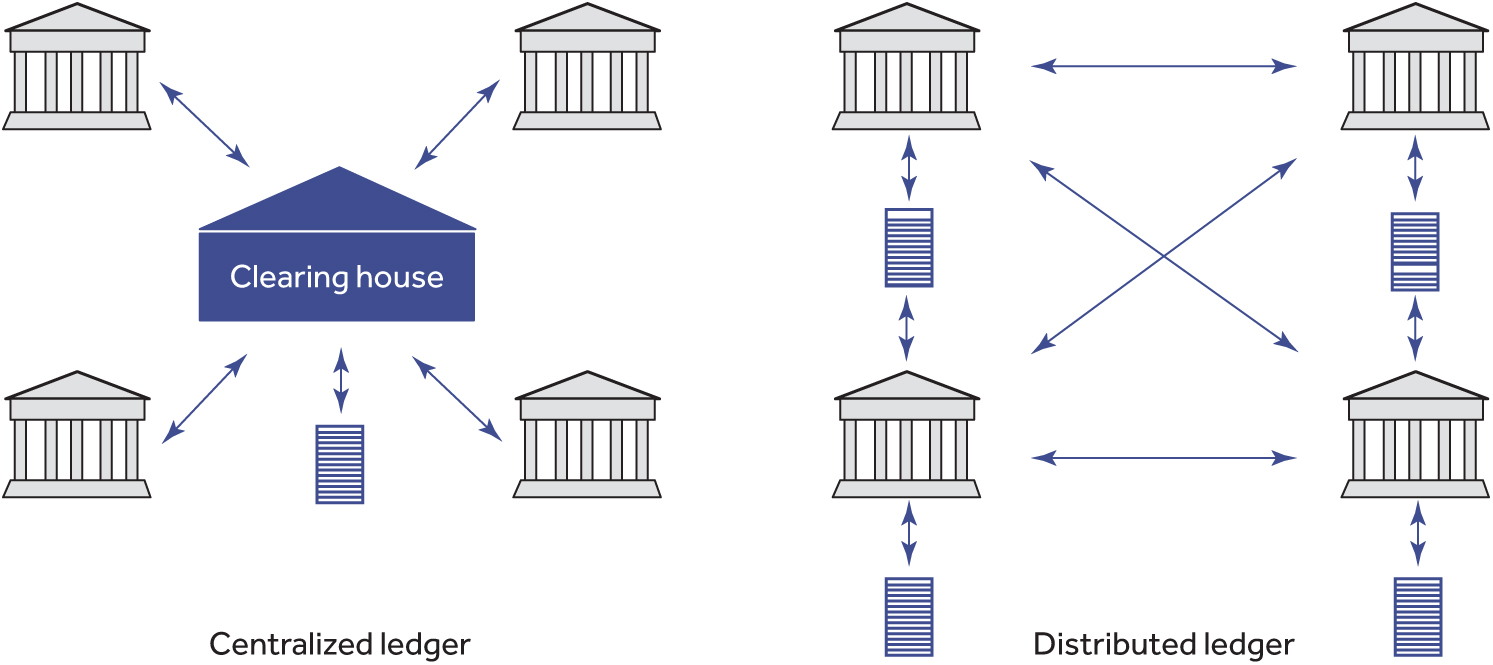

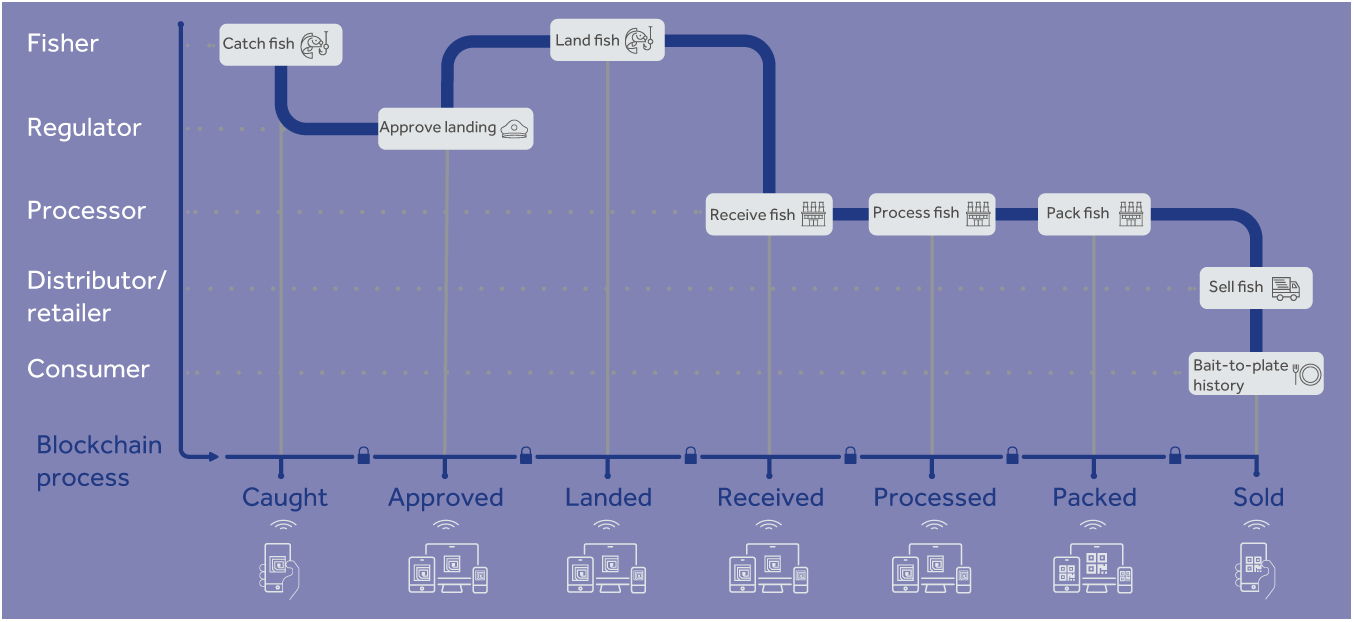

Digital technologies being used within the region’s fisheries have, in some cases, been industry firsts, such as the use of blockchain technologies for supply chain traceability in Pacific tuna fisheries.[12] “Blockchain technology” is a decentralised and distributed digital ledger of transactions (Figure 22) that is replicated on every node, or participant, in the network.[13] Within the fisheries sector, blockchain can be used to store details about where and when a fish was caught, which vessel caught the fish and what method was used to catch the fish. This information can then be accessed throughout the supply chain from processors to the customers at point of purchase.[14] The ability to guarantee a solid chain of information from “bait to plate” can help reduce IUU fishing activities, misinformation and seafood fraud.[15] The ability to do this often facilitates successful application to sustainable certification programmes, thus adding value to the seafood products that benefit from such technologies.

Figure 5.2: Illustration of the difference between centralised and decentralised ledgers.

Blockchain technology benefits from decentralized (distributed) ledgers. Source: http://www.fao.org/3/ca8751en/ca8751en.pdf [accessed: 29/09/2021]

The first application of blockchain technology within a Pacific tuna longline fishery was established in 2017 during a collaborative project in Fiji. The WWF, ConsenSys, and Fijian companies Sea Quest (Fiji) Ltd and TraSeable Solutions partnered with the aim of “utilising innovative blockchain technology, for the fresh and frozen tuna supply chain”.[16] To do so, the supply chain was mapped into Treum, previously known as Viant (Figure 5.3), which is a company owned by ConsenSys (project partner) who specialise in the application of blockchain technologies in supply chains.[17] Mapping of the supply chain was necessary to digitise each stage of the supply chain as Sea Quest, the fishing company involved with the project, at the time was still reliant on manual data collection.[18] Treum is a blockchain-based platform for modelling business processes, tracking assets and building transparent, flexible supply chains of the future that run on the “Ethereum” blockchain platform.[19]

Figure 5.3: Viant tuna process flow diagram used to describe the Fijian longline tuna project run by WWF in collaboration with ConsenSys, and Fijian companies Sea Quest (Fiji) Ltd and TraSeable Solutions.

