4.0 Commonwealth Caribbean and the Americas

4.1 Fisheries profile in the Caribbean and the Americas

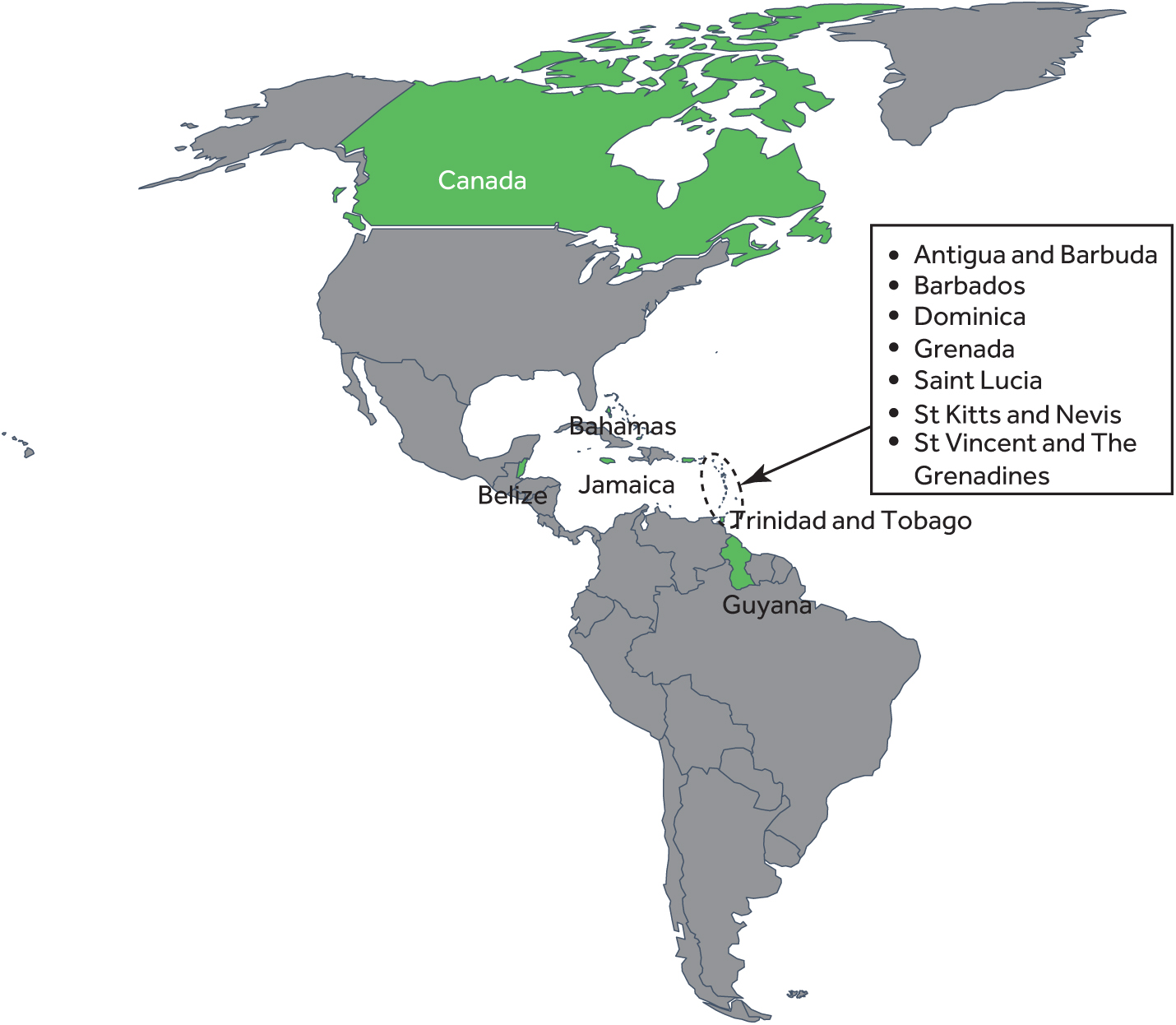

Capture fisheries within the region produce over 15,000,000 metric tonnes annually (Table 4.1). In the Commonwealth Caribbean, there are ten sovereign states, six British Overseas Territories and two independent mainland nations (Figure 4.1). Marine fishing industries in the region are largely characterised by SSF that are fundamental in employing and feeding the populations of the Caribbean’s small island states (Figure 4.2) and in some cases acting as products of national export.

Table 4.1: The Americas and Caribbean fishery profile.

|

|

Sector |

Statistic |

|

Total annual production |

Capture fisheries production: Latin America & Caribbean, Canada |

15,707,921 tonnes |

|

Inland fisheries |

0.63 million tonnes |

|

|

Aquaculture |

3799 million tonnes |

|

|

Sources |

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.FSH.CAPT.MT?locations=ZJ-CA |

|

|

Contribution to GDP |

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP): Latin America & Caribbean, Canada |

7.515 |

|

Sources |

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.AGR.TOTL.ZS?end=2020&locations=XU-ZJ-CA&start=2020&view=bar |

|

|

Employment |

Fisheries |

2,455,000 |

|

Aquaculture |

388,00 |

|

|

Sources |

||

|

Consumption

|

Per capita food fish consumption |

32.9 (kg/year) |

|

Sources |

Figure 4.1: Map of North and South America showing the Commonwealth countries.

