2.0 Commonwealth Africa

2.1 Fisheries profile in Commonwealth Africa

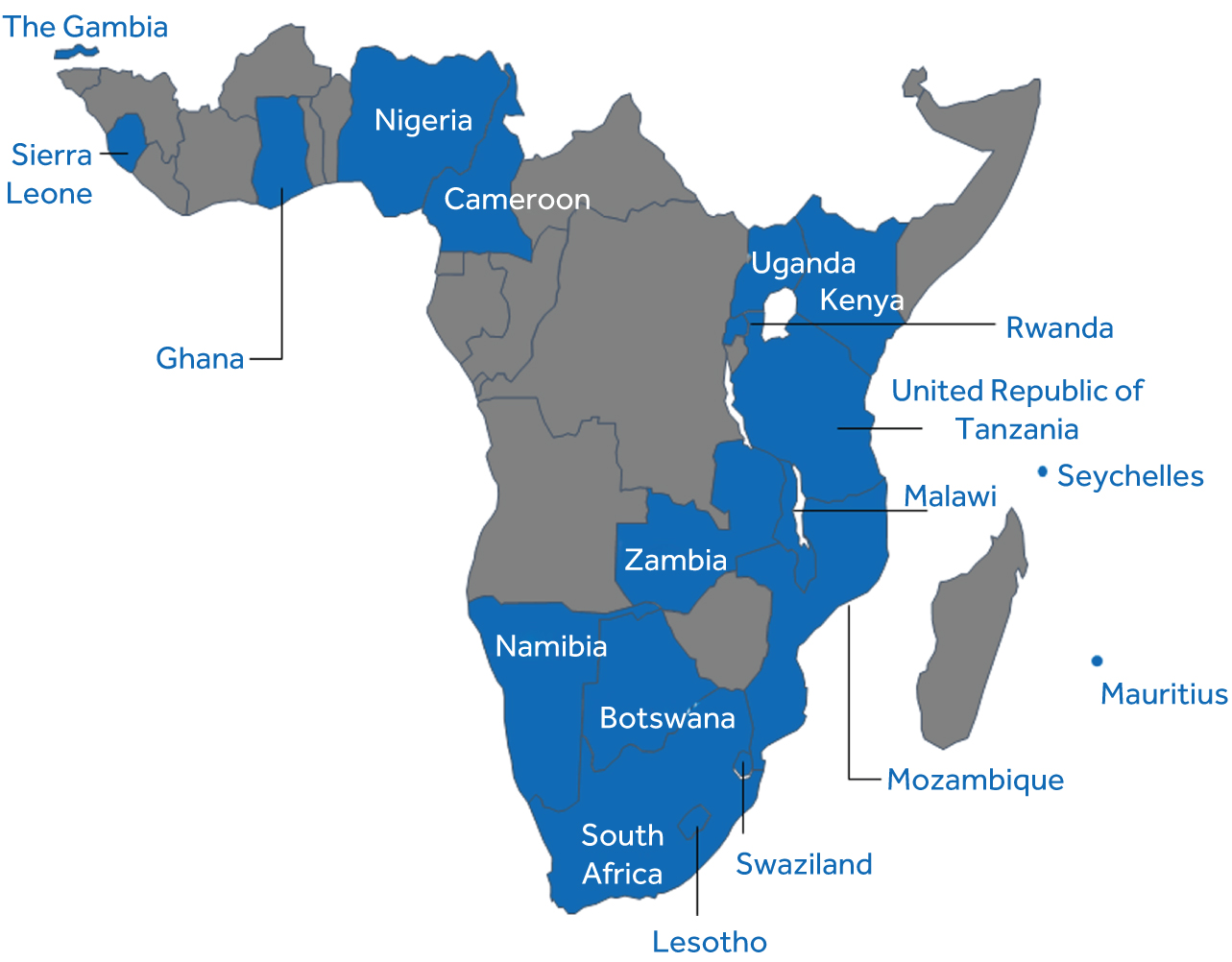

Africa’s marine fisheries produce 6.7 million tonnes of seafood annually and employ 5,210,000 people, while their inland fisheries produce 3.0 million tonnes of fisheries products (Table 2.1). In terms of fisheries characteristics, the African Commonwealth can be broadly divided into the West, East and Southern Cape African Commonwealth (Figure 2.2). In the West African Commonwealth (The Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon), fish accounts for approximately two-thirds of all animal protein consumed.[1]

Table 2.1: Africa’s fishery profile

|

|

Sector |

Statistic |

|

Total annual production |

Marine fisheries |

6.7 mil million tonnes |

|

Inland fisheries |

3.0 mil million tonnes |

|

|

Aquaculture |

2.2 mil million tonnes |

|

|

Sources |

https://www.comhafat.org/fr/files/actualites/doc_actualite_42711114.pdf |

|

|

Contribution to GDP |

Marine fisheries and aquaculture |

$24 billion to the African economy, representing 1.3% of the total African GDP in 2011. |

|

Sources |

https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/africa-program-for-fisheries |

|

|

Employment

|

Marine fisheries |

5,021,000 |

|

Aquaculture |

386,000 |

|

|

Sources |

||

|

Per capita food fish consumption |

9.9 (kg/year) |

|

|

Sources |

Coastal communities in the region are heavily dependent on fisheries (Figures 2.1 and 2.2) for subsistence and local economies[2] from local, SSF operations that supply approximately 60 per cent of marine fish catches. The national economies of many of these countries, however, also rely on industrial, LSF that operate in their waters through foreign fishing agreements.[3] These LSF account for between 10 and 15 per cent of total West African catches, with inland capture fisheries and aquaculture making up roughly 20 per cent of the total fish production.[4] West Africa’s productive and often poorly managed waters are also a hot spot for IUU fishing activity. Such activity results in significant losses in legal revenues for the region estimated at around $1.3 billion USD annually.[5]