Source: http://awsassets.wwfnz.panda.org/downloads/draft_blockchain_report_1_4_1.pdf [accessed 29/09/2021]

Each tuna landed by a longliner enrolled in the project is tagged with a unique identifier. Initially, this was done using re-useable radio frequency identification (RFID) tags but later swapped for QR codes as the RFID tags had to be imported to Fiji which was both difficult and costly. Key information about the capture event of each tuna as well as data about the tuna itself are recorded and uploaded via a mobile phone application. This data is then transmitted in real time to the blockchain, or if Internet connection is not available at the time of capture, upon return to the port. When the tuna is landed and unloaded, the QR code is rescanned. The tuna is then tracked at all key stages along the processing line and key data is collected. If the tuna is processed into other products, such as loins, the new product is given a new identity on the blockchain and tracked separately. Distributors can then choose to participate and continue to track the tuna/product through the supply chain to the consumer.[20] Having access to this information about each fish as it journeys through the supply chain means processors, distributors and consumers can ensure their tuna has been caught sustainably and legally. This helps prevents fish caught by IUU fisheries from entering the supply chain.[21]

Although success stories such as the aforementioned WWF-led project highlight the utility of blockchain technologies to improve fisheries chain of custody information, there are still many limitations associated with them. Limitations arise from a reliance on human inputs, such as when inputting catch information into an app, which leaves still the system open to tampering. Secondly, physical tags and labels used to track fish can be tampered with or fall off and/or become damaged during transportation, thus preventing the fish from being tracked. The verifiability of private and consortium blockchain platforms also presents a traceability and transparency issue, as these blockchain networks are not open to the public which prevents transactions from being independently verified.[22]