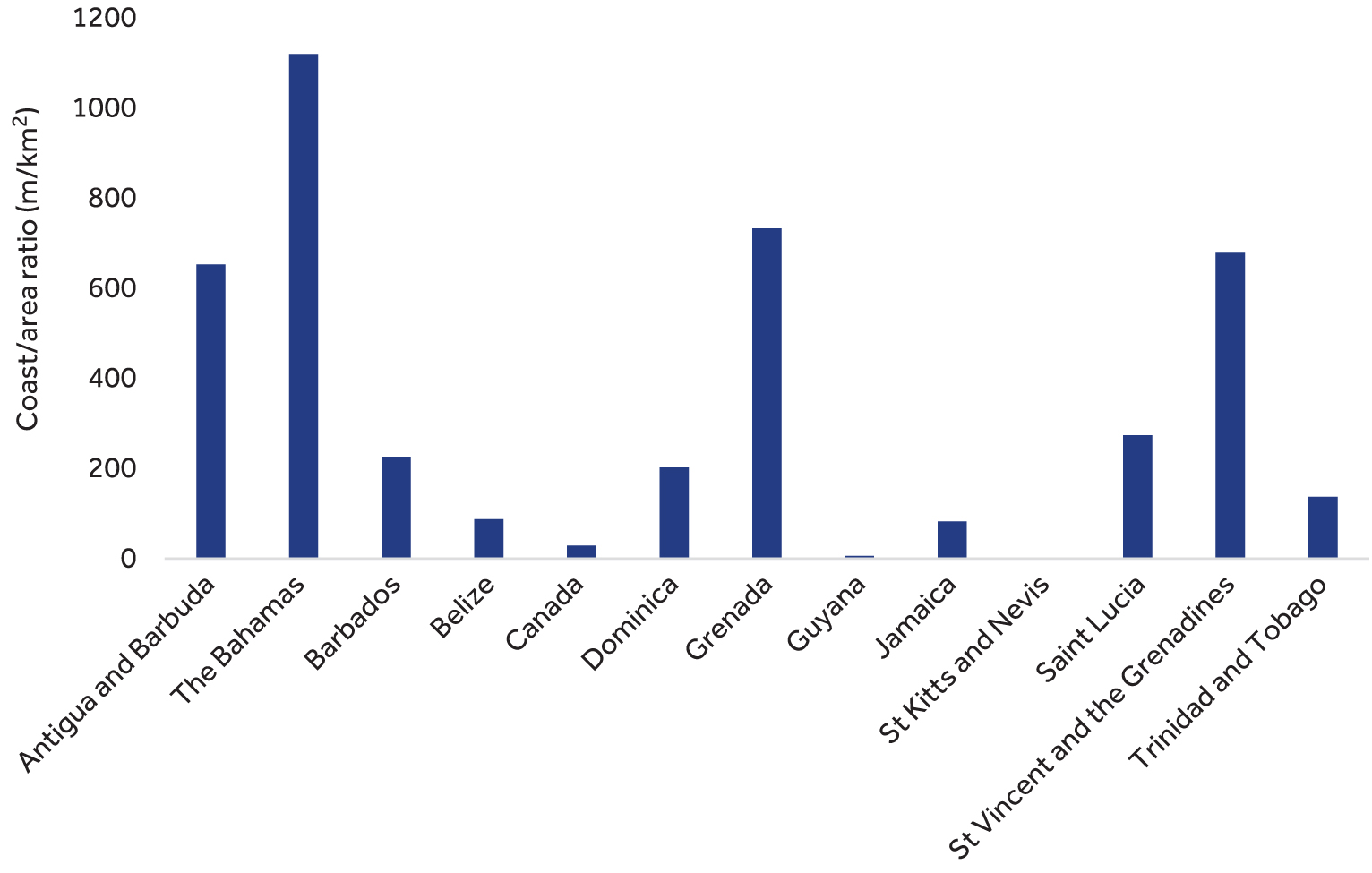

Figure 4.2: Coastline to land area ratio for Caribbean and the Americas Commonwealth countries.

In some instances, this ratio can be used as a useful indicator for a country’s reliance on fisheries resources.