Figure 2.1: Map of Sub-Saharan Africa showing Commonwealth countries

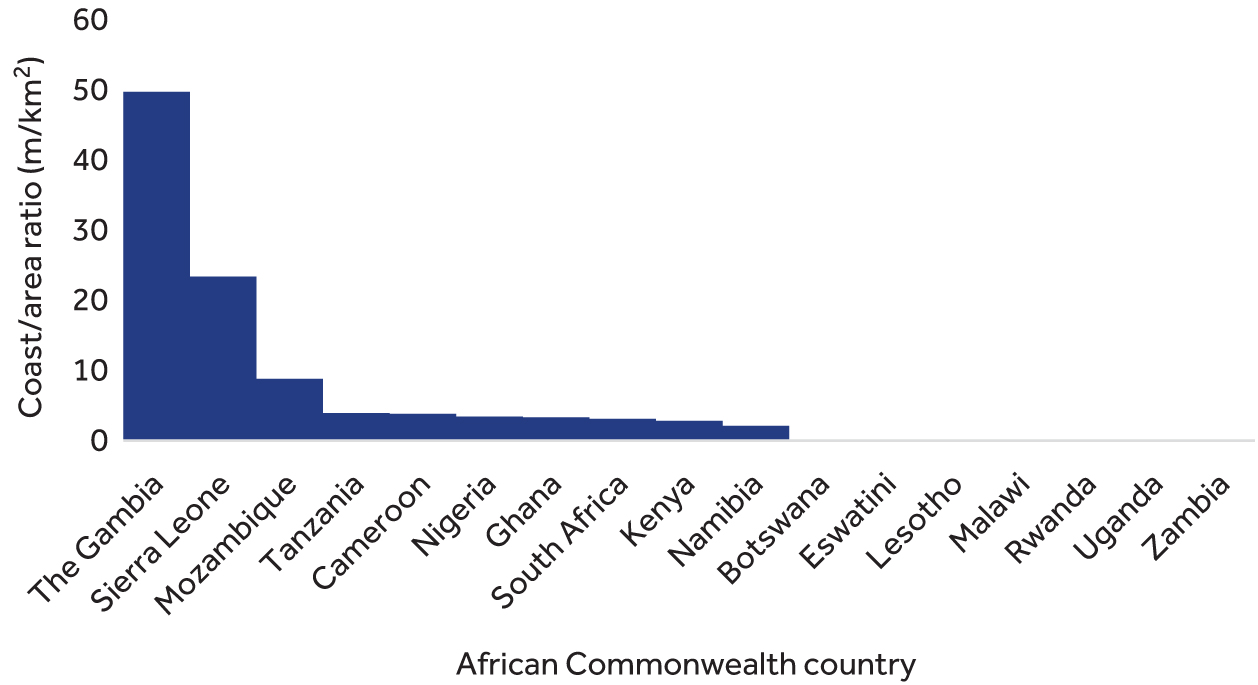

Figure 2.2: Coastline to land area ratio for African Commonwealth countries.

In some instances, this ratio can be used as a useful indicator for a country’s reliance on fisheries resources. Seychelles (1,640 m/km2) and Mauritius (244 m/km2) removed for ease of visualisation.

Fisheries in the Eastern African Commonwealth (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi, Rwanda, Seychelles, Swaziland (Kingdom of Eswatini), Mozambique, Mauritius and Zambia) are similarly vital to local economies in the region.[6] East Africa generally boasts high volumes of the underdeveloped SSF that employ most fishers and fish workers in the region. Fisheries in the region are heavily relied upon for subsistence, as well as local and national economies.[7] For example, fish supplies up to 70 per cent of annual protein consumed in Tanzania. When such figures are compared with estimates that 32.4 per cent of the Eastern African population were affected by undernourishment in 2017, the importance of fisheries to the region is clearly reiterated.[8]

The Southern Cape region of Africa (Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Lesotho) largely mirrors the general fisheries characteristics elsewhere on the continent. Again, marine and inland fisheries make significant contributions to nutrition, food security, livelihoods and employment. The fisheries sector in the region employs approximately 145,000 people, with more than a million benefitting indirectly, and fisheries overall contribute around 2 per cent to Southern Africa’s GDP. Total average exports from the fisheries sector in the Southern Cape region are worth approximately $152 million USD per year, while average imports amount to $100 million USD.[9]