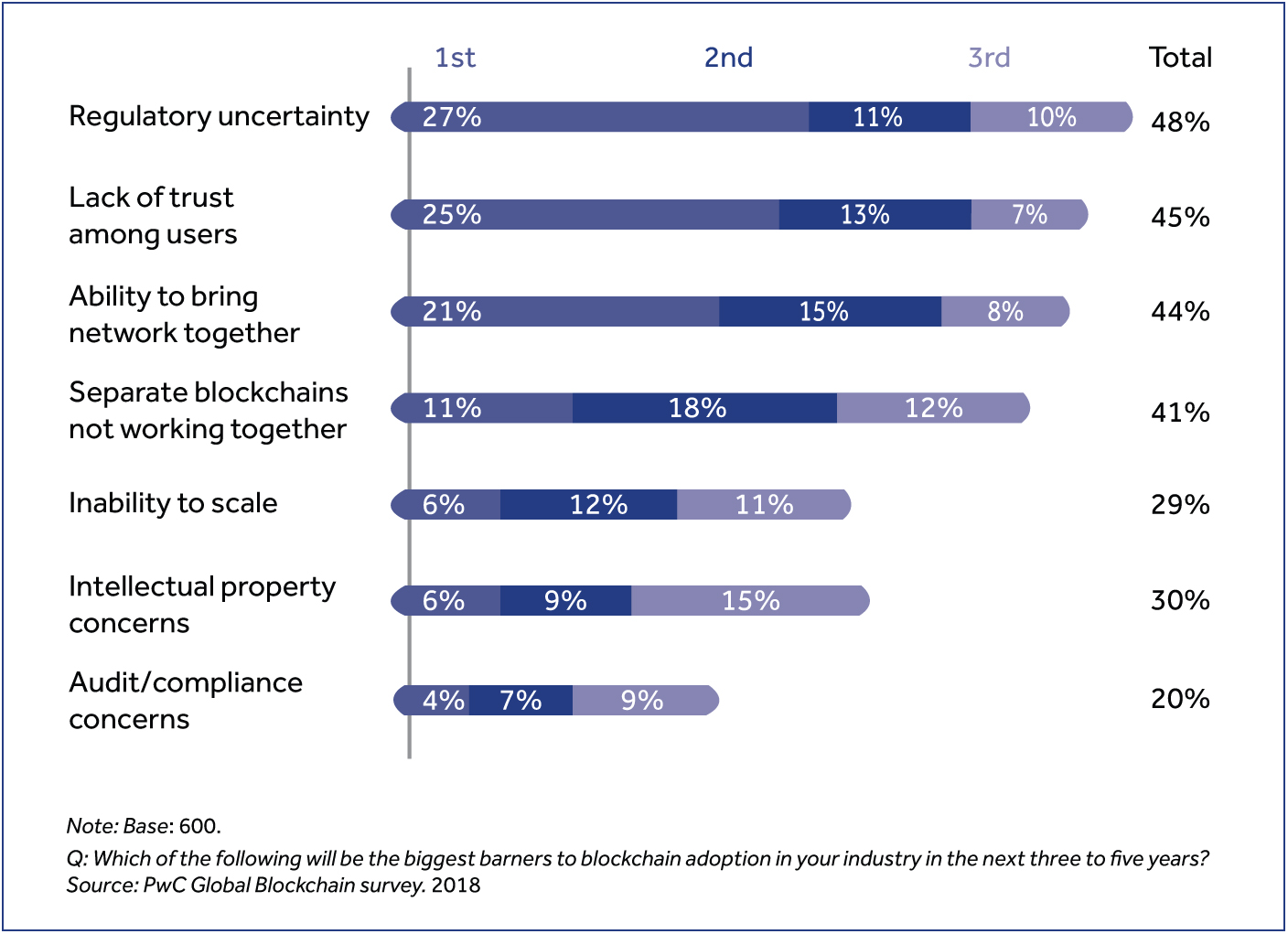

Adoption of blockchain, and other modern technologies and solutions, ultimately relies on being able to access the required infrastructure and technologies, such as the Internet and mobile phones,[23] which is lacking in some areas of the Pacific. Adoption also relies on several additional factors complicating matters (Figure 5.4). Furthermore, while blockchain technology is being used by other players within the seafood sector, for blockchain to reach its full potential within fisheries supply chains relies on push from the global seafood market declaring that they want this level of transparency and are willing to invest in it.[24]

Figure 5.4: Main barriers to blockchain adoption with percentage of respondents ranking top 3 barriers to blockchain adoption.

Source: https://www.pwccn.com/en/research-and-insights/publications/global-blockchain-survey-2018/global-blockchain-survey-2018-report.pdf [accessed 29/09/2021]

However, the introduction of the SpaceX Starlink satellite constellation has been marked by many as a solution to rural digital connectivity problems in the global south[25] through offering satellite internet. Satellite Internet enables the users to connect to the Internet directly by satellites orbiting the earth, thus eliminating the need for a stable ground-based connection. SpaceX CEO states that connection to the Internet at sea will be “relatively easy”, with external reports stating users could have access to 100 megabits per second download speeds and 40 megabits per second upload speeds at sea through the Starlink network.[26]

The Pacific region has also seen the rollout of digital monitoring technologies within commercial fishing fleets. Electronic reporting is being implemented across the region, while electronic reporting for fisheries observers is increasingly being deployed.[27] Electronic reporting has been active in the region’s longline fleet for almost a decade with organisations such as the Western & Central Pacific Fisheries Commission,[28] PNA[29] and the SPC,[30] all having electronic monitoring standards groups.

In September 2020, the New Zealand fisheries minister announced plans to put video cameras on board 345 fishing vessels across the nations inshore fishing fleet.[31] The aim was to improve fisheries management, information and transparency within the sector to appeal to the wider global markets.[32] The roll-out of video cameras for monitoring purposes within the Pacific has sustainability issues as many commercial fisheries do not see the value of installing video cameras to comply with such programmes. Fishers also do not get access to the data collected from the video monitoring which acts as a further deterrent. Some believe that if governments make investing in monitoring technologies, such as video cameras compulsory for vessels, they may risk losing fleets to other countries in the case of foreign vessels that fish as part of fishery agreements.

5.4 Pillar 2 – Data infrastructure in Pacific fisheries

Overall, the Pacific region’s digital data infrastructure is underdeveloped and fragmented at the national level. This applies to the Pacific SIDS and across Australian and New Zealand fisheries. Currently, some SIDS within the Pacific are still collecting data on paper, although generally, this practice is being phased out. Regional fisheries agencies over the years have invested heavily in improved data collection systems, and as a result, data for larger-scale offshore fisheries within the Pacific Islands is generally good.