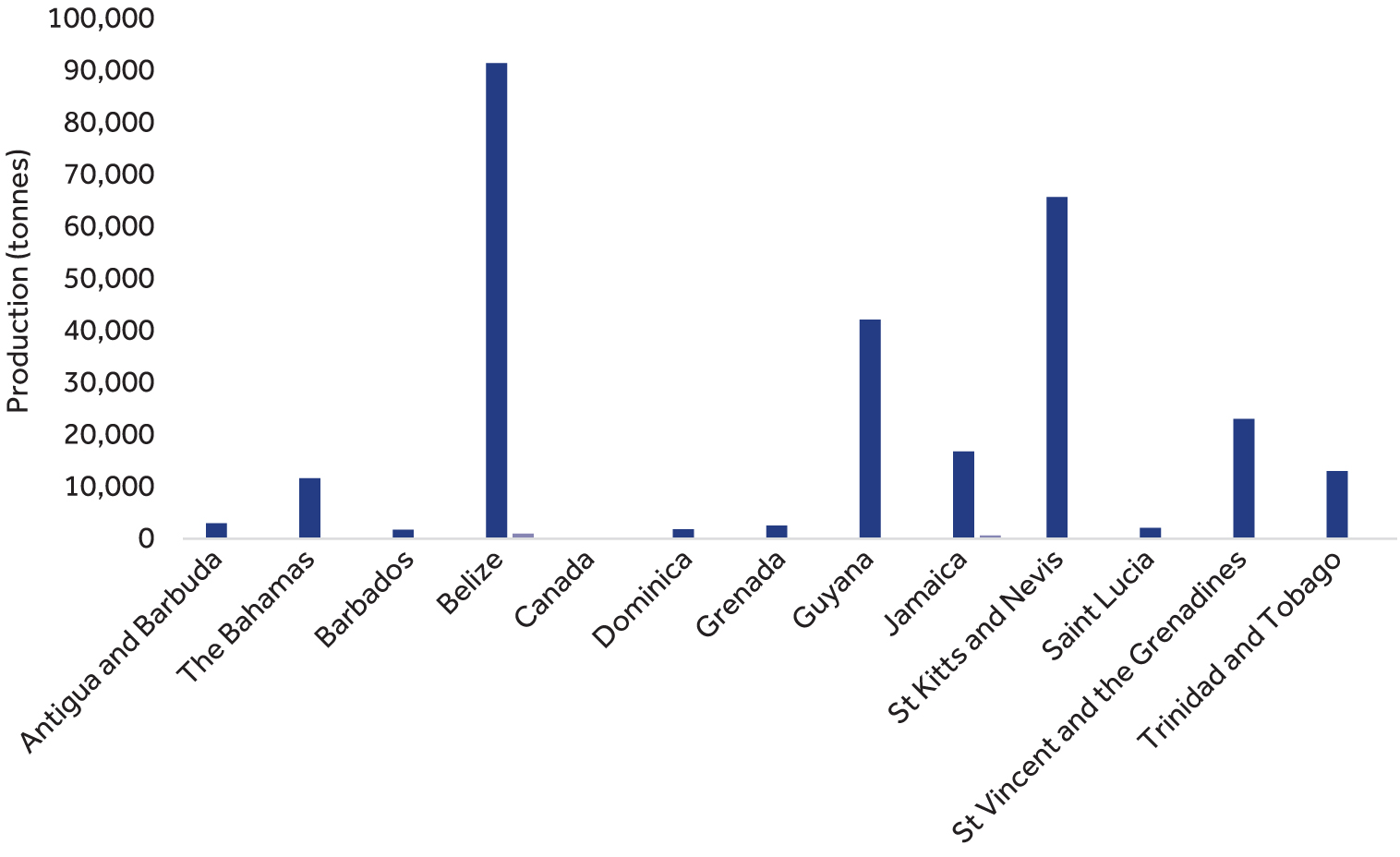

Figure 4.3: Capture fisheries and aquaculture production for Caribbean and the Americas Commonwealth countries.

Canada’s production removed for visualisation purposes (fisheries = 874,777, aquaculture = 200,765). Blue bars = fisheries, orange bars = aquaculture Source: World Bank (2018-2019).

For Commonwealth countries like Guyana and Belize, fisheries contribute a significant proportion higher of national gross domestic product (GDP) (1.9 per cent in 2012[1] and 3 per cent in 2015,[2] respectively). For some states with significant inland water resources like Guyana, freshwater fisheries also make up an important source of livelihoods, traditions and national nutrition.[3]

Fisheries production in Canada is by far the largest in the Caribbean and North American Commonwealth region (Figure 18). In 2018, Canada’s commercial fisheries, including marine and freshwater fisheries, contributed over $3.7 billion USD to the national economy, while employing 45,907 people. Fish and seafood processors, including product preparation and packaging, contributed over $6.6 billion USD and employed 26,429 people in 2018 alone.[4] Canada’s commercial fisheries operate in three broad regions: the Atlantic Ocean, the Pacific Ocean and inland, mostly near the Great Lakes and Winnipeg.[5] Fisheries within the Atlantic Ocean account for ~81 per cent of total capture production and have historically been dominated by large volume fisheries for demersal and small pelagic species (Figure 18). Fisheries on the Pacific coast are more diverse in terms of species, and salmon fisheries play a greater role in the sector. Asides from commercial fisheries, Canada’s marine and aquatic ecosystems are relied on First Nations peoples and play a fundamental role in their history, culture, economies and self-sufficiency.[6]

4.2 Digitalisation in the Caribbean and Americas fisheries

4.2.1 Caribbean

Digitalisation efforts within the Caribbean Commonwealth fisheries face an array of challenges. Firstly, there is limited understanding of the full value and potential of the fisheries sector. However, the emergence of the Blue Economy drive is drawing more attention to fisheries as an industry and solutions for optimising its benefits. Secondly, the traditional culture of the fisheries sector limits scope for digital innovation and uptake within the industry. A lack of innovation and uptake within the sector is further amplified by digital illiteracy.

4.2.2 Canada

Canada’s fisheries sector faces challenges in terms of productivity. The seasonality of the industry is thought to be partly to blame, along with limited innovation and modernisation of the fisheries sector.[7] In Canada, digitalisation has been described as “ubiquitous” but uneven across industries. A 2021 study that reviewed digital “intensity” within the production sectors of Canada’s economy between 2000 and 2015 ranked agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting “low” in terms of digital intensity.[8]

4.3 Pillar 1 – Digital innovations in the Caribbean and Americas fisheries

4.3.1 Caribbean: Digital technologies and digital solutions and services

The current state of digital innovations within the Caribbean’s fisheries sector is considered “low”, with fishers in the region mainly relying on basic digital solutions and services such as voice calls, WhatsApp messaging and Microsoft Word and Excel for data collection and storage. However, the sector is benefitting from new digital payment platforms that make conducting business easier, reduce barriers to entry for entrepreneurs and improve the efficiencies and effectiveness of fisheries authorities. For example, in April 2021, the Eastern Caribbean created its own form of digital currency to help speed up transactions and serve people without bank accounts. The Eastern Central Bank said that “DCash” is the first blockchain-based currency to be introduced by one of the world’s currency unions, although some individual nations have similar existing systems.[9] DCash differs from cryptocurrencies as it is issued by an official bank and has a fixed value in line with the existing Easter Caribbean dollar. The DCash system allows users with a smartphone to use a mobile phone app to make payments via a QR code. This is possible even for users without a bank account.[10]

More advanced digital technologies, including blockchain and AI, are not currently being used within the sector, but there is some use of cloud-based systems for data storage beginning. There are no access limitations to the use of these advanced technologies for basic operations, and policies and regulatory frameworks for their use in privacy and security matters are not yet fully established.

Although digital innovations in Caribbean fisheries may be considered under-developed at present, there are some important solutions and services in early developmental stages, with pilots currently being undertaken. High adoption rates of smartphones among fishers in the Caribbean[11] also points towards a positive future for the uptake of digital innovations in fisheries in the region. For example, the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (CRFM) and the University of the West Indies were recently involved in the development of a “Fisheries Early Warning and Emergency Response” (FEWER) system[12] (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4: Outreach materials for the Fisheries Early Warning and Emergency Response (FEWER) mobile phone application.

Source: https://caribppcr.org.jm/fewer-the-app-making-fisherfolk-more-secure/ [accessed: 29/09/2021].

FEWER is available as the mobile app on Android and iOS devices, as well as a web-based dashboard components, with fishers being able to download the mobile app free of charge. The FEWER app provides fishers with eight modules that aim to aid SSF in reducing risks such as storms, hurricanes and other dangerous sea conditions through hazard warnings and the ability to send and receive alerts. As well as offering fishers weather data, the app provides users access to local ecological knowledge, damage reporting, emergency procedures alongside a messaging app and emergency contacts. As such, the app aids fishers throughout the entire disaster response cycle and ensures that they are prepared in the event of a disaster and armed with the tools to act in the event of a disaster.[13] This is especially important considering 90 per cent of the 300,000 fishers in the region operate boats less than 12 m in length.