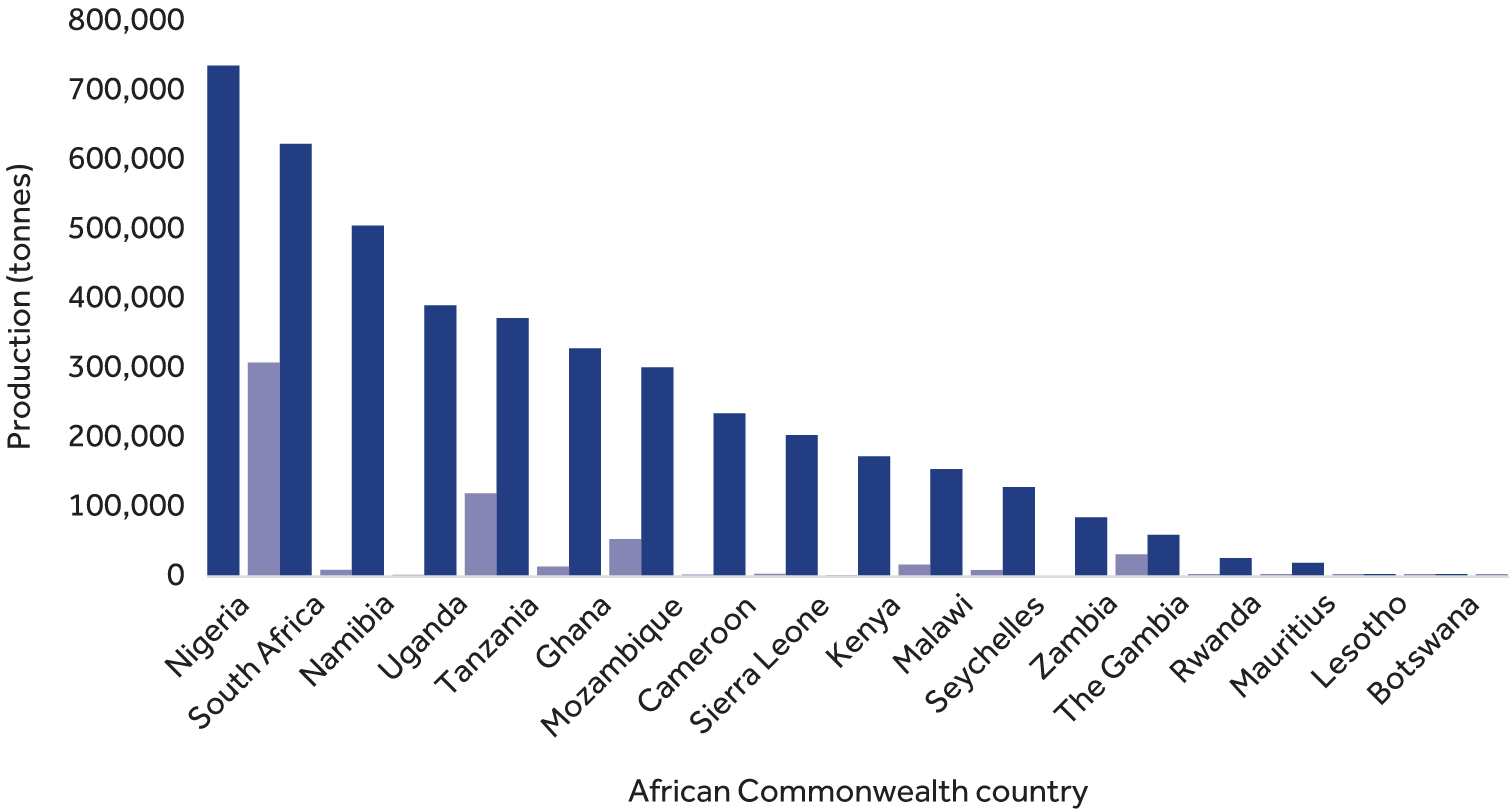

In 2016, South Africa alone produced around 612,200 tonnes of fish, of which 900 tonnes were caught in inland waters, highlighting the importance of small-scale freshwater fishing operations to the region[10] (Figure 2..3). South Africa has a relatively low per capita fish consumption and is traditionally a net exporter of fish products.[11] Meanwhile, Botswana is a landlocked country where fisheries are mainly restricted to the wetlands in the north. Eighty per cent of the national fish catch comes from the Okavango delta, which produced 38 tonnes of catch in 2016 alone. Like South Africa, Botswana has a low per capita fish consumption, estimated at 3.7 kg in 2016.[12] However, unlike South Africa that benefits economically from between 500,000 and 900,000 sports (recreational) fishers and non-consumptive uses of living marine resources such as whale watching,[13] the country plays a host to small volumes of recreational freshwater fisheries due to the seasonal nature of the streams feeding the country’s reservoirs and the lack of diversity of fish species present.[14]

Figure 2.3: Capture fisheries and aquaculture production for the African Commonwealth countries.

Blue bars = fisheries, orange bars = aquaculture. Source: World Bank (2018-2019). No data available for Eswatini.

2.2 Digitalisation in African fisheries

While Africa’s fisheries industry presents many opportunities for digitalisation, it is largely structured around informal business arrangements and as such has considerably untapped potential.

Challenges associated with digitalisation within the fisheries sector in Africa include logistical inefficiencies, lack of proper product storage, illiteracy and a lack of technological skills related to fisheries enterprise. As a result, the leverage of digitalisation into Africa’s fisheries sector is currently low.

2.3 Pillar 1 – Digital innovations in African fisheries

2.3.1 Digital technologies

The core technologies being used within the fishing industry are mostly web-based and are basic overall. In theory, these technologies are readily available online, but illiteracy excludes many from using the web platforms that do exist. There have, however, been some uses of more advanced technology within Africa’s fisheries sector. For example, 2018 saw Moroccan technology start up “ATLAN Space” developed an artificial intelligence (AI) device which when installed on drones enables them to determine the activities being conducted by a vessel in territorial waters.[15] The devices are primed with information regarding marine protected areas, illegal fishing hot spots and the weather, as well as information which enables them to distinguish the behaviour of vessels to determine their activity.[16] Once the tool determines there is a 99 per cent chance that a vessel is fishing illegally, the device activates a response from the drone, which either alerts local authorities or signals to the vessel to stop its current activity.[17]

The benefits of this technology are its ability to bypass the need for human intervention over long distances as the drones can cover a large area and make autonomous decisions.[18] This, in turn, results in a substantial decrease in surveillance costs whilst improving surveillance coverage. ATLAN Space was awarded $150,000 USD to implement drone surveillance to combat IUU fisheries in the Republic of Seychelles through National Geographic’s “Marine Protection Prize”, which aims to attract solutions offering low-cost and easy to maintain technologies relevant to local stakeholders.[19] In November 2020, the company announced that it had raised $1.1 million USD in funding to scale its operations with the aid from Marox Numeric Fund II, Hilmi Law Firm and the Cadex Group.[20]

IUU fisheries within Africa are also being better understood using Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). AIS satellite data is similar to a Global Positioning System (GPS) and is used by large ships to broadcast their position to avoid collisions.[21] The organisation, Global Fishing Watch, collates this AIS data to track the fishing footprint of individual vessels, which is then used to describe and characterise the spatial characteristics of domestic and foreign industrial fishing activities within many different regions globally, including the African EEZ.[22] Poor maritime surveillance and data regarding fisheries activities within African waters means many coastal, African countries regularly suffer from IUU activities, particularly in West Africa.[23] Efforts to utilise AIS data to improve understanding of fisheries activities can therefore have sector-wide benefits. Similarly, vessel monitoring systems (VMS) are a bespoke fisheries management system regulated at the national and regional levels[24] that offer a satellite-based solution for vessel tracking in near real time. Despite VMS posing cost advantages in comparison to at-sea patrols, the initial set up costs of constructing and operating a fisheries monitoring centre are often considered too high for many developing countries.[25]

Global Fishing Watch and Volcan Inc. – combined efforts against IUU fisheries

2020 saw the announcement of a collaboration between non-profit organisation Global Fishing Watch and Vulcan Inc., the creator of maritime information tool Skylight. The partnership aims to provide no-cost access to vessel tracking data and analysis tools to government and agencies through GFW’s platform and Vulcan’s Skylight.[26] In addition, participating governments and agencies have access to GFW analysts, who can provide training and assistance in using the two platforms to monitor, detect and investigate detected suspicious fishing activities. These collaborative efforts aim to aid countries and participating agencies address IUU fisheries through access to near real-time and historical analysis of fishing activities.[27]

2.3.2 Digital solutions and services

The digital solution that has been most widely adopted by the fisheries sector in Africa is digital payment systems. Despite this, the World Bank reports that, although agriculture employs over half the sub-Saharan African population, most farmers (“farmers” refers to those working in agriculture, including fishers and aquaculturists) do not have access to formal financial services. Less than one in six farmers in Africa report receiving payments via a formal bank account. Among those who report savings and borrowing, only one in four save at a formal financial institution and one in five borrows from a formal financial institution.

