3.0 Commonwealth Asia

3.1 Fisheries profile in Commonwealth Asia

Asia’s fisheries sector is considered “productive”, with South Asia’s annual capture fisheries production at approximately 8.5 million metric tonnes (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Asia’s fishery profile.

|

|

Sector |

Statistic |

|

Total annual production |

Capture fisheries: South Asia only |

8,404,608 tonnes |

|

Inland fisheries |

7.95 million tonnes |

|

|

Aquaculture: South Asia only |

9,733,896 tonnes |

|

|

Sources |

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.FSH.CAPT.MT?locations=8S http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/ca9229en.pdf |

|

|

Contribution to GDP |

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP): South Asia only |

18.24 |

|

Sources |

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.FSH.CAPT.MT?locations=8S |

|

|

Employment |

Fisheries |

30,768,00 |

|

Aquaculture |

19,617,000 |

|

|

Sources |

||

|

Consumption

|

Per capita food fish consumption |

24.1 (kg/year) |

|

Sources |

The Asian Commonwealth fisheries can be loosely divided into South Asia and Southeast Asia. South Asian fisheries are important for the economic development of the region and rural livelihoods.

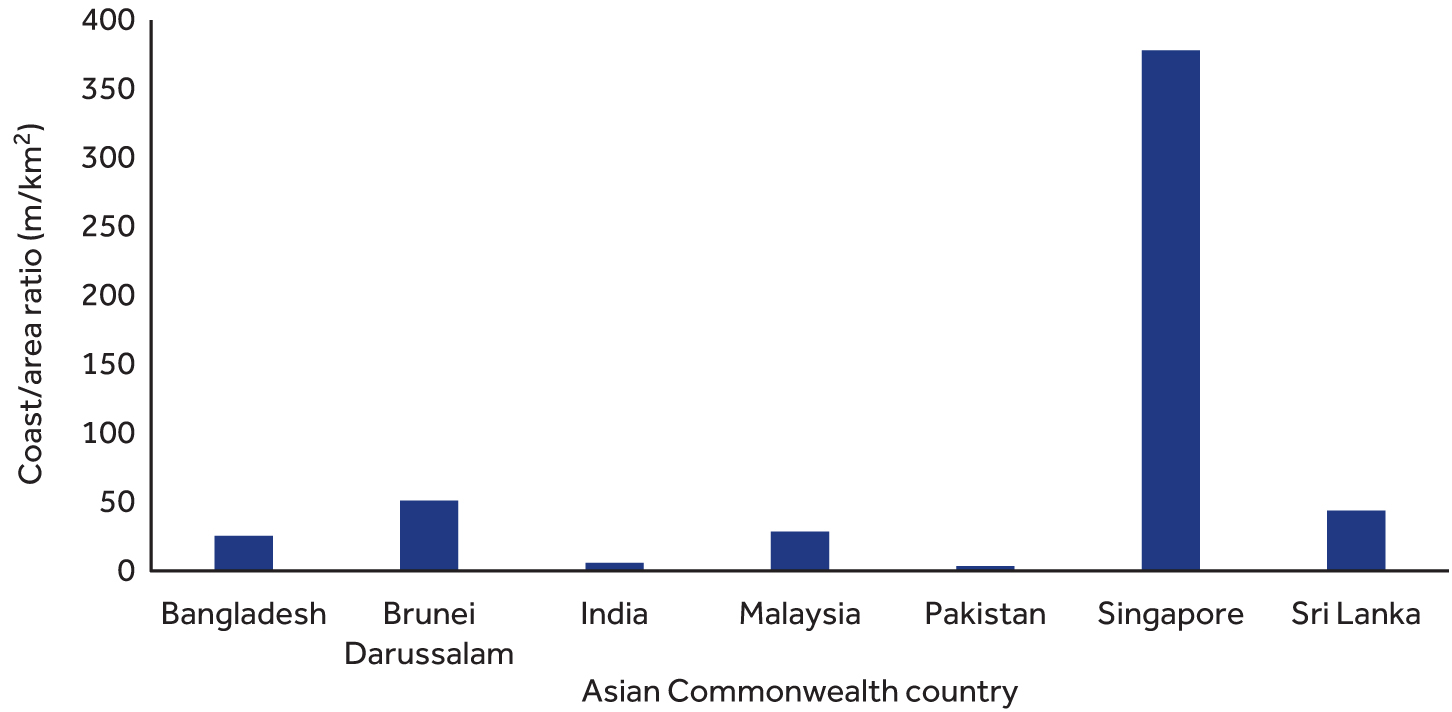

The Asian Commonwealth fisheries can be loosely divided into South Asia and Southeast Asia. South Asian fisheries are important for the economic development of the region and rural livelihoods.[1] South Asian countries (Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) are characterised by long coastlines with extremely high population densities[2] (Figure[ 3.1 and 3.2). Fisheries within the region rely on both inland fisheries, which is the main resource exploited by Bangladesh, and marine fisheries, with India relying heavily on both.[3] Bangladesh is, in fact, considered a global leader in terms of inland fisheries, relying predominantly on freshwater fish species: 1.3 million tonnes compared to 650 thousand tonnes of marine (wild capture) freshwater fish and crustacean species between 2018 and 2019.[4] India, like many other Commonwealth regions, relies predominantly on marine species with an estimated marine fish production of 3.56 million tonnes and 1.6 million tonnes of freshwater species in 2019 alone.[5] One of the most predominant threats faced by fisheries in the South Asia region is that of extreme weather events – predominantly cyclones and floods, which are predicted to increase with the rising temperature of the Indian Ocean[6].