To ensure the app was accessible, FEWER was designed in consultation with the expected primary users, data, external service providers and system administrators. Since development, FEWER has been formally launched in St Lucia and the hosting infrastructure is being adopted by the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency[14] which should secure the long-term sustainability of the app. Despite the limited uptake of more advanced technologies like blockchain, AI and cloud-based services, the high uptake of smartphones in the Caribbean region is improving fishers’ safety at sea through initiatives such as FEWER.

Digital technologies are also slowly being integrated into the sector for MCS purposes. In Belize, drones are being used to monitor the Turneffe MPA.[15] In 2019, two units of amphibian “Aeromapper Talons” were successfully trailed in the Turneffe Atoll during a workshop held by the Zoological Society of London and the Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association. The drones, built by Canadian company Aeromao, were used to detect and document IUU fisheries activities as well as collect ecological information for conservation efforts, such as turtle, dolphin and sharks within the area. The MPA was delineated in 2012 but has been difficult to manage due to IUU fisheries, the remote location and high running costs associated with patrols being conducted on boats to look out for IUU activities.[16] The MPA also lacked regular systematic surveys for marine megafauna, restricted by high fuel costs and reliance on boat surveys. The use of drones for MCS offers the MPA managers and conservation officers a low-cost solution to monitor the area, thus aiding in the fight against IUU fisheries whilst also collecting important ecological data.

4.3.2 Canada: Digital technologies and digital solutions and services

Despite Canada’s fisheries sector posing great potential for modernisation and innovation to improve its performance, the sector struggles to compete with low-cost seafood production coming out of Asia and other western jurisdictions that are already strongly innovative.[17] Canada’s fisheries sector has not always lacked modernisation and innovation. In fact, Canada was the first country to pilot and implement electronic monitoring programmes in 1999.[18] Although Canada was an early adopter of electronic monitoring, there were no new fully adopted electronic monitoring programmes implemented between 2006 and 2020.[19]

The Canadian government recently, however, began investing in the use of more advanced technologies than standard vessel monitoring that relies upon onboard infrastructure per vessel and some amount of trust for the gear to be used correctly. In February 2021, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) launched a programme in collaboration with the Defence Research and Development Canada's Centre for Security Science, Global Affairs Canada and MDA to detect vessels engaging in IUU fishing.[20] The “Dark Vessel Detection” programme uses satellite technology to detect and track vessels who turn off their location transmitting devices, which is sometimes done to avoid MCS. The $7 million USD programme will provide state-of-the-art satellite data and analysis to small island nations and coastal states around the world that are affected by IUU.[21] Thus, Canada, despite considered “developed”, appears to be lagging compared to other regions in terms of innovation and modernisation in its fisheries.

4.4 Pillar 2 – Data infrastructure in the Caribbean and Americas fisheries

4.4.1 Caribbean

The availability of quality fisheries data in general is considered a limiting factor in the digitalisation of the Caribbean’s fisheries sector. Similarly, the required data infrastructure to collect such quality data is sorely lacking. Within the region, there is a paucity of available data in many key areas. Data is lacking regarding catch, fishing areas/zones, damage and loss at sea, ICT usage, ICT profiles of fisherfolk, marine communications infrastructure and granular marine environmental measurements. However, there is an ongoing work within the region to improve the quality and quantity of available fisheries data and promote regional data sharing to aid better fisheries management and ocean governance decisions. Several regional and multinational agencies have been working on various digital solutions to facilitate such data sharing, including the CRFM’s Portal, the FAO’s Western Central Atlantic Fishery Commission Fishery Resources Monitoring System partnership and its Data Collection Reference Framework.

In terms of improving fisheries data, the CRFM and the University of the West Indies partnered with ESSA Technologies Ltd. to carry out detailed assessments of the ecological and economic impacts of climate change on the Caribbean fisheries sector. The project ran pilot studies in six countries including Jamaica, Haiti, Dominica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada. The findings were collated and used to produce data and insights applicable to the entire region. The project also included the development of the CRFM data portal, which provides a platform for users to search, explore and download the outputs from projects associated with the CRFM.[22] The data portal has become a permanent fixture, and new datasets are added when they become available and the use of the portal is being promoted. Continuing to improve upon the region’s collection and utilisation of fisheries data, such as through the development of the CFRM data portal, will certainly aid digitalisation efforts within the sector.

4.4.2 Canada

The data and associated infrastructure surrounding Canadian fisheries is well resourced through DFO, with the “Fisheries and Aquaculture Science” programme alone having an annual budget of approximately $174.1M and 788 full-time employees responsible for various tasks including the monitoring, data collection and research that support sustainability in Canada’s fisheries.[23] DFO is also responsible for the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), which has a budget of $49.4 M annually and employees 324 staff. The CHS focuses on safety in Canada’s waters undertaking hydrographic surveys to measure, describe and chart the physical features of Canada’s marine and inland space. Data collected is used to produce up-to-date, timely and accurate information for use by domestic and international mariners, such as commercial shippers, recreational boaters and fishers, as well as to support Canada’s defence and maritime security.[24] DFO also states in the policy objectives of the “Fishery Monitoring Policy” that fisheries data must be “accessible”, meaning the data collected is to be readily available to those who require it, subject to restrictions including safeguards to protect sensitive information. Fisheries data is to be in a consistent, standardised form and so it can be integrated and analysed at the fishery, stock, population, regional and national levels, and DFO aims to make the fishery information available to data providers, subject to requirements under the Privacy Act, the Access to Information Act, the Fisheries Act and internal guidelines on the informal release of information.[25]

Despite the aforementioned investments in fisheries-related data collection programmes, Canada’s fisheries data is still somewhat lacking.[26] In 2016, a federal audit report was conducted by the Canadian Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development. This report found that issues with data availability and quality prevented DFO from defining reference points needed to assign health status zones for over 50 per cent of the 154 fish stocks they have examined. Following this report, DFO stated that they would work towards completing deliverables that would result in 133 new or revised products to increase the number of fish stocks that have the necessary data for successful and sustainable fisheries management. However, in the first three work plans (fiscal years 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20) released following the audit, only 38 per cent (51 products) of the expected products were completed and publicly documented – 145 (19 products) were reported to be ongoing, 40 per cent (53 products) delayed and 8 per cent (10 products) were suspended either due to data or modelling limitations.[27]