The digitisation of payments brings with it a number of benefits including timely and safe payments and increased savings and can ultimately contribute to increasing agricultural productivity.[28],[29] For fishing communities and enterprises, the digitisation of payments and savings creates vital links to formal financial institutions and thus expands opportunities to access formal financial services. The lack of financing is one of the main reasons most fishing activities in Uganda, for example, remain artisanal,[30] and this is likely the case across much of the African Commonwealth. The digitisation of payments, however, does face numerous challenges including limited connectivity, poor digital literacy, a weak regulatory environment for digital payments and the limited availability of “cash in cash out” points.[31]

To successfully integrate and utilise such financial services requires the right supporting infrastructure and technology, such as mobile phones and Internet connectivity. In developing countries, mobile phones allow markets to function efficiently as they enable the prices of goods and services to be readily accessed. Markets in rural Africa, however, are often hindered by the inability for information on the prices of goods and services to be widely accessed, especially in the case of SSF.[32]

Mobile phone ownership in Africa is highest in South Africa, where around nine in ten adults own a device, and lowest in Tanzania where three-quarters of adults own a mobile phone.[33] South Africa is the only country in Africa where most mobile phone owners have a smartphone with Internet access (52 per cent of adults). Meanwhile, in Ghana, Senegal, Nigeria and Kenya, only one-third of adults own smartphones, while in Tanzania, this figure is as low as 13 per cent.[34] Furthermore, connectivity within the region is improving, with 4G and 3G connections overtaking 2G in Sub-Saharan for the first time.[35]

A 2011 study on the effects of mobile phone use on the small-scale fishing industry in the Effutu Municipality of Ghana found mobile phone use to have several benefits.[36] Firstly, fishers were able to reduce transaction costs and save time through being able to directly contact suppliers to arrange purchases. Previously, they would have had to travel to suppliers without knowing if what they required was available and would have been unable to “shop the market” easily for the best price. Mobile phone use also allowed fishers to contact customers directly, and over 20 per cent of fishers were able to access new customers using mobile phones. This allowed fishers to cut out the middlemen and sell directly to customers instead of the traditional form of selling through face-to-face auctions at their home landing sites.[37]

Furthermore, mobile phones allow fishers to access pricing information before they land their catch and thus attain the best market price. Forty-eight per cent of fishers agreed that mobile phones lead to reduced price differentials between markets and landing sites. The ability to sell catch prior to landing reduces wastage as most fish caught can be sold prior to landing.[38] This also prevents fishers having to travel around trying to find the best price for their catch and thus also reduces their fuel consumption. Mobile phones also allow fishers to communicate with other fishers to alert them to shoals of fish, which further reduces fuel consumption.[39] The ability of fishers to call for help during emergencies on the water and check weather patterns to avoid poor weather conditions also adds an important safety component to the use of mobile phones in fisheries.[40] A 2009 study conducted on mobile phone utilisation among fishmongers in Western Nigeria found similar results, reporting that fishmonger’s enterprises benefitted from being able to directly contact suppliers and customers alongside monitoring prices,[41] thus highlighting the sector-wide benefits that mobile phone utilisation can produce.

Stakeholders with access to mobile phones are able to access applications that have been specifically designed for the fisheries sector, such as “e-CAS”. “e-CAS” (stands for “Electronic Catch Assessment Survey”) is an Android mobile phone application for digital data capture and analysis.[42] e-CAS was developed in response to calls for a timely, affordable and effective solution to collect catch and fisheries data to address declining fish stocks in Africa’s Great Lakes. Prior to the development of e-CAS, data collection from the Great Lakes was a costly, time-consuming process, often warped by data errors.[43] e-CAS addresses these issues as it allows for data to be collected and sent to a cloud-based database in real time, which means stakeholders have instant access to fisheries and catch data for analysis and reporting. The app has reduced the price for monitoring the Great Lakes fisheries by 70 per cent, while allowing fisheries managers to plan amendments to policies or guidelines using the most up-to-date information possible.[44] Although promising, e-CAS and other mobile-based applications rely on end-users being literate, or trained in utilising apps, and having access to mobile phones and related infrastructure, such as Internet access. Without these prerequisites, the fisheries sector will be unable to benefit from many potential advances in digitalisation (see discussion of the ‘base’, the enabling environment).

2.4 Pillar 2 – Data Infrastructure in African fisheries

Data infrastructure refers to a set of fundamental facilities, the basic structure of a system that is needed to enable multiple sources of data to be sourced, combined, processed, analysed, protected and made accessible for exchange and use. Routine data collection on fisheries catches is limited in many African countries and even less for the socio-economic aspects of fisheries. This hinders the formulation of sound stock management practices and regulatory policies that take into account livelihoods as well as local economics and well-being of fisheries stakeholders.[45] The collection of fisheries data is a costly exercise, which is predominantly reliant on national administrations that allocate finances and sufficient human resources to the task. The lack of such resources and in some cases inefficient data collection schemes often result in African countries relying on poor quality information upon which to manage their fisheries activities. This in turn limits the effectiveness of fisheries management and risk the long-term sustainability of fish populations.[46] This is particularly so when considering the common story of declining resources from both local and foreign fisheries overexploitation and growing populations relying on fish as a protein source. Of the annual catch data submitted by African countries to the FAO in 2011, only 70.4 per cent was considered “satisfactory”, 48.1 per cent was considered to need improvement, 16.7 per cent was “insufficient” and 27.8 per cent of countries did not submit catch data at all.[47]