In 2015, Pacific leaders announced that the development of a regional ICT initiative was one of the top five priorities in the region, with a focus on economic development and education.[33] Despite this, countries, development agencies and sectors focused on their own issues and priorities rather than adopting a region-wide approach to addressing development challenges. For example, some felt that a consortium among Pacific Islands countries to collectively purchase bandwidth at a cheaper rate was the way forward, while others suggested using TongaSat satellites to provide satellite services to the region, but none of these ideas came to fruition.[34] More recently, however, connectivity in the Pacific SIDs has been improving. For example, Kiribati is set to have fibre optic broadband go live in April 2022,[35] while the “Tuvalu Telecommunications and ICT Development Project” is working with the support from the World Bank in the form of a $29 million USD grant to develop the nation’s Internet access network.[36]

Although there is data available, there are issues with the capacity of the region to make sense of the data collected as there is a lack of professional infrastructure and data analysts. For example, in New Zealand, their data warehouse is largely unused as it takes 6–9 months for data to be input, and thus, there are issues with storing the large amounts of fisheries data collected by the government. Despite New Zealand’s fisheries being data rich, the lack of professional data infrastructure means their capacity to effectively use data is stunted. While training, outreach and digitisation of the data collecting process could improve the region’s fisheries data, and issues with data storage and transmission must be first addressed so that data collected can be effectively stored and used. One programme aiming to address this is the SPC’s “Tuna Fisheries Data Management system” (TUFMAN2). TUFMAN2 is a cloud-hosted, web database developed for Pacific Island Communities to manage their tuna fishery data.[37]

Efforts are being made, however, to improve fisheries data and related infrastructure in the Pacific region. In April 2021, the Australian Government announced that it was injecting $20 million AUD into an electronic monitoring programme, and data integration, monitoring and AI to reduce regulatory burden, increase productivity, support new export opportunities and improve environmental outcomes for Australia’s Commonwealth fishers.[38] The Minister for Agriculture, David Littleproud, stated that the new initiative “E-Fish” will provide the sector with “leading-edge, fit for purpose data systems” that will deliver “cheaper and more efficient services” to commercial fishers. The new system is said to streamline and integrate fisheries data and its collection to increase flexibility for operators and reduce the costs of administration.[39]

5.5 Pillar 3 – Business development services in Pacific fisheries

One of the greatest business development issues facing digitalisation within Pacific fisheries is “institutional inertia”, which refers to the resistance of the sector to change. For example, the commercial fisheries sector of the region is keen to advance in terms of digitalisation, but they are hindered in part by the desire of governments to control fisheries data and not share it as well as reluctance to alter the way things are done. This government top-down data collection, management and storage approach makes it difficult for external companies to innovate and become involved in the fisheries sector.

Business development in terms of digitalisation within the sector is also hindered by the lack of sustainable funding. Currently, much of the digitalisation within the sector is reliant on donor funding, which is almost always limited in time and scope. Funding for digitalisation pilots tends to be reliant on NGOs, and many successful projects fail over the long term because they do not receive funding after the initial project start-up costs. In addition, very few project build in business models that allow for self-perpetuating funding, thus making them reliant on external injection of capital to maintain operations. Government funding within the region is being poured into modernisation efforts in some instances, for example, Australia and New Zealand are making efforts to implement cost recovery mechanisms to ensure digital initiatives are sustainable in the long term. However, as with donor funding, such government funding is limited in time and scope.

5.6 The base – Enabling environments for digitalisation within Pacific fisheries

Most innovation within the fisheries sector digitalisation journey is being undertaken by small- to medium-sized fishing operators regarding product sales in the Pacific Islands. The challenge faced by many relates to economies of scale – meeting the volume requirements that larger retailers face. This highlights a wider-scale problem for fisheries digitalisation, specifically in the Pacific Islands. Access to the appropriate data infrastructures is limited (both by cost and connectivity) for smaller enterprises, which limits the scope of development for digitalisation projects. Growth is also further hindered by Pacific Island governments, who although keen to improve fisheries management and economies, are generally concerned about the viability and uptake of digitalisation programmes. This potential bottleneck which has developed via government mentality is exacerbated by questions of funding past pilot stages of projects: “Who will fund the project in the long-term?” This is a common question that many do not know the answer to.