Figure 3.1: Map of Asia showing Commonwealth countries.

Figure 3.2: Coastline to land area ratio for Asian Commonwealth countries.

(Maldives removed for visualization purposes (Maldives ratio is 6,720). In some instances, this ratio can be used as a useful indicator for a country’s reliance on fisheries resources.

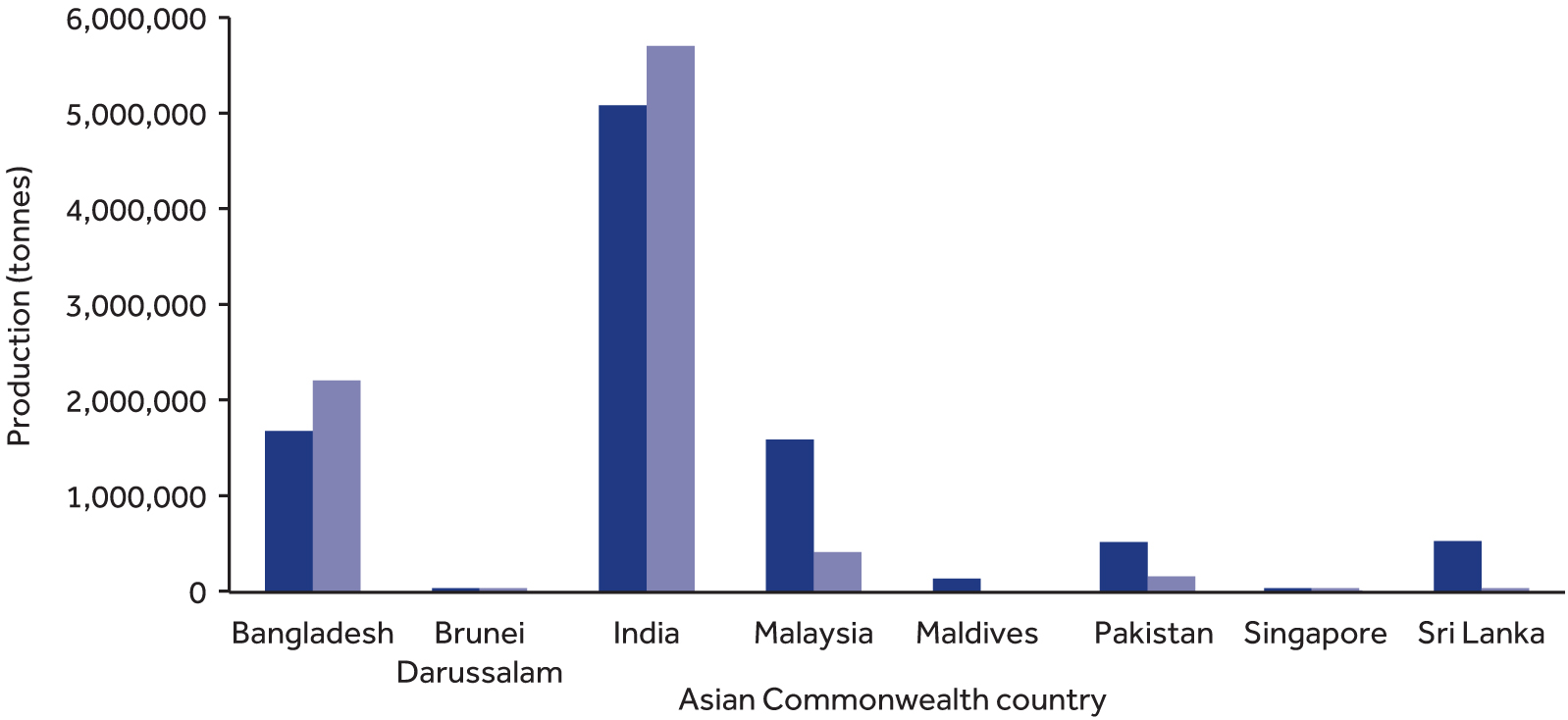

Southeast Asia as a whole produces over 8 million metric tonnes live weight of marine fish, which is around 10 per cent of the global total catch[7] (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3: Capture fisheries and aquaculture production for the Asian Commonwealth countries.

Blue bars = fisheries, orange bars = aquaculture Source: World Bank (2018-2019).