The limited availability of the quality data and associated data infrastructure[48] is a major factor limiting digitalisation within the fisheries sector. The lack of fisheries data infrastructure across much of the African Commonwealth, such as national and regional databases of fishing vessels with their location and history of IUU operations, is also considered a hindrance to efforts to tackle IUU fisheries.[49] This has prompted endeavours to try and improve the region’s lacking fisheries data, such as “FISH-i Africa”. Fish-i Africa, established in 2012, is a collaborative effort among Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, Somalia and Tanzania, which aim to tackle IUU fisheries.[50] FISH-i Africa uses an innovative and easy-to-use web-based interactive communication platform which allows the transfer and communication of information related to IUU fisheries activities between participants. The online platform allows for the sharing of information and documents, accessing satellite tracking expertise, sharing vessel data, requesting data and discussing IUU incidents to be conducted in real time in a systematic and straightforward manner.[51] FISH-i Africa does not fund or deploy fisheries monitoring systems, but it does promote and encourage the use of AIS and VMS systems to track and identify vessels to record illegal activity. The programme has previously used information shared by monitoring programmes to deny port access to known IUU vessels, has uncovered vessels lacking licenses or using fake licenses, and located vessels evading enforcement officials.[52]

In Ghana, where data collection and management are undertaken by the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, fisheries data that is collected is often inconsistent and only available in print and has not been digitised. The lack of digitally available, quality fisheries data is, however, not specific to Ghana. In Malawi, the Bunda College of Agriculture Library has been working with Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (based in the United Kingdom) since 2008 to visit agriculture sector institutions and libraries to collect, scan and archive printed research information, before ultimately making it available online.[53] In the first 2 years of the project, 484 full-text publications were added to the Global Agriculture Research Archive, of which 85 were on aquaculture and fisheries. The process is also credited with improving cooperation between fisheries and aquaculture institutes.[54] To support efforts to collect and utilise robust fisheries data within the African Commonwealth region, efforts must first be made to ensure there is the necessary data infrastructure to store, analyse and share information collected.

ABALOBI case study – a South African–based, Global Social Enterprise

ABALOBI, a South African–based social enterprise, aims to contribute towards thriving, equitable and sustainable SSF.[55] The ABALOBI FISHER App provides fishers with a digital logbook, which can be downloaded on a simple smartphone, to record catches, post-harvest activities, expenses and income. It also gives fishers access to basic analytics that offer a summary of their monthly activities. Fishers are invited to meet with ABALOBI to collectively review and analyse their data, which in turn stimulates community entrepreneurship and co-management.[56] ABALOBI also facilitate the achievement of equitable, transparent and traceable value chains through the ABALOBI MARKETPLACE app, which allows fishers to sell their products directly to consumers, which shortens the supply chain and improves profits. Consumers are able to track the entire supply chain by scanning a QR code.[57] ABALOBI offer their solutions as a “Software As A Service” (SaaS) package, which is underpinned by Community Development, a Community-Supported Fishery Model, Community-level Fisheries Improvement and Impact Measurement.[58]

Pillar 1 – Digital innovation: ABALOBI’s apps aid fishers in multiple ways. Firstly, the marketplace app enables fishers to set prices for their catch, so that they have more bargaining power. Meanwhile, their fisher app offers an alternative to “blue books” (how catch data was recorded prior to the introduction of ABALOBI, which required fishers to record catch data by hand[59]). Adoption of ABALOBI is high among fishers due to its high value proposition. ABALOBI is not only an electronic logbook but also provides fishers with an accounting tool which enables them to better manage and utilise their income. Once fishers have been through basic business literacy training and created a business plan, the app becomes a very important tool among the fishing communities that ABALOBI work with. Once fishers are onboarded, usage is very high, but getting fishers onboarded in the first place takes time as it requires training. Once onboarded, fishers move from being completely invisible in the market and only being able to sell small volumes of fish to being able to sell a whole basket directly to retailers, restaurants and home users.

Pillar 2 – Data infrastructure: Prior to the introduction of ABALOBI when fishers were working with “blue books”, data was collected once a month, with little feedback given to fishers themselves. Using ABALOBI allows fishers to fill in catch data within a couple of clicks. This process also means that the data that fisheries managers collect is accurate, up-to-date and reflective of all fishers in the sea.[60] ABALOBI data elements and database structures followed the GDST1, GSSI and other ISO standards.

Pillar 3 – Business development: The data captured by ABALOBI can aid fishers in accessing formal financial services, such as loans for repairs. It can also aid in terms of paying tax as they (often for the first time) have detailed data on their income and expenses.[61] In terms of developing ABALOBI, ABALOBI received no support from the South African fisheries authorities, but did receive some money from the government through prize money and grants from technological innovation-focused programmes. Overall, there is very little focus on fisheries as most focus is on financial services and agriculture.

The base – Enabling environment: In terms of users, ABALOBI is their own bottleneck, as they create and deploy their own technology as a SaaS package. ABALOBI’s team actively onboard fishers and offer support and training as well as capacity building. ABALOBI believes that before digitalisation can happen, it is essential to address the social construct behind the sector through engaging with fishers and associated stakeholders to ensure everyone is on the same page. This then enables digitalisation through identifying components that will benefit from digitisation. Mobile phone penetration in South Africa is good, and the challenge with ABALOBI is digital illiteracy. Although many fishers have smartphones and utilise apps such as WhatsApp, their digital literacy does not stretch much further. This makes the training/onboarding offered by ABALOBI fundamental in the uptake of the app. ABALOBI also faces issues as data costs in South Africa are very high. To combat this, ABALOBI’s apps are very basic and require minimal amounts of data for downloading and uploading. Currently, ABALOBI is trying to work with mobile network operators to establish their apps as “zero rating” apps, which would see fishers not charged for the data they use when using the app. In addition, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is keen to help ABALOBI continue to grow and develop potential social/livelihood data collection and monitoring processes.

2.5 Pillar 3 – Business development services in African fisheries

The numerous challenges, including overfishing, over capacity, inadequate human and financial resources, poor market infrastructure and access, and weak governance and regulation, faced by fisheries in Africa limits the capability of local governments to help ensure the sector is sustainable and profitable.[62] In combination with a common lack of government funding destined for the fisheries sector, digitalisation efforts within the sector are often developed by private companies or NGOs. For example, e-CAS was funded privately by a $110,000 USD grant received from the African Great Lakes Conservation fund, administered by The Nature Conservancy (TNC), along with a $500,000 donation from the John D. and Katherine T. MacArthur Foundation.[63] In Ghana, Vodafone was responsible for the launch of an investment-linked insurance product delivered by microinsurance specialists BIMA through the Vodafone mobile money platform to help fishers save and protect against the financial risks associated with death or permanent disability. As Ghana lacks access to traditional bank branches in rural areas, mobile money providers and telecoms companies have played a pivotal role in the accessibility of financial services.[64]