Fisheries data across the Pacific region is generally good (at least for the LSF), but this data is not yet being used to its full potential in decision-making. This means governments are potentially not considering the full scope/utility of data produced and mobilised from digitalisation and therefore still, widely speaking rhetorically with no concrete plans for the future of fisheries digitalisation in the region. In addition, many believe that certain leaders fear failure regarding new innovations. It is, therefore, common for leaders to sit safely in rhetoric which purports forward-thinking mentalities but does not practically promote or implement change towards increased digitalisation. In some cases, the remoteness of the SIDS within the region can hinder digitalisation efforts. For example, many of the region’s SIDS lack access to sufficient bandwidth for Internet access, network coverage and, in some cases, power which clearly limits the use of many digital technologies. Remote communities also struggle with attracting the expertise and capacity necessary to install and maintain new technologies, something which is also exacerbated by the limited resources allocated to fisheries bodies within the region.

The legislative environment across the Pacific Commonwealth also hinders digitalisation although the FFA has been instrumental in supporting island nations update their regulation in support of digitalisation so there is a sound legal foundation for implementing technology. Digitalisation must now focus on capacity building in the island nations because at present the skill needed to implement and run such projects is not available and most skilled workers with the necessary education are not based in the islands.

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆

[1] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[2] Lambeth, L., B. Hanchard, H. Aslin and L. Fay-Sauni (2014) ‘An Overview of the Involvement of Women in Fisheries Activities in Oceania’, 17.

[3] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[4] FAO. Pacific Fisheries. http://www.fao.org/3/am014e/am014e05.pdf

[5] Gillett, R.D., Tauati, M. Ikatonga and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018) Fisheries of the Pacific Islands: Regional and National Information.

[6] Executive | Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) (2013) https://www.ffa.int/executive

[7] Bell, J.D. Denina,I., Adams, T., Aumont, O., Calmettes, B., Clark, S., Dessert, M., Gehlen, M., Gorgues, T., Hampton, J., Hanich, Q., Harden-Davies, H., Hare, S.R., Holmes, G., Lehodey, P., Lengaigne, M., Mansfield, W., Menkes, C., Nicol, S., Ota, Y., Pasisi, C., Pilling, G., Reid, C., Ronneberg, E., Gupta, A.S., Seto, K.L., Smith, N., Taei, S., Tsamenyi, M., and Williams, P. (2021) ‘Pathways to Sustaining Tuna-Dependent Pacific Island Economies during Climate Change’. Nature Sustainability 1–11. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00745-z.

[8] Healthy Tuna Stocks in the Pacific Pave the Way for Strategic Sustainable Fisheries Management (2019) The Pacific Community. https://www.spc.int/updates/news/2019/12/healthy-tuna-stocks-in-the-pacific-pave-the-way-for-strategic-sustainable

[9] Tuna | Species | WWF. World Wildlife Fund. https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/tuna

[10] Bell, J., K. Seto, Q. Hanich and S. Nicol (2021) ‘Climate Change is Causing Tuna to Migrate, Which Could Spell Catastrophe for the Small Islands That Depend on Them’. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/climate-change-is-causing-tuna-to-migrate-which-could-spell-catastrophe-for-the-small-islands-that-depend-on-them-164000

[11] Bell, J.D. Denina,I., Adams, T., Aumont, O., Calmettes, B., Clark, S., Dessert, M., Gehlen, M., Gorgues, T., Hampton, J., Hanich, Q., Harden-Davies, H., Hare, S.R., Holmes, G., Lehodey, P., Lengaigne, M., Mansfield, W., Menkes, C., Nicol, S., Ota, Y., Pasisi, C., Pilling, G., Reid, C., Ronneberg, E., Gupta, A.S., Seto, K.L., Smith, N., Taei, S., Tsamenyi, M., and Williams, P. (2021) ‘Pathways to Sustaining Tuna-Dependent Pacific Island Economies during Climate Change’. Nature Sustainability 1–11. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00745-z.

[12] New Blockchain Project Has Potential to Revolutionise Seafood Industry. https://www.wwf.org.nz/what_we_do/marine/blockchain_tuna_project/

[13] FAO (2020) Blockchain Application in Seafood Value Chains. doi:10.4060/ca8751en.