The management of salmon fisheries within Canada in particular is challenged by a lack of baseline data on salmon abundance, run timing and harvest rates in mixed-stock fisheries.[28] To combat this, Ocean Wise, Canada’s largest sustainable seafood recommendation programme, announced in May 2021 that they will be working with Nunavut fisheries organisations and Arctic communities to co-develop a sustainability assessment framework grounded in science and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (a form of Inuit traditional knowledge).[29]

Small-scale indigenous fisheries across the world are regularly excluded from management decisions.[30] This is often because fisheries managers typically rely on biological data on the health of fish stocks and environmental assessments of specific fishing techniques to determine if a fishery is being harvested sustainably. In Canada, DFO only consistently monitor the population health of the country’s most commercially relevant species, while many Nunavut fisheries are too small to be deemed commercially important nationally. While this may be considered effective from a biological and economic perspectives, this approach is criticised for perpetuating colonialism through its exclusion of indigenous fishers.[31] The associated costs of fisheries and environmental monitoring also makes it difficult for indigenous SSF to access Canada’s lucrative sustainable seafood markets, which can in turn exclude them from the economic stability they offer.[32] To fully facilitate and benefit from digitalisation, continued efforts must be made to ensure all fisheries are monitored and effectively managed, not only the most commercially valuable ones.

4.5 Pillar 3 – Business development services in the Caribbean and Americas fisheries

4.5.1 Caribbean

Digitalisation within the Caribbean’s fisheries sector is hindered by limited business development services. Firstly, there is limited financial investment within the fisheries sector in general, which consequently has a negative impact on potential investments relating to digitalisation. Limited investment is not unique to the Caribbean’s fisheries sector. In fact, the Caribbean’s “Blue Economy” in general is stunted by several challenges, including limited scope for debt finance, restricted fiscal space and declining aid flows. As a result, advancing the Blue Economy and digitalisation will likely require investment in infrastructure, conservation, research and development, institutional and human capacity development, as well as information sharing and knowledge building.[33] Governments within the region are, however, now focusing on digital transformation drives, which in turn should present new opportunities to leverage common infrastructure, procedures and policies for the benefit of fisheries digitalisation. There is also now financial support specifically for fishers being developed and offered within the Caribbean.

For example, in March 2020, the CRFM announced a new $46 million USD initiative to promote Blue Economic priorities in the Caribbean. The initiative, entitled “Blue Economy Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Plus (CLME+): Promoting National Blue Economy Priorities through Marine Spatial Planning in the Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Plus”, is a four-year project supported by funding from the Global Environment Facility through a $6.2 million USD grant and co-financing of $40.1 million.[34] The lead implementing agency of the initiative is the Development Bank of Latin America, while the FAO is acting as a co-implementing agency. The project aims to promote the development of the Caribbean’s blue economy through marine spatial planning and marine protected areas, the ecosystem approach to fisheries and the development of sustainable fisheries value chains.[35]