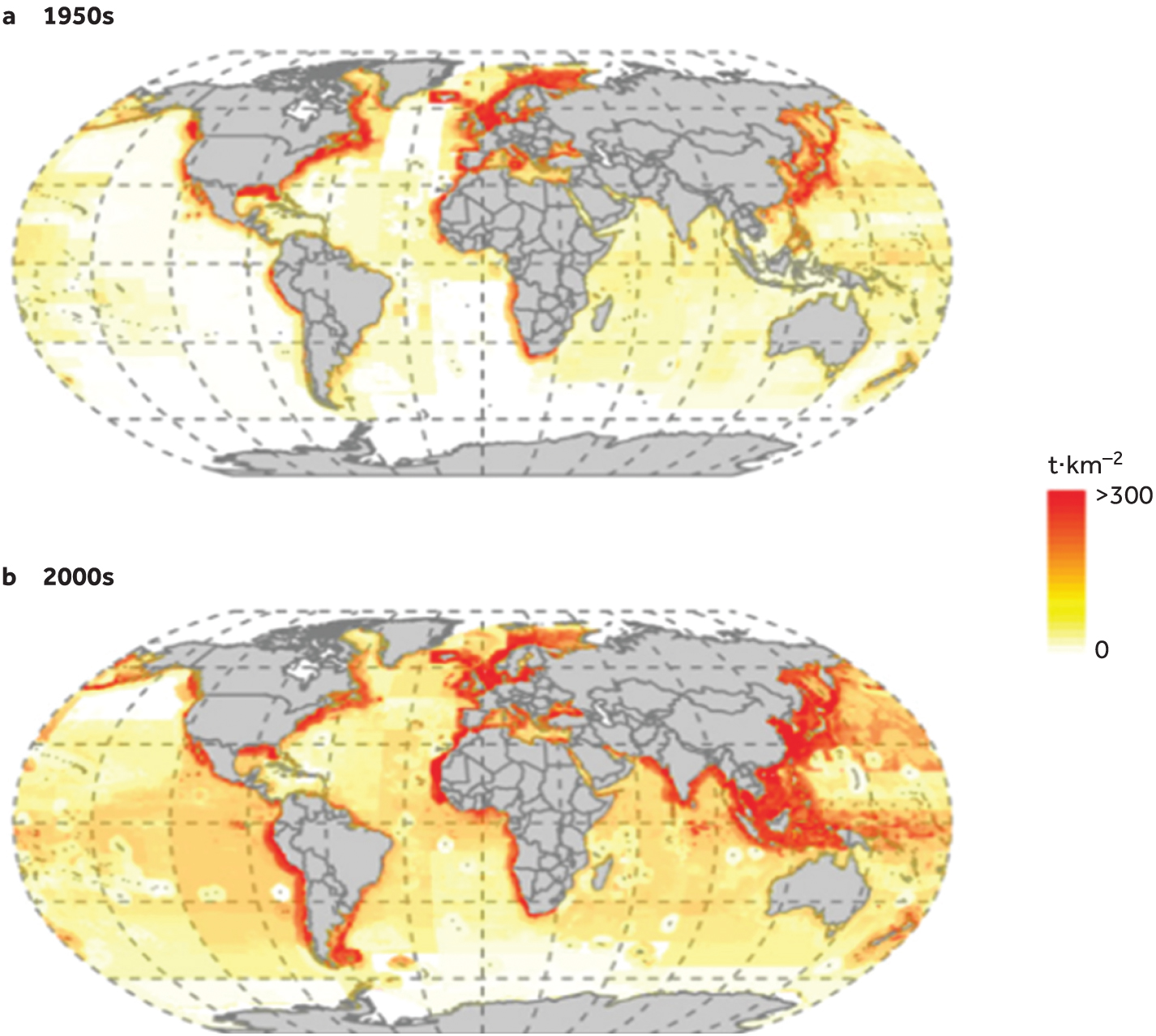

Malaysia boasts substantial marine fisheries resources, producing 1.5 million tonnes from capture fisheries in 2019.[8] Brunei and Singapore have comparatively limited marine fisheries captures and resources in general.[9] Fisheries production in Singapore is mainly sourced from small aquaculture enterprises with only a small quantity coming from local capture fisheries.[10] In general, fisheries pressures in the Southeast Asia region have increased significantly in recent decades (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4: Mean industrial fisheries catch in tonnes per square kilometre by catch location during the (A) 1950s and (B) 2000s.

Source: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aar3279 [accessed 29/09/2021]

3.2 Digitalisation in Asian fisheries

Asia’s fisheries sector predominantly revolves around SSF, and there is a heavy regional reliance on fisheries for nutrition and livelihoods. As such, many of Asia’s coastal fisheries are under pressure. Digitalisation within the sector represents an opportunity to improve current fisheries management practices and thus improve local fisheries sustainability, food security and the well-being of fishing communities.[11] Current management in the region, however, generally lacks appropriate frameworks to support the adoption of digitalisation. Currently, there are common trends that tend towards exclusivity, particularly for lower income fishers and women working within the sector. Therefore, another important challenge is ensuring digitalisation within the region is inclusive.

3.3 Pillar 1 – Digital innovations in Asian fisheries

3.3.1 Digital technologies

Most digital innovations within Asia’s fisheries sector are in the research, development and formation stages, with few in the implementation or operational phases. Although there are lots of digital innovations available, uptake is vastly hindered due to poor network coverage in coastal areas. For example, despite there being good levels of weather information available to fishers in India, there is a gap between what is available and what is adopted. This is largely due to the lack of cellular coverage at sea which generally reaches a maximum distance of between 8 and 20 km from the coastline. This prevents fishers from accessing real-time information when in remote areas or too far offshore.

Despite digital fisheries solutions and services in Asia being widely nascent, India is regarded as a hotspot of innovation. One such example is the Indian Space Research Organisation’s (ISRO) “Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System” initiative, known as “NavIC”. NavIC was designed and developed to create an independent satellite-based navigation system to provide positioning, navigation, and timing services for users throughout India and to increase connectivity.[12] The NavIC system uses a constellation of seven satellites to produce a navigation system able to provide a position accuracy of better than 10 m up to 1500 km offshore.[13]

Although the use of satellites offers the fisheries sectors many solutions to current challenges, there are numerous issues associated with the uptake of digitalisation that rely on them. Using satellites is extremely expensive, and so even when trials prove the utility of a technology that uses satellite-based connectivity, long-term use is often short lived once initial funding periods end. A large pilot run in India, which created 120 km of cellular coverage at sea using satellites, demonstrates this well as the successful and this trial was ended after just 2 years due to the associated costs.