[14] Ellen, R. (2021) ‘Blockchain Supply Chain Traceability Project’. Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. https://www.pmcsa.ac.nz/2021/02/21/blockchain-supply-chain-traceability-project/

[15] From Bait to Plate. World Wildlife Fund. https://www.worldwildlife.org/pages/bait-to-plate

[16] Cook, B. (2018) ‘Blockchain: Transforming the Seafood Supply Chain’, 41.

[17] FAO (2020) Blockchain Application in Seafood Value Chains. doi:10.4060/ca8751en.

[18] FAO (2020) Blockchain Application in Seafood Value Chains. doi:10.4060/ca8751en.

[19] Cook, B. (2018) ‘Blockchain: Transforming the Seafood Supply Chain’, 41.

[20] FAO (2020) Blockchain Application in Seafood Value Chains. doi:10.4060/ca8751en.

[21] Ellen, R. (2021) ‘Blockchain Supply Chain Traceability Project’. Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. https://www.pmcsa.ac.nz/2021/02/21/blockchain-supply-chain-traceability-project/

[22] FAO (2020) Blockchain Application in Seafood Value Chains. doi:10.4060/ca8751en.

[23] Ellen, R. (2021) ‘Blockchain Supply Chain Traceability Project’. Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. https://www.pmcsa.ac.nz/2021/02/21/blockchain-supply-chain-traceability-project/

[24] Using blockchain to bring transparency from sea to plate | Reuters Events | Sustainable Business (2020) https://www.reutersevents.com/sustainability/using-blockchain-bring-transparency-sea-plate

[25] Herath, H.M.V.R. (2021) ‘Starlink: A Solution to the Digital Connectivity Divide in Education in the Global South’. ArXiv211009225 Cs.

[26] SpaceX Starlink: Will it work at sea? Elon Musk weighs in. Inverse. https://www.inverse.com/innovation/starlink-will-it-work-on-boats

[27] Electronic monitoring. Pacific Fishery Management Council. https://www.pcouncil.org/managed_fishery/electronic-monitoring/

[28] Western & Central Pacific Fisheries Commission. Compliance Monitoring Scheme | WCPFC. https://www.wcpfc.int/compliance-monitoring

[29] The Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA). Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA). https://www.pnatuna.com/

[30] Secretariat of Pacific Community (SPC). E-Reporting. https://oceanfish.spc.int/ofpsection/data-management/wcpfc/337-e-reporting?lang=en

[31] Industries, M. for P. On-board cameras for commercial fishing vessels | MPI – Ministry for Primary Industries. A New Zealand Government Department. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/fishing-aquaculture/commercial-fishing/fisheries-change-programme/on-board-cameras-for-commercial-fishing-vessels/

[32] New Zealand introduces plan to put camera aboard all its fishing vessels (2020) https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/environment-sustainability/new-zealand-introduces-plan-to-put-camera-aboard-all-its-fishing-vessels

[33] United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (2019) Satellite Communications in Pacific Island Countries. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Satellite%20Communications%20in%20Pacific%20Island%20Countries.pdf

[34] United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (2019) Satellite Communications in Pacific Island Countries. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Satellite%20Communications%20in%20Pacific%20Island%20Countries.pdf

[35] Putt, S. (2021) ‘NZ Fry Up: Tokelau and Kiribati join the fibre broadband party; Ransomware: to pay or not to pay?’ Computerworld. https://www.computerworld.com/article/3623817/nz-fry-up-tokelau-and-kiribati-join-the-fibre-broadband-party-ransomware-to-pay-or-not-to-pay.html

[36] The World Bank (2019) Affordable, Faster Connectivity for Tuvalu. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/01/15/affordable-faster-connectivity-for-tuvalu

[37] Tuna Fisheries Data Management system (TUFMAN2). https://oceanfish.spc.int/en/ofpsection/data-management/spc-members/dd/502-tufman2

[38] News, M. (2021) ‘$20 Million to Revolutionise Commonwealth Fisheries’. Mirage News. https://www.miragenews.com/20-million-to-revolutionise-commonwealth-546350/

[39] News, M. (2021) ‘$20 Million to Revolutionise Commonwealth Fisheries’. Mirage News. https://www.miragenews.com/20-million-to-revolutionise-commonwealth-546350/

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