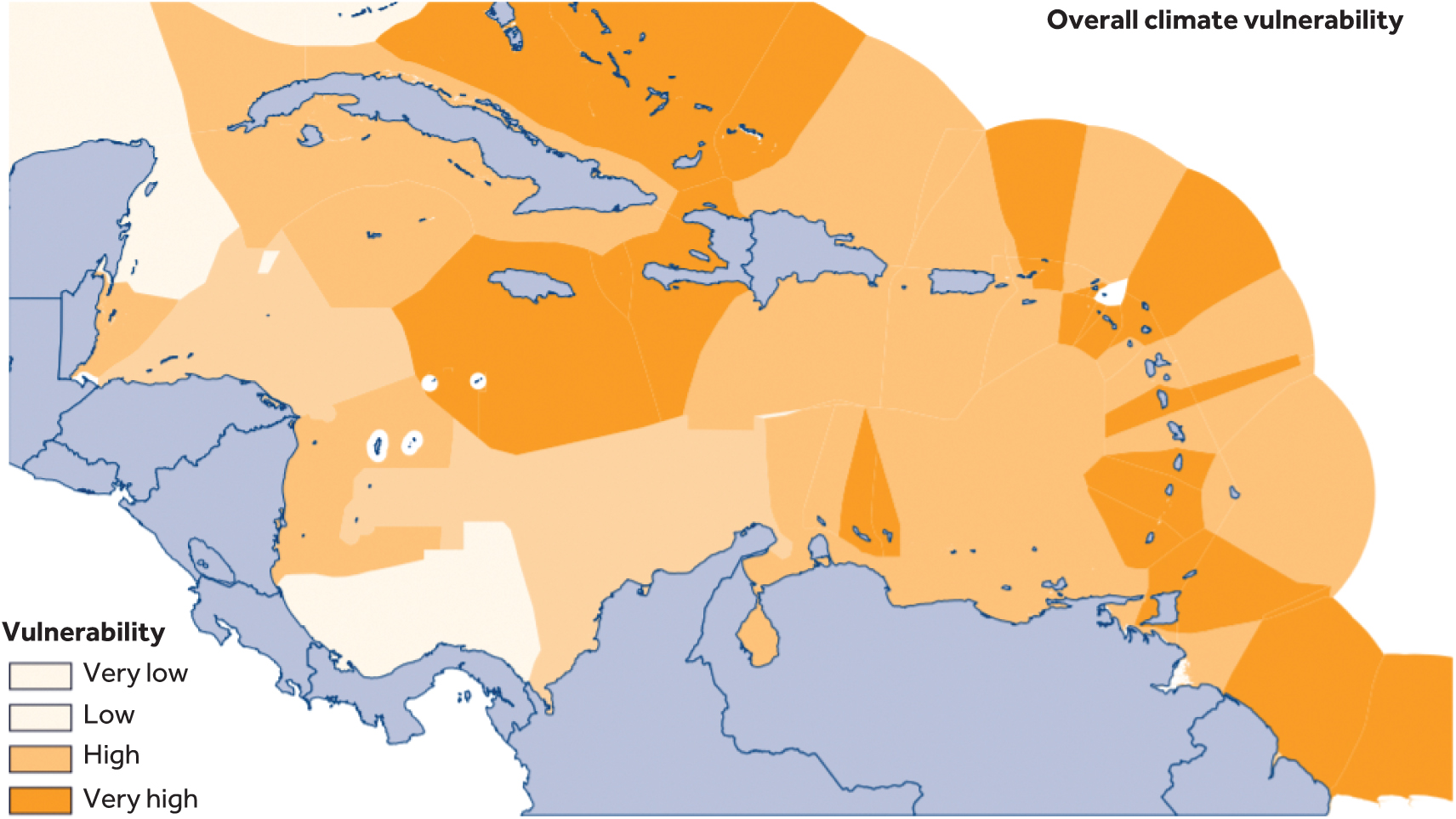

Other ongoing works within the sector aim to aid the sector in response to extreme weather. Much of the Caribbean suffers at the hands of the Atlantic Hurricane season (Figure 4.5), which brings with it tropical cyclones that cause damage and affect the livelihoods of many vulnerable groups including fisheries communities. The economic costs of climate change inaction in the Caribbean are projected to total of $10.7 USD per year by 2025.[36] Impacts felt by fishing communities in the wake of an extreme weather event include loss of productive assets, such as boats, fishing gear and ice facilities, as well as reductions in the coverage and quality of public services such as electricity, fuelling stations, piers and roads. Many fishers do not have finances to recover from such an event and thus cannot fish.[37] To aid fishers in recovering after a natural disaster, the “Caribbean Oceans and Aquaculture Sustainability Facility” (COAST) has introduced a parametric insurance product specifically for the fishers of the Caribbean.[38]

Figure 4.5: Overall climate vulnerability in the Caribbean region calculated as a function of climate exposure or hazard, ecological sensitivity, fisheries sustainability, adaptive capacity.

Source:https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/974010/Climate_Change_Adaptation_for_Caribbean_Fisheries.pdf [accessed” 29/09/2021]

COAST was initially launched for the 2019/20 policy year as a pilot in Grenada and Saint Lucia and received financial support from the US Department of State, the World Bank, the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF SPC) and the CRFM with the aim of enhancing resilience against the impacts of climate-related disasters.[39] The insurance product has been designed to provide fast pay-outs to fishers within 14 days of an extreme weather event. The COAST system is unique in that although it is the government who purchases the insurance policy, the financial beneficiaries are fishers and others associated with the sector, such as fish vendors. The system also actively encourages the involvement of women.[40]

There is also ongoing work within the Caribbean fisheries sector led by the Caribbean ICT Research Programme (CIRP), which aims to build ICT capacity within the region’s SSF. Their ICT stewardship initiative was initiated under the Climate Change Adaptation in the Eastern Caribbean Fisheries Sector (CC4FISH) project which received funding from the FAO with the Global Environment Facility/Special Climate Change Fund being invoked as a resource partner.[41]

CIRP offers training to fishers through various means, such as workshops. For example, in September 2020, a 2-day training course was funded by Climate Change Adaptation in the Eastern Caribbean fisheries sector project (CC4Fish) of the FAO to improve SSF safety at sea through the use of very high-frequency (VHF) radio, GPS and mobile phones.[42] Continued efforts to invest in the sector and improve the financial stability of the Caribbean’s fishers will, in turn, likely lead to move investment in digitalisation and modernisation within the sector.

4.5.2 Canada

Prior to 2019, Canada’s fisheries were managed under legislation that was 151 years old. In June 2019, an amended Fisheries Act was put in place to modernise Canada’s fisheries management to rebuild depleted fish stocks and incorporate local indigenous knowledge. The new Fisheries Act brought with it aid for SSF and businesses through its policies for owner-operator fishers which prevent corporate control of licences and the vertical integration of fish companies. This policy aims to protect the around 10,000 individual fishers working within Atlantic Canada alone as vessel owners are able to operate the ship as well as control the licenses, which enables coastal communities to protect their rights and access to fish.[43]

2019 also saw the Canadian Government announce more than $1.5 million funding from the Fisheries and Aquaculture Clean Technology Adoption Programme (FACTAP) to support clean economic growth in Atlantic Canada. The FACTAP aims to help fisheries and aquaculture business adopt more environmentally friendly practices to improve efficiency, reduce waste and reduce carbon emissions. Investing in new green technology and supporting more sustainable fisheries within the sector in turn aids businesses in remaining competitive in global markets that are becoming increasingly focused on sustainability.[44]

More recently, July 2021 saw the Canadian Government announce that there would be dramatic cutbacks on commercial fishing pressures through the closures of 79 of the country’s 138 fisheries in response to decreasing Pacific salmon runs. The commercial closure came with the promise of a “fishing license buyback programme”, which is due to launch in Autumn 2021. The buyback initiative has been conceptualised in response to years of requests for assistance from fishers, and it is hoped that implementing a smaller nationwide fishery will make it more sustainable in the long term.[45]

4.6 The base – Enabling environments for digitalisation in the Caribbean and Americas fisheries

4.6.1 Caribbean

The enabling environment for fisheries digitalisation in the Caribbean is well developed in terms of the determination of functions needed in the region. The actual implementation is, however, still lacking. Caribbean governments are now beginning a more focused digital transformation drive, and there are plans to increase possibilities to leverage common infrastructure. In addition to the specific digitalisation drive, governments are also increasingly demanding structured data collection and reporting, which will likely form an important foundation upon which future technologies and innovations will be developed. An increasing push for the result-based management will also likely help pave the way to the practical implementation of digitalisation within the region. The main limitations within the Caribbean region are, however, the lack of awareness and understanding of the benefits of digitalisation amongst fishers and the currently disparate efforts and initiatives related to funding digitalisation. Currently, these efforts are being undertaken by numerous agencies that do not actively collaborate.