3.3.2 Digital solutions and services

Following the implementation of the NavIC system, an app was developed for use by fishers, so they could benefit from the system simply by using a compact NavIC device onboard that connects to the fisher’s smartphone via Bluetooth. The app, which is available in 13 different regional languages,[14] allows fishers access to positioning information for navigation, alert messages on rough seas, weather information and warning messages when approaching international water boundaries. The app also provides fishers with a communication service, which allows for messages to be exchanged both between fishers and boat owners.[15] Access to these services significantly improves safety onboard fishing vessels. As of March 2020, the ISRO had distributed around 250 NavIC units to the State Fisheries Department of Kerala and Tamil Nadu for use by local fishers. Elsewhere, the Department of Fisheries of Tamil Nadu reported that 200 NavIC units have been provided to “80 clusters”, each with 10–15 deep sea fishing boats.[16]

Satellite technology is also being used within the fisheries sector in the Maldives. In October 2020, Inmarsat and Cobham SATCOM was awarded a new contract to connect 732 fishing vessels operating in the Maldives EEZ to Inmarsat’s “Fleet One” maritime broadband services. Fleet One uses an existing satellite constellation to facilitate reliable global voice calling and Internet connectivity through a compact, lightweight antenna and a simple installation process. The technology is said to be affordable, as well as small in size, and thus more accessible to SSF, which previously may not have had access to maritime satellite communication.[17] As well as improving safety at sea, Fleet One offers electronic catch documentation and traceability (eCDT) to aid the fight against IUU fisheries and a VMS platform to monitor fishing vessel movements. If rolled out across the whole of the Maldivian fleet, the Fleet One project would see the Maldives fulfil (and go beyond) the requirements of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission.[18]

Satellite-based IoT technology firm “Skylo Technologies” are also utilising technology to offer fishers a solution to improve fishers safety while at sea. August 2021 saw Skylo announce a partnership with India’s National Federation of Fishers Cooperatives Ltd. (FISHCOPFED) to bring IoT-based solutions to the fisheries and aquaculture sector.[19] Through this partnership, Skylo and FISHCOPFED aim to improve the welfare of fisherman and fish farmers through their “advanced solutions” which include two-way messaging services, SOS alerts and fish catch reporting. For the aquaculture sector, their solutions offer sensor integrations for capture of different parameters on the water quality of farmed fish to enable farmers to make immediate and informed decisions. FISHCOPFED states that they will make Skylo’s cost-effective tech solutions available to its 33 lakh fishers members, thus bringing digitalisation to small-scale fishers and fish farmers in India.[20]

Skylo seems to have overcome the high price tag associated with the use of satellite connectivity claiming to be “disruptively affordable”, costing 95 per cent less than today’s satellite connectivity. Associated costs are less than $100 for an 8″×8″ transceiver/hub and as low as $1/month for connectivity.[21] Skylo is also the first company to leverage the cellular Narrowband IoTs protocol for satellite communications.[22] Outside of fisheries, Skylo partnered with “BSNL”, India’s government-owned telecommunications provider, to develop the “Made in India” solution, which connects with NSNLs satellite-ground infrastructure and provides PAN-India coverage with no “dark patches” across the boundary of India from Kashmir and Ladakh to Kanyakumari, and from Gujarat to the Northeast, including the Indian seas.[23]

3.4 Pillar 2 – Data Infrastructure in Asian fisheries

Generally, the fisheries data infrastructure across Asia is considered poor. While most Asian countries have some level of data reporting and data generating infrastructure, a significant amount of data collection is still undertaken using paper and relies on manual data entry and analysis. Despite more recent advances and improvements in the data infrastructure surrounding Asia’s LSF (in terms of vessel positioning and catch data), data scarcity, particularly relating to spatio-temporal trends in catch and effort, is common particularly in Asia’s SSF.[24] In Southeast Asia, for example, SSF fleets often operate entirely unmonitored, and many contain little to no electronic technologies onboard, highlighting the simplicity of many of these SSF operations. This has negative implications for both target and non-target species and the wider marine ecosystem as well as the personal safety of fishers whilst at sea.[25]

The availability of quality catch data is a limiting factor in the digitalisation of Asia’s fisheries. Many digital solutions lack the data sets necessary to move beyond descriptive analyses towards predictive and prescriptive analyses. Collecting reliable fisheries data is additionally difficult in this region which boasts over 12,000 species of seafood products, making species identification an additional hurdle. Common names also vary across the region, and different species may be referred to by different names depending on their life phase, compounding this difficulty. A study conducted by TNC in Indonesia found that over 50 per cent of landed species were being misidentified.[26] To address this common problem, extensive awareness-raising and collaborative exercises promoting the benefits of standardised data collection are required.

Data pertaining to Asian fisheries, as in many other regions, is collected and owned predominantly by governments. There are, however, efforts driven by non-governmental organisations and civil society organisations across the region to innovate and change this top-down model towards a more collaborative process. Implementation of an intergovernmental platform for fisheries data would be highly beneficial for commercial solutions to utilise and build out from; however, such a platform is (at present) unlikely given the geopolitics surrounding fisheries.[27] A first positive step would therefore be for data sharing platforms that foster government-industry collaboration to be created at national levels.