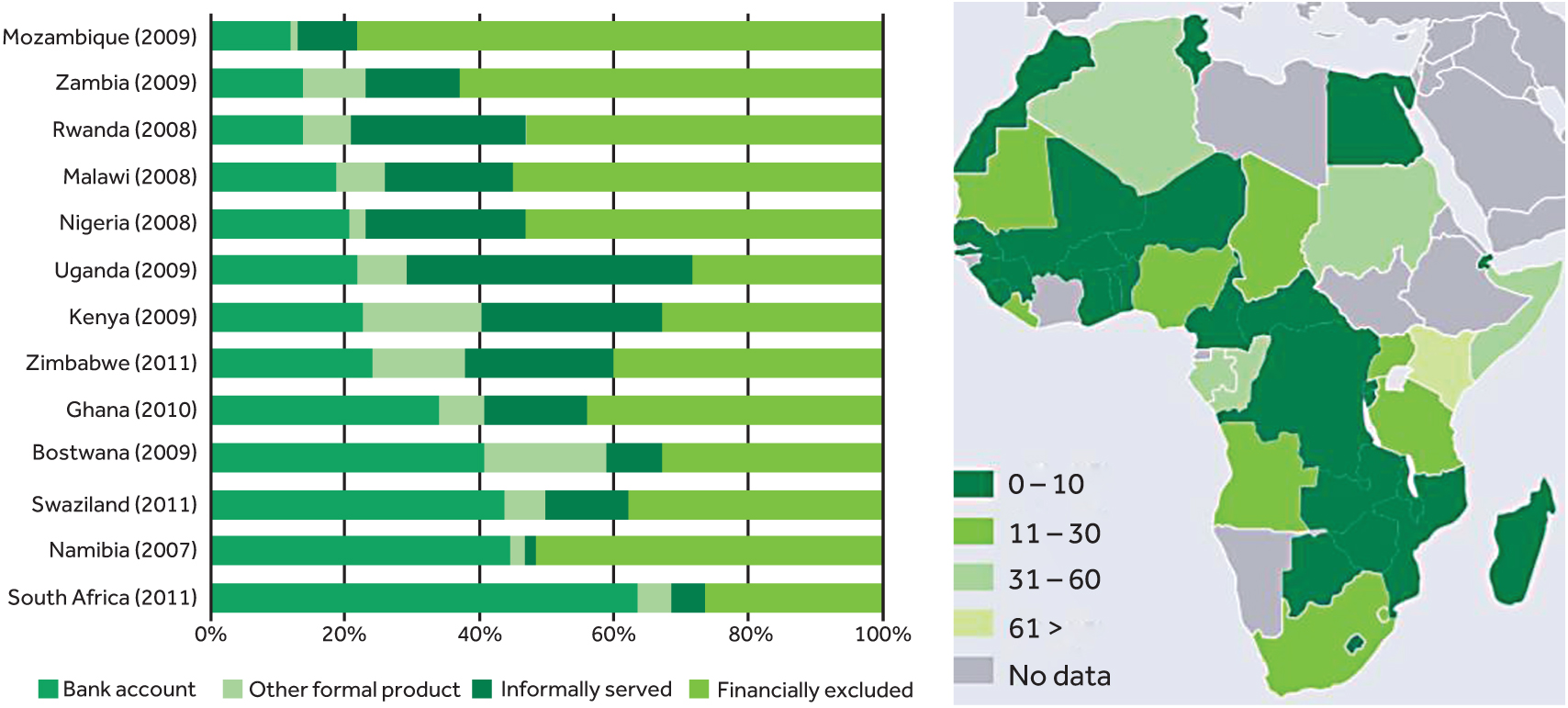

Opportunities for economic diversification are especially limited in Africa’s small island states due to their distance from markets and the limited number of economies of a similar scale. Furthermore, the small island states of Africa face challenges in accessing finance in the forms of grants and loans from institutions such as the World Bank and bilateral donors.[65] Such financing is determined by GDP per capita, and as a result, of often small population sizes, one high net worth individual can skew the overall GDP of states with small populations, thus excluding them from accessing funding. Recent data on financial inclusion versus exclusion is difficult to find; however, an African Development Bank study in 2013[66] shows that financial exclusion is common and is negatively correlated with access to a bank account (i.e., access to a bank account = more financially included) (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4: FinScope access strands in Africa.

Source: Financial Inclusion in Africa. Note: Mozambique, Rwanda and Zimbabwe are not Commonwealth countries. Map showing mobile money users in Africa – i.e., those adults who used a mobile phone to pay bills, send or receive money in the past 12 months (in %). Source: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/Financial_Inclusion_in_Africa.pdf [accessed 28/09/2021]

Access to banks and “financial inclusion” brings more benefits on top of access to credit and formal financial services such as savings and risk mitigation products. Financial inclusion is widely regarded as being a mechanism to improve health and well-being, and a positive relationship between universal access to financial services and improved health has been demonstrated.[67]

There have, however, been efforts made to instigate entrepreneurship within Africa’s fisheries sector. Kenya prioritises agri-business opportunities and youth employment in agriculture, but there is little evidence that this has resulted in successful business models that benefit those in the 18–35 age group.[68] As a result, in 2019, the International Development Research Centre of Canada reported the result of their project which aimed to build the capacity of the country’s youth to develop innovative business models to increase their participation in the fisheries and poultry sectors. A nationwide call for program participants attracted 301 applicants, from which 39 were selected to attend an intensive business training course which included instruction in business plan development, product marketing, financial management, resource mobilisation, information and communication technologies, record keeping, and production and operation management.[69] Each “trainee” then pitched a business plan to a team of industry experts, with the top 20 being selected to receive business counselling and mentoring support to launch their business. The project achieved a 90 per cent business launch success rate for the young entrepreneurs who participated, 60 per cent of whom were women. As Africa’s youth are three times more likely to be unemployed than adults, projects such as this enables young people to access sustainable employment opportunities.[70]