4.6.2 Canada

Canada has a considerable top-down-based enabling environment which revolves around the governments DFO. The government has numerous policies and strategy-type documents for digitalisation[46] that highlight a clear drive and awareness of the utility of digital technology and innovation. However, few mention fisheries or the maritime sector. This general (non-fisheries) digitalisation is a useful start to later focus efforts for fisheries, but, still to date, no clear implementation of digitalisation in the country’s fisheries appears to exist. This is perhaps not surprising when considering the aging fleet and only recent modernisation efforts through the fisheries act[47] which is still argued to be struggling to manage its stock sustainably.[48]

The Canadian government is considered a leader regarding the release of data and data sharing;[49] however, the data guidelines for fisheries focus on protecting and managing Canada’s aquatic resources and do not talk about digitalisation or technological innovation. The recent improvements in policy and commitments towards greater transparency have started to lead to improvements in data infrastructure, which may eventually pave the way to improved fisheries digitalisation. COVID-19 has been a catalyst that has spurred significant movement regarding inclusivity and support of the Canadian SSF,[50] a welcome relief to many in a country that has largely design its policy and funding arrangements around the LSF sector.

Canada does not suffer from many of the common potential hurdles in its enabling environment (it has good levels of education, a developed fisheries sector, wide-scale data collection processes and good infrastructure), but when it comes to fisheries digitalisation, it shows very little sign of anything outside of government-driven programmes in fisheries digitalisation (no significant private business entrepreneurism in fisheries other than some satellite technologies used for enhanced MCS capabilities). The apparently slow investment in digitalisation may be due to a prioritisation towards more traditional methods of fisheries management focused on stock sustainability and the fact that many areas that warrant investment in other Commonwealth regions, like personal safety, are already well covered across Canada. There is, however, likely still significant space and scope for improvement regarding marginalised and underdeveloped fisheries sectors such as the indigenous tribal fisheries.

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆

[1] Keeping the fishing industry alive calls for new practices | Ministry of Agriculture (2019) https://agriculture.gov.gy/2019/07/06/keeping-the-fishing-industry-alive-calls-for-new-practices/

[2] FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – Belize. Fisheries and Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles - Belize (fao.org)

[3] FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Co-operative Republic of Guyana. Fisheries and Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles - Guyana (fao.org)

[4] LOPRESPUB (2020) ‘Statistics for Canada’s 2018 Commercial Fisheries’. HillNotes. https://hillnotes.ca/2020/06/01/statistics-for-canadas-2018-commercial-fisheries/

[5] LOPRESPUB (2020) ‘Statistics for Canada’s 2018 Commercial Fisheries’. HillNotes. https://hillnotes.ca/2020/06/01/statistics-for-canadas-2018-commercial-fisheries/

[6] About. Assembly of First Nations Fisheries. http://fisheries.afn.ca/learn-more/

[7] TheFutureEconomy.ca (2020) Canadian Fisheries Industry Direction – Carey Bonnell. https://thefutureeconomy.ca/interviews/carey-bonnell/

[8] Government of Canada, S. C. (2021) ‘Measuring digital intensity in the Canadian economy’. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2021002/article/00003-eng.htm

[9] News, A. B. C. (2021) ‘Eastern Caribbean dollar goes digital, a help for unbanked’. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/eastern-caribbean-dollar-digital-unbanked-76819370

[10] News, A. B. C. (2021) ‘Eastern Caribbean dollar goes digital, a help for unbanked’. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/eastern-caribbean-dollar-digital-unbanked-76819370

[11] WorldFish (2020) Information and Communication Technologies for Small-Scale Fisheries (ICT4SSF) – A Handbook for Fisheries Stakeholders. FAO. doi: 10.4060/cb2030en.

[12] FEWER: The app making fisherfolk more secure | PPCR Project (2020) https://caribppcr.org.jm/fewer-the-app-making-fisherfolk-more-secure/

[13] FEWER: The app making fisherfolk more secure | PPCR Project (2020) https://caribppcr.org.jm/fewer-the-app-making-fisherfolk-more-secure/

[14] FEWER: The app making fisherfolk more secure | PPCR Project (2020) https://caribppcr.org.jm/fewer-the-app-making-fisherfolk-more-secure/

[15] Cusack, C. MAnglani, O., Jud, S., Westfall, K., Fujita, R., Sarto, N., Brittingham, P., and McGonigal, H. (2021) ‘New and Emerging Technologies for Sustainable Fisheries: A Comprehensive Landscape Analysis’, 62.

[16] Water-landing drones routinely fly BVLOS missions over marine reserve against illegal fishing and pro-biodiversity (2019) sUAS News – The Business of Drones. https://www.suasnews.com/2019/08/water-landing-drones-routinely-fly-bvlos-missions-over-marine-reserve-against-illegal-fishing-and-pro-biodiversity/

[17] TheFutureEconomy.ca (2020) Canadian Fisheries Industry Direction – Carey Bonnell. https://thefutureeconomy.ca/interviews/carey-bonnell/

[18] Michelin, M., M. Elliott, M. Bucher, M. Zimring and M. Sweeney (2018) Catalyzing the Growth of Electronic Monitoring in Fisheries. https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/Catalyzing_Growth_of_Electronic_Monitoring_in_Fisheries_9-10-2018.pdf

[19] Michelin, M. and M. Zimring (2020) Catalyzing the Growth of Electronic Monitoring in Fisheries. https://fisheriesem.com/pdf/Catalyzing-EM-2020report.pdf

[20] Canada, F. and O. (DFO) (2021) ‘Government of Canada launches international program to track illegal fishing using satellite technology’. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/government-of-canada-launches-international-program-to-track-illegal-fishing-using-satellite-technology-885586184.html

[21] Canada, F. and O. (DFO) (2021) ‘Government of Canada launches international program to track illegal fishing using satellite technology’. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/government-of-canada-launches-international-program-to-track-illegal-fishing-using-satellite-technology-885586184.html

[22] Climate-Smart Fisheries Monitoring and Management Framework for the Caribbean. ESSA. https://essa.com/explore-essa/projects/climate-smart-fisheries-monitoring-and-management-framework-for-the-caribbean/.