One recent example of a non-government-funded innovation is “Fish Nutrients”,[28] a new open-source tool that places fish nutrient data at the fingertips of researchers, policy makers and the general public. The aim of this tool is to guide nutrition-sensitive approaches to fisheries management that aim to improve consumption of nutrient-rich species in malnourished communities. Fish nutrients combine two important aspects of data innovation. The first is the storage and presentation of large multinational datasets made available to broad audiences. The second is the behinds the scenes use and processing of the data that is formed based on species-specific predictions of nutrient composition of finfish globally. The new methods actually bolt-on to an existing platform “FishBase” (the world’s largest encyclopaedia of fish),[29] highlighting the somewhat rarer case in which a new innovation builds on existing infrastructure and knowledge. This may help reduce early failure risks in the platform and also help maintain successful funding of the platform for future updates and design iterations.

Key challenges standing in the way of modernising fisheries data infrastructure in Asia include inadequate funds to acquire the hardware and software necessary to modernise. Although investment in modernising fisheries data systems can produce potential long-term savings by making fisheries operations more efficient and safeguarding stocks for future generations, the cost of switching to new technology, and the infrastructures and human resources that go with it, is often high. Many fishers feel that information technology installation is too expensive, especially within low-income SSF.[30] For example, in India, fisheries-related information services were rolled out to fishers under a paid subscription. Although the product allowed fishers to optimise their catch and fish less days, the price of fish did not change, and thus, subscriptions fell. The fishers felt that since the use of this data allowed them to fish less days and thus perform better for both themselves and the environment, they should have been granted access for free.[31]

A second challenge in data infrastructure modernisation across Asia is the lack of confidence that the fishing industry has in information technologies, especially in cases where available solutions are complicated and difficult to use. For example, in India, efforts to implement boat tracking systems were initially poorly accepted by fishers even though they were beneficial for safety at sea and security purposes, although adoption is now slowly increasing, especially for security purposes.

To address low acceptance and subsequent adoption, there should be extensive awareness raising and collaborative exercises conducted to improve knowledge within the sector about the need for data collection and its benefits. This will also help avoid situations in which fishers view digitalisation and data collection efforts as surveillance exercises that will jeopardise their livelihoods over the long-term from more stringent management based on better knowledge of current fishery impacts. Furthermore, implementation barriers often arise from long drawn legal and bureaucratic processes which lead to implementation delays. This in turn slows down adoption of new technologies. There is also a lack of data collection standards within Asia’s fisheries that lead to inconsistencies in data collection efforts. These inconsistencies will continue to hinder initiatives to improve data collection and the interpretation of data, thus preventing its effective long-term use.[32]

The fisheries sector within Asia is also facing difficulties due to limited financial inclusion. As many fishers have a fluctuating income, they are not able to access financial services, such as loans, through banks directly without additional help. In Sri Lanka, where most fishers are individual or informal workers, fishers are excluded from the financial sector due to a lack of digital identity and inability to provide a history of financial data. This prevents them from accessing formal financial services offered by banks and other professional organisations. Instead, fishers are forced to rely on informal ways of acquiring microloans and microfinancing, which results in a “debt trap”.[33]

The “Mobile for Development Digital Identity” programme aims to enable fishers to formal financial services by creating a digital identity for fishers. This is done through Mobitel’s MCASH platform. Fishers have a mobile number linked to a national identity and have mobile money accounts set up for them. Through mobile money accounts, fishers are then able to verify unique digital identities and demonstrate economic abilities. Fishers are then able to access microloans and other financial services using their digital identities and credit scores.[34] Overall, there is still considerable work to be done to ensure the associated data requirements of the sector are met. This will aid digitalisation efforts and ultimately improve the welfare of fishers in the region and the efficiency of fisheries managers.

3.5 Pillar 3 – Business development services in Asian fisheries

Business development services within Asia’s fisheries sector are generally very limited and suffer from similar issues related to digital innovations and data infrastructure. Somewhat of a charity-like mentality across Asia exists when it comes to the development of new innovations. A mentality that leaves funding up to philanthropy or private business investment rather than government agencies. This means that rather than innovation and entrepreneurship in fisheries digitalisation being actively driven, it is only supported to a limited extent if business models appear to stand up to scrutiny and appear viable for economic returns. This idealism of expecting financial reward from digitalisation innovations may be seen as problematic as it potentially limits blue sky thinking and produces a low-risk enterprise environment which is not conducive to breeding state of the art breakthrough ideas/innovations.

The sector also suffers from exclusion from global markets. For example, Pakistan has been banned from exporting fish to the European Union due to their lack of international standard refrigeration. However, in April 2021, US-based Pakistani engineer named Dr Zahid Ayub of Parachinar unveiled the country’s first ever refrigerated seawater fishing boat. After meeting all international standards and successful trials, the boat has been put into operation at Karachi harbour.[35]