To ensure the success of digitalisation initiatives, there must be investment in training and community engagement. In the case of illiteracy, this requires investment in training and community engagement to ensure new technology and digitalisation are effectively implemented. Training and community engagement projects have been previously implemented within Africa’s fisheries sector. For example, Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit along with their implementing partners (Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation, Directorate of Fisheries Resources, Processing, and export associations (EAIFFPA, UFPEA, AFALU, FFOU), and non-governmental organisations (KATOSI WDT)) offer a suite of “activities” to Uganda, with some also being offered in Kenya and Tanzania. The project, which is set to run from October 2016 to March 2023, has a budget of €10.95 million EUR and aims to aid workers whose livelihood depends on Lake Victoria’s Nile perch fishery. Among their offerings are business development services, such as training programmes and advisory services, to teach basic business skills to small and medium enterprises, especially those involving women.[71]

2.6 The base – Enabling environments for digitalisation in African fisheries

The enabling environment within Africa is not considered “conducive” for the smooth digitalisation of fisheries. In general, there does not appear to be sufficient government prioritisation in the sector. Although fisheries growth and efforts to address IUU fisheries are common in the fisheries sector in Africa, particularly in Western Africa, government spending is not specifically directed at digitalisation but rather focused on increasing production and thus jobs, although digitalisation itself is a tool to support production and jobs.

Although there appears to be a lack of specific focus on government-backed fisheries digitalisation funds, regulatory hurdles for mobile phone and data connectivity companies have eased in recent years, making it easier for companies to increase nation-wide connectivity programmes. Although this has been beneficial for increasing network coverage in many less-developed regions (and thus increased the potential for digitalisation), it is important that such concessions/removal of barriers is not only directed at single companies. This is because the formation of monopolies could risk long-term uptake if monopolisation leads to single-player price hikes that exclude users of the services and thus digital technologies. In addition, if few companies purchase the connectivity goods/services, there is also a risk of monopsony development that could ultimately lead to the same issues as with the formation of monopolies, this time not focused on the connectivity, but on the technologies that utilise the connectivity.

Many of Africa’s governing rules and regulations are considered out of date, having been developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The slow turn around in new governing rules and frameworks will likely hold some African nations back regarding digitalisation development.

- The 2016 EU Global Data Protection regulation[72] has been slow to percolate on the African continent even though it is considered a standard model for many. Africa serves as a test ground for many technologies despite many inhabitants still being largely excluded from enjoying basic rights regarding their personal information. As of March 2020, only 24 out of 53 African countries have adopted laws and regulations to protect personal data.[73]

- Many of Africa’s current technology laws and regulations make little to no mention of new and upcoming technologies such as blockchain and distributed ledger technologies, the Internet of things (IoTs), AI and machine learning.

Many fisheries workers suffer from unstable income streams and an inability to look more than days to weeks ahead when it comes to financial planning. This largely excludes them from finance models that either require large down payments or those that are subscription based. For this reason, pay as you go finance models are hugely beneficial in promoting the uptake of new digitalisation technologies that require mobile connectivity. This is particularly so when initial uptake is plagued with scepticism about the technology being promoted. Low start-up fees based on pay as you go models often allow users to try new technologies without being tied into long-term engagements.

It is widely accepted that much of Africa’s education and training programmes suffer from low-quality teaching and learning.[74] Although not directly correlated to digitalisation development and success, education overall does have a bearing on the uptake of certain digital technologies that require literacy skills. Considering Africa will account for 57 per cent (1.4 billion people) of global population growth by 2055, and Sub-Saharan African has the largest growing youth (<18 years old) population in the world,[75] improving the educational status across the African Commonwealth will have significant impacts on the state of technology adoption and ultimately fisheries digitalisation in the region. With 52 per cent of Africa’s total workforce expected to have a secondary education (or higher) by 2030, the opportunities for sustainable fisheries development using digital technologies are clear. It is also interesting to note that with increased education and potentially more opportunities for non-labour-related careers, fisheries sectors in certain countries may experience reductions in workforce although this remains speculative until more research is carried out and/or such effects can be evaluated in the future. Note: The Commonwealth’s new Global Youth Development Index Report[76] will be an important addition to the state-of-the-art knowledge on education and employment (among other things) for Africa’s youth populations.

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆

[1] West Africa | Coastal Fisheries Initiative | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/in-action/coastal-fisheries-initiative/activities/west-africa/en/

[2] West Africa | Coastal Fisheries Initiative | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/in-action/coastal-fisheries-initiative/activities/west-africa/en/

[3] European Union (2020) ‘Sustainable fisheries partnership agreements (SFPAs)’. https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/fisheries/international-agreements/sustainable-fisheries-partnership-agreements-sfpas_en

[4] Katikiro, R. and E. Macusi (2012) ‘Climate Change on West African Fisheries and its Implications on Food Production’. Journal of Environmental Science and Management 15, 83–95.

[5] World Bank. ‘Africa Program for Fisheries’. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/africa-program-for-fisheries

[6] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[7] The Commonwealth. ‘Fisheries and the Fishing Industry in Commonwealth Countries’. Commonwealth of Nations.

[8] Interannual Monsoon Wind Variability as a Key Driver of East African Small Pelagic Fisheries | Scientific Reports (2020). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-70275-9

[9] South African Development Fund. ‘Southern African Development Community: Fisheries’. https://www.sadc.int/themes/natural-resources/fisheries/

[10] FAO. ‘FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Republic of South Africa’. http://www.fao.org/fishery/facp/ZAF/en

[11] FAO. ‘FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Republic of South Africa’. http://www.fao.org/fishery/facp/ZAF/en

[12] FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Republic of Botswana. Fisheries and Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles - Botswana (fao.org)

[13] FAO. ‘FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Republic of South Africa’. http://www.fao.org/fishery/facp/ZAF/en

[14] FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture – Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles – The Republic of Botswana. Fisheries and Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles - Botswana (fao.org)

[15] Atlan Space | AISDG. https://www.aiforsdgs.org/all-projects/atlan-space

[16] UNEP (2018). Intelligent Drones Crack Down on Illegal Fishing in African Waters. http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/intelligent-drones-crack-down-illegal-fishing-african-waters

[17] Atlan Space | AISDG. ttps://www.aiforsdgs.org/all-projects/atlan-space

[18] UNEP (2018). Intelligent Drones Crack Down on Illegal Fishing in African Waters. http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/intelligent-drones-crack-down-illegal-fishing-african-waters

[19] National Geographic Awards Innovators Combating Illegal Fishing (2018) The Maritime Executive. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/national-geographic-awards-innovators-combating-illegal-fishing

[20] Moroccan startup Atlan Space raises $1.1 million in Series A round (2020) Innovation Village | Technology, Product Reviews, Business. https://innovation-village.com/moroccan-startup-atlan-space-raises-1-1-million-in-series-a-round/

[21] Downloadable Fishing Effort Data. Global Fishing Watch. https://globalfishingwatch.org/dataset-and-code-fishing-effort/

[22] Li, M.-L. Ota, Y., Underwoord, P.J., Reygondeau, G., Seto, K., Lam., V.W.Y., William, D.K., and Cheung, W. L. (2021) ‘Tracking Industrial Fishing Activities in African Waters from Space’. Fish and Fisheries 22, 851–864.