[23] Government of Canada, F. and O. C. (2020) ‘Fisheries and Oceans Canada Programs’. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/mtb-ctm/2019/binder-cahier-1/1A2-dfo-programs-mpo-programmes-eng.htm

[24] Government of Canada, F. and O. C. (2020) ‘Fisheries and Oceans Canada Programs’. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/mtb-ctm/2019/binder-cahier-1/1A2-dfo-programs-mpo-programmes-eng.htm

[25] Government of Canada, F. and O. C. (2019) ‘Fishery Monitoring Policy’. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/reports-rapports/regs/sff-cpd/fishery-monitoring-surveillance-des-peches-eng.htm#toc6-3

[26] Archibald, D.W., R. McIver and R. Rangeley (2021) ‘The Implementation Gap in Canadian Fishery Policy: Fisheries Rebuilding and Sustainability at Risk’. Marine Policy 129, 104490.

[27] Archibald, D.W., R. McIver and R. Rangeley (2021) ‘The Implementation Gap in Canadian Fishery Policy: Fisheries Rebuilding and Sustainability at Risk’. Marine Policy 129, 104490.

[28] Atlas, W.I. Ban, N.C., Moore, J.W., Tuohy, A.M., Greening, S., Reid, A.J., Morven, N., White, E., Housty, W.G., Housty, J.A., Service, C.N., Greba, L., Harrison, S., Sharpe, C., Butts, K.I.R., Shepert, W.M., Sweeney-Bergen, E., Macintyre, D., Sloat, M.R., and Connors, K. (2021) ‘Indigenous Systems of Management for Culturally and Ecologically Resilient Pacific Salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) Fisheries’. BioScience 71, 186–204.

[29] News, M. F.-A. | & May 26th 2021, F. I. |. Indigenous Knowledge to Help Identify Sustainable Arctic Fish (2021) Canada’s National Observer. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2021/05/26/news/indigenous-knowledge-help-identify-sustainable-arctic-fish

[30] Andrew, N.L. Béné, C., Hall, S.J., Allison, E.H., Heck, S., Ratner, B.D. (2007) ‘Diagnosis and Management of Small-Scale Fisheries in Developing Countries’. Fish and Fisheries 8, 227–240.

[31] Harper, S. Salomon, A.K., Newell, D., Waterfall, P.H., Brown, K., Harris, L.M., and Sumaila, U. R. (2018) ‘Indigenous Women Respond to Fisheries Conflict and Catalyze Change in Governance on Canada’s Pacific Coast’. Maritime Studies 17, 189–198.

[32] News, M. F.-A. | & May 26th 2021, F. I. |. Indigenous Knowledge to Help Identify Sustainable Arctic Fish (2021) Canada’s National Observer. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2021/05/26/news/indigenous-knowledge-help-identify-sustainable-arctic-fish

[33] Caribbean Development Bank (2018) ‘Financing the Blue Economy: A Caribbean Development Opportunity’. Issuu. https://issuu.com/caribank/docs/financing_the_blue_economy-_a_carib

[34] New GEF-Funded Blue Economy Initiative begins in Caribbean (2020) CARICOM Today. https://today.caricom.org/2020/03/05/new-gef-funded-blue-economy-initiative-begins-in-caribbean/

[35] New GEF-Funded Blue Economy Initiative begins in Caribbean (2020) CARICOM Today. https://today.caricom.org/2020/03/05/new-gef-funded-blue-economy-initiative-begins-in-caribbean/

[36] Commonwealth Marine & Economies Programme (2021) Climate Change Adaptation for Caribbean Fisheries. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/974010/Climate_Change_Adaptation_for_Caribbean_Fisheries.pdf

[37] Innovative Fisheries Insurance Benefits Caribbean Fisherfolk (2019) World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/09/20/innovative-fisheries-insurance-benefits-caribbean-fisherfolk

[38] The Caribbean Catastrophe Insurance Facility & The World Bank (2019) Caribbean Oceans and Aquaculture Sustainability Facility. https://www.ccrif.org/sites/default/files/publications/CCRIFSPC_COAST_Brochure_July2019.pdf

[39] The Caribbean Catastrophe Insurance Facility & The World Bank (2019) Caribbean Oceans and Aquaculture Sustainability Facility. https://www.ccrif.org/sites/default/files/publications/CCRIFSPC_COAST_Brochure_July2019.pdf

[40] Innovative Fisheries Insurance Benefits Caribbean Fisherfolk (2019) World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/09/20/innovative-fisheries-insurance-benefits-caribbean-fisherfolk

[41] WorldFish (2020) Information and Communication Technologies for Small-Scale Fisheries (ICT4SSF) – A Handbook for Fisheries Stakeholders. FAO. doi: 10.4060/cb2030en.

[42] Fisherfolk sharpen ICT skills to ensure safety at sea | United Nations in Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean. https://easterncaribbean.un.org/en/92256-fisherfolk-sharpen-ict-skills-ensure-safety-sea

[43] Canada’s New Fisheries Act Will Help Ecosystem and People (2019) https://pew.org/2XKmBri

[44] Canada, F. and O. (DFO) (2019) ‘Government of Canada helping fisheries and aquaculture businesses adopt clean technologies’. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/government-of-canada-helping-fisheries-and-aquaculture-businesses-adopt-clean-technologies-806755645.html

[45] Canada Announces Widespread Commercial Fishing Closures (2021) https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/environment-sustainability/canada-announces-widespread-commercial-fishing-closures

[46] Government of Canada, S. C. (2021) ‘Measuring digital intensity in the Canadian economy’. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2021002/article/00003-eng.htm

[47] Government of Canada, F. and O. C. (2019) ‘A Modernized Fisheries Act for Canada’. https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/campaign-campagne/fisheries-act-loi-sur-les-peches/index-eng.html

[48] Archibald, D.W., R. McIver and R. Rangeley (2021) ‘The Implementation Gap in Canadian Fishery Policy: Fisheries Rebuilding and Sustainability at Risk’. Marine Policy 129, 104490.

[49] Roche, D.G. Granados, M., Austin, C.C., Wilson, S., Mitchell, G.M., Smith, P.A., Cooke, S.J., and Bennett, J.R. (2021) ‘Open Government Data and Environmental Science: a Federal Canadian Perspective’. FACETS 5, 942–962.

[50] Small Scale Fisheries Can Have a Big Future in Canada’s Food Systems (2021) https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/april-2021/small-scale-fisheries-can-have-a-big-future-in-canadas-food-systems/

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