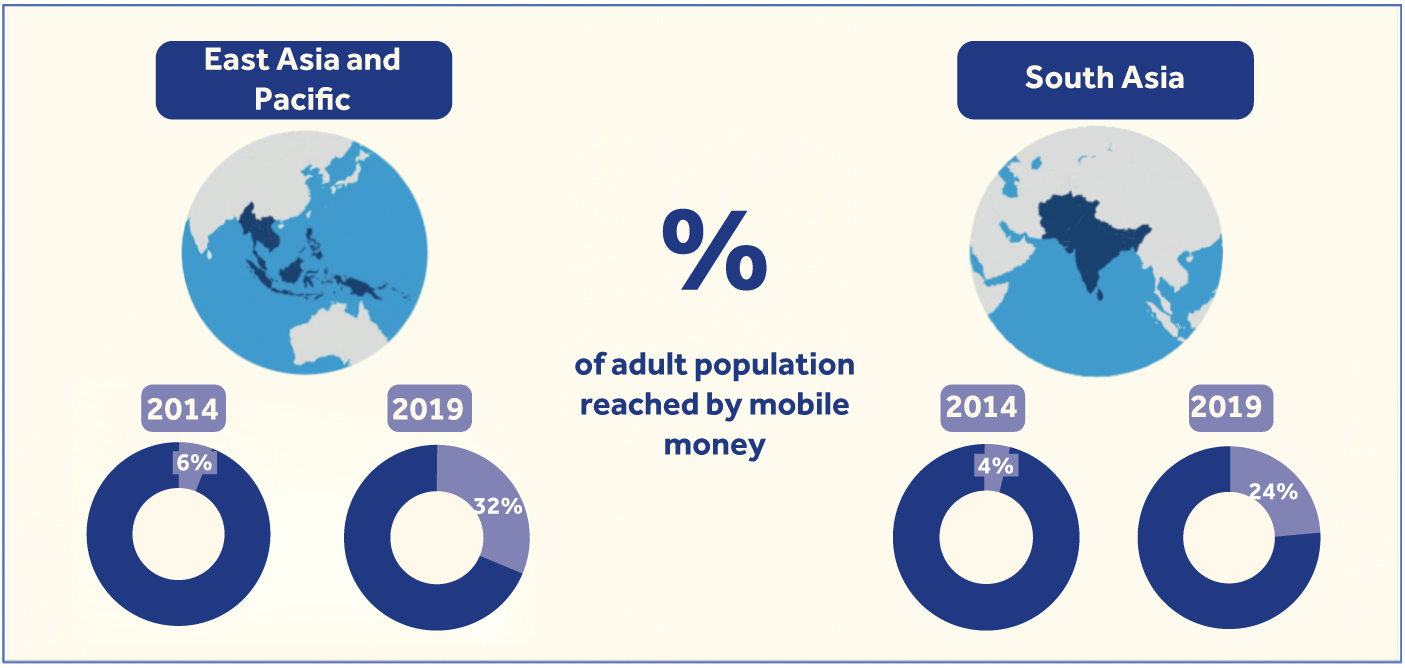

Network penetration and the associated costs of technology and Internet access also limit the scope for business development within much of the Asian fisheries sector. Similarly, there is limited uptake of mobile money and digital wallets required for official identification and financial transaction purposes. Asia accounts for almost half of all registered mobile money accounts globally, with 473 million registered users as of 2019[36] (Figure 3.5). The lack of mobile money transfer technology adoption in Asia’s SSF therefore highlights a potential low hanging fruit.

Figure 3.5: Mobile money use in adults for East Asia Pacific and South Asia.

Source: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-state-of-the-mobile-money-industry-in-Asia-2019-1.pdf [accessed: 29/09/2021]

Funding for digital solutions and technologies within the sector is not considered to be sustainable as there is a heavy reliance on external aid funding in most cases. A mentality that leaves funding up to philanthropy or private business investment rather than government agencies. This means that rather than innovation and entrepreneurship in fisheries digitalisation being actively driven, it is only supported to a limited extent if business models appear to stand up to scrutiny and appear viable for economic returns. This idealism of expecting financial reward from digitalisation innovations may be seen as problematic as it potentially limits blue sky thinking and produces a low-risk enterprise environment which is not conducive to breeding state of the art breakthrough ideas/innovations.

India, however, is considered “progressive” based on its government funding for digital development initiatives and policies that encourage entrepreneurship and private investment within their fisheries sector. For example, in February 2021, the National Fisheries Development Board had opened applications for “Entrepreneur Models in Fisheries & Aquaculture”. Applications are open to individual entrepreneurs and private firms, fishers, fish farmers, fish workers and fish vendors, as well as self-help groups, fisheries cooperatives, joint liability groups and fish farmer producer organisations/companies. The aims of the entrepreneur model include attracting enhanced private investment in the fisheries and aquaculture sector, enhancing production, productivity and profitability across the value chain by achieving economies of scale, encouraging technology uptake and addressing value chain gaps among others.[37]

Efforts are also being made to integrate e-commerce into Asia’s fisheries sector. The “Live from Hilsha Bari” campaign was launched in Bangladesh to connect hilsha fish caught by fishers in the Chandpur River area and consumers. Prospective buyers in Dhaka can purchase hilsha through the shop’s website and app, as well as through sector e-commerce sites Chaldal.com, Evaly, Parmida and Khas Foods.[38] Other e-commerce initiatives such as the Malaysia-based MyFishman (see “COVID-19 – A catalyst of change?” box) are also operating within Asia’s fisheries sector to connect fishers with consumers. E-commerce has not only aided the sector during lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic but also enabled fishers to sell their catch more efficiently and ensures fairer pricing.

Business development within the sector is also reliant on sufficient training to aid fishers in the integration of digital solutions, promoting sustainability and ensuring profitability. In Southeast Asia, the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Centre[39] offers the industry various capacity building programmes.[40] Offered programmes include online practical workshops on the use of the eACDS Application for fisheries officers, fish population dynamics and fisheries management, and the use of deck machineries and hauling devices to reduce manpower in fishing vessels and enhance safety in fishing operations.[41] They also promote offshore fisheries through training on “best practice” and energy optimisation technology with the aim of improving food security and reducing fishing pressures in coastal areas.[42]

3.6 The base – Enabling environments for digitalisation in Asian fisheries

Enabling environments for digitalisation vary across the Asian Commonwealth countries although there are some clear patterns pertinent to all. The main hurdles include connectivity for the use of mobile devices which is still broken and often very poor offshore, the high cost versus low return on investment of digitalisation technologies and a lack of clear standards promoting their uptake.

In some cases, such as Malaysia, there are government efforts to give aid to those within the fisheries sector. Each registered fisherman within Malaysia receives a monthly allowance of ~ RM 300 alongside a daily fuel subsidy of RM 45.[43] The aim of this financial support is to reduce the daily burden of SSFs; however, it is insufficient as the poverty level amongst fishers in Malaysia is high. This is thought to be due to climate change which has reduced the productivity of the sector.[44] As a result, these fishers would benefit greatly from access to GPS, mobile phones and echosounders to improve productivity during fishing activities.[45] Efforts elsewhere within India are more focused on digitalisation.

Specific to the capture fisheries sector is a need for better connectivity when vessels are offshore (30–50 km minimum). Investment in such services would greatly increase the likelihood of uptake of SOS service technologies, business transactions related to live market pricing and sales and general communication for fishers. Improvements in offshore connectivity may also open the door to mariculture opportunities in which IoT sensors can be employed to monitor conditions live in farm operations.

Much of the current hurdles facing digitalisation in Asia’s fisheries sector is a result of the lack of infrastructure which ultimately is determined by investment. Investment in such is usually driven by government (as is largely the case in India), but a lack of prioritisation for the fisheries sector across much of Asia means that government-aided programmes for the infrastructure development to support coastal and offshore connectivity is still lacking (excluding India). Poor government funding may also be blamed for a lack of education in certain parts, which influences the ability of certain technologies to be both used and welcomed in the less-developed SSF sectors. In addition, there are still lack of specific drivers in educational policy to promote gender equality and empowerment and improve the representation of marginalised communities/individuals.

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆

[1] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[2] Hossain, M. and R. Shrestha (2019) ‘Fisheries in South Asia: Trends, Challenges and Policy Implications’, 332–346.

[3] Hossain, M. and R. Shrestha (2019) ‘Fisheries in South Asia: Trends, Challenges and Policy Implications’, 332–346.

[4] Department of Fisheries (2019) Yearbook of Fisheries Statistics of Bangladesh, 2018–19. http://fisheries.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/fisheries.portal.gov.bd/page/4cfbb3cc_c0c4_4f25_be21_b91f84bdc45c/2020-10-20-11-57-8df0b0e26d7d0134ea2c92ac6129702b.pdf

[5] Gopalakrishnan, D.A. (2019) Marine Fish Landings in India 2019. 16.

[6] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[7] Sustainable Fisheries, Environment and the Prospects of Regional Cooperation in Southeast Asia | Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability (2010) https://nautilus.org/eassnet/sustainable-fisheries-environment-and-the-prospects-of-regional-cooperation-in-southeast-asia-2/

[8] Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=72&bul_id=SEUxMEE3VFdBcDJhdUhPZVUxa2pKdz09&menu_id=Z0VTZGU1UHBUT1VJMFlpaXRRR0xpdz09

[9] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[10] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[11] Mozumder, M.M.H. Pyhala, A., Wahab, M.A., Sarkki, S., Schneider, P., Islam, M.M. (2019) ‘Understanding Social-Ecological Challenges of a Small-Scale Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) Fishery in Bangladesh’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, 4814.

[12] IRNSS Programme – ISRO. https://www.isro.gov.in/irnss-programme

[13] Annadurai, M. (2018) Indian Space Programme: Past Pride & Future Challenges. http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/44269/1/SR%2055(5)%2028-32.pdf

[14] Doshi, G.J. (2019) NavIC and MSS based Messaging and Surveillance Applications. https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/icg/2019/icg14/15.pdf

[15] Doshi, G.J. (2019) NavIC and MSS based Messaging and Surveillance Applications. https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/icg/2019/icg14/15.pdf

[16] Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System. https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1606784

[17] ShipInsight (2020) Inmarsat and Cobham SATCOM enable Maldives fisheries sustainability with Fleet One. https://shipinsight.com/articles/inmarsat-and-cobham-satcom-enable-maldives-fisheries-sustainability-with-fleet-one/

[18] Inmarsat Corporate Website (2020) Inmarsat and Cobham SATCOM enable Maldives fisheries sustainability with Fleet One. https://www.inmarsat.com/en/news/latest-news/maritime/2020/inmarsat-and-cobham-satcom-enable-maldives-fisheries-sustainabil.html

[19] Skylo Technologies (2021) Skylo and FISHCOPFED partner to improve fishermen safety, increase catch profitability, and bolster ecosystem sustainability. – Skylo, FISHCOPFED tie up to improve fishermen safety, profitability | Business Standard News (business-standard.com)

[20] Skylo Technologies (2021) Skylo and FISHCOPFED partner to improve fishermen safety, increase catch profitability, and bolster ecosystem sustainability. – Skylo, FISHCOPFED tie up to improve fishermen safety, profitability | Business Standard News (business-standard.com)

[21] Ventures, D.C.M. (2020) ‘Announcing Our Investment in Skylo – The World’s Most Affordable Satellite Technology’. The Global Frontier. https://medium.com/the-global-frontier/announcing-our-investment-in-skylo-the-worlds-most-affordable-satellite-technology-8a9f54623d59

[22] Skylo Technologies (2021) Skylo and FISHCOPFED partner to improve fishermen safety, increase catch profitability, and bolster ecosystem sustainability. – Skylo, FISHCOPFED tie up to improve fishermen safety, profitability | Business Standard News (business-standard.com)

[23] ShipInsight (2020) Inmarsat and Cobham SATCOM enable Maldives fisheries sustainability with Fleet One. https://shipinsight.com/articles/inmarsat-and-cobham-satcom-enable-maldives-fisheries-sustainability-with-fleet-one/

[24] ShipInsight (2020) Inmarsat and Cobham SATCOM enable Maldives fisheries sustainability with Fleet One. https://shipinsight.com/articles/inmarsat-and-cobham-satcom-enable-maldives-fisheries-sustainability-with-fleet-one/

[25] Exeter, O. M., Htut, T., Kerry, C. R., Kyi, M.M., Mizrahi, M., Turner, R.A., Witt, M.J., and Bicknell, A.W.J. (2021) ‘Shining Light on Data-Poor Coastal Fisheries’. Frontiers in Marine Science 7, 1234.

[26] Latumeten, G.A. Septiani, W.D., Godjali, N., Wibisono, E., Mous, P., Pet, J.S. (2018) ‘Training Manual for Identification of 100 Common Species in the Deepwater Hook-and-Line Fisheries Targeting Snappers, Groupers, and Emperors in Indonesia’, 207.

[27] Chaturvedi, A. and P. Basu (2021) ‘In Deep Water: Current Threats to the Marine Ecology of the South China Sea’. ORF. https://www.orfonline.org/research/in-deep-water-current-threats-to-the-marine-ecology-of-the-south-china-sea/

[28] Hicks, C. (2021) FishNutrients: Launching Nutrient Data on Fish in FishBase.

[29] Fish Nutrient Data Platform Tools Up the Fight Against Malnutrition | WorldFish (2021) https://www.worldfishcenter.org/blog/fish-nutrient-data-platform-tools-fight-against-malnutrition

[30] Role of IoT in the Fisheries Sector in India. https://cgglpublic.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/static/Role+of+IoT+in+the+Fisheries+Sector.pdf

[31] Hertzum, M. Singh, V.V., Clemmensen, T., Signh, D., Vatolina, S., Abdelnour-Nocera, J. and Qin, X. (2018) ‘A Mobile App for Supporting Sustainable Fishing Practices in Alibaug’. Interactions 25, 40–45.

[32] Role of IoT in the Fisheries Sector in India. https://cgglpublic.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/static/Role+of+IoT+in+the+Fisheries+Sector.pdf

[33] Financial Inclusion for Fishing Communities Through Digital Identity – Mobitel Sri Lanka (2020) Mobile for Development. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/financial-inclusion-for-fishing-communities-through-digital-identity-mobitel-sri-lanka/

[34] Financial Inclusion for Fishing Communities Through Digital Identity – Mobitel Sri Lanka (2020) Mobile for Development. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/financial-inclusion-for-fishing-communities-through-digital-identity-mobitel-sri-lanka/

[35] Saeed, F. (2021) ‘Pakistan Develops its First Ever Refrigerated Sea Water Fish Boat’. Mashable Pakistan. https://pk.mashable.com/tech/9120/pakistan-develops-its-first-ever-refrigerated-sea-water-fish-boat

[36] GSMA (2019) State of the Mobile Money Industry in Asia. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-state-of-the-mobile-money-industry-in-Asia-2019-1.pdf

[37] National Fisheries Development Board (2021) Entrepreneur Models in Fisheries and Aquacutlure. https://nfdb.gov.in/PDF/N_EM2021.pdf

[38] Tech Observer (2021) Bangladesh: Hilsha fish goes online. https://techobserver.in/2021/09/02/bangladesh-hilsha-fish-goes-online/

[39] SEAFDEC – Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center. http://www.seafdec.org/

[40] Pomeroy, R., J. Parks, K. Courtney and N. Mattich (2016) ‘Improving Marine Fisheries Management in Southeast Asia: Results of a Regional Fisheries Stakeholder Analysis’. Marine Policy 65, 20–29.

[41] Training – SEAFDEC/Training Department. Training. http://www.seafdec.or.th/home/training

[42] Pomeroy, R., J. Parks, K. Courtney and N. Mattich (2016) ‘Improving Marine Fisheries Management in Southeast Asia: Results of a Regional Fisheries Stakeholder Analysis’. Marine Policy 65, 20–29.

[43] Mazuki, R., M.N. Osman, J. Bolong and S.Z. Omar (2020) ‘Systematic Literature Review: Benefits of Fisheries Technology on Small Scale Fishermen’. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 10, 307–316.

[44] Mazuki, R., M.N. Osman, J. Bolong and S.Z. Omar (2020) ‘Systematic Literature Review: Benefits of Fisheries Technology on Small Scale Fishermen’. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 10, 307–316.

[45] Mazuki, R., M.N. Osman, J. Bolong and S.Z. Omar (2020) ‘Systematic Literature Review: Benefits of Fisheries Technology on Small Scale Fishermen’. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 10, 307–316.

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