[23] Fishing in African waters: New Study Utilizes Satellite Data to Track Industrial Fishing Activities in Coastal African Waters (2021) ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/04/210427163246.htm

[24] Global Fishing Watch. Understanding Fishing Activity Using AIS and VMS Data. https://globalfishingwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/Understanding-Fishing-Activity.pdf

[25] The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) (2018) Out of the Shadows: Improving Transparency in Global Fisheries to Stop Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing. https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/Transparency-report-final.pdf

[26] Seafood Source (2020) ‘Global Fishing Watch Forms Collaboration With Vulcan Inc’. https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/environment-sustainability/global-fishing-watch-forms-collaboration-with-vulcan-inc

[27] Bladen, S. (2020) ‘Technology Collaboration Aims to Strengthen Fisheries Monitoring and Control’. Global Fishing Watch. https://globalfishingwatch.org/press-release/technology-collaboration/

[28] The World Bank (2020) Digitization of Agribusiness Payments in Africa Building a Ramp for Farmers Financial Inclusion and Participation in a Digital Economy.

[29] WorldFish (2020) Information and Communication Technologies for Small-Scale Fisheries (ICT4SSF) – A Handbook for Fisheries Stakeholders. FAO. doi: 10.4060/cb2030en.

[30] Market Scoping Study for the Digitization of the Fish Value Chain in Uganda – UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). https://www.uncdf.org/article/5875/market-scoping-study-for-the-digitization-of-the-fish-value-chain-in-uganda

[31] The World Bank (2020) Digitization of Agribusiness Payments in Africa Building a Ramp for Farmers Financial Inclusion and Participation in a Digital Economy.

[32] Salia, M., N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah and W.F. Steel (2011) ‘Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Artisanal Fishing Market Efficiency and Livelihoods in Ghana’. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 47, 1–26.

[33] Basic Mobile Phones More Common than Smartphones in Sub-Saharan Africa (2018) Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/10/09/majorities-in-sub-saharan-africa-own-mobile-phones-but-smartphone-adoption-is-modest/

[34] Basic Mobile Phones More Common than Smartphones in Sub-Saharan Africa (2018) Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/10/09/majorities-in-sub-saharan-africa-own-mobile-phones-but-smartphone-adoption-is-modest/

[35] Mobile Connectivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: 4G and 3G Connections Overtake 2G for the First Time (2020) Mobile for Development. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/blog/mobile-connectivity-in-sub-saharan-africa-4g-and-3g-connections-overtake-2g-for-the-first-time/

[36] Salia, M., N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah and W.F. Steel (2011) ‘Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Artisanal Fishing Market Efficiency and Livelihoods in Ghana’. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 47, 1–26.

[37] Salia, M., N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah and W.F. Steel (2011) ‘Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Artisanal Fishing Market Efficiency and Livelihoods in Ghana’. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 47, 1–26.

[38] Salia, M., N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah and W.F. Steel (2011) ‘Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Artisanal Fishing Market Efficiency and Livelihoods in Ghana’. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 47, 1–26.

[39] Salia, M., N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah and W.F. Steel (2011) ‘Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Artisanal Fishing Market Efficiency and Livelihoods in Ghana’. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 47, 1–26.

[40] Salia, M., N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah and W.F. Steel (2011) ‘Effects of Mobile Phone Use on Artisanal Fishing Market Efficiency and Livelihoods in Ghana’. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 47, 1–26.

[41] Ifejika, P., G. Nwabeze, J. Ayanda and A. Asadu (2009) ‘Utilization of Mobile Phones as a Communication Channel in Fish Marketing Enterprise among Fishmongers in Western Nigeria’s Kainji Lake Basin’. Journal of Information Technology-Impact 9.

[42] Digitized Data Conserves Africa’s Great Lake Fisheries (2021) https://blog.nature.org/science/2021/02/10/digitized-data-conserves-africas-great-lake-fisheries/

[43] Digitized Data Conserves Africa’s Great Lake Fisheries (2021) https://blog.nature.org/science/2021/02/10/digitized-data-conserves-africas-great-lake-fisheries/

[44] Digitized Data Conserves Africa’s Great Lake Fisheries (2021) https://blog.nature.org/science/2021/02/10/digitized-data-conserves-africas-great-lake-fisheries/

[45] Asche, F. Garlock, T.M., Akpalu, W., Amaechina, E.C., Botta, R., Chukwuone, N.A. Hutchings, K., Lokina, R., Tibesigwa, B., Turpie, J., and Eggert, H. (2021) ‘Fisheries Performance in Africa: An Analysis Based on Data from 14 Countries’. Marine Policy 125, 104263.

[46] NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency, African Union InterAfrican, Bureau for Animal Resources, & African Union InterAfrican (2016) The Pan-African Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy Framework and Reform Strategy: Improving of Fisheries and Aquaculture Data Collection and Analysis.

[47] NEPAD Planning and Coordinating Agency, African Union InterAfrican, Bureau for Animal Resources, & African Union InterAfrican (2016) The Pan-African Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy Framework and Reform Strategy: Improving of Fisheries and Aquaculture Data Collection and Analysis.

[48] Lack of Big Data Weakens Efforts to Restrain Illegal Fishing in Africa. Stop Illegal Fishing. https://stopillegalfishing.com/press-links/lack-big-data-weakens-efforts-restrain-illegal-fishing-africa/

[49] Dahir, A.L. ‘A Lack of Big Data Is Hampering Efforts to Curb Illegal Fishing in Africa’. Quartz. https://qz.com/africa/1182628/illegal-fishing-in-africa-aided-by-lack-of-big-data/

[50] Our Task Force | FISH-i. https://fish-i-network.org/about/our-task-force/

[51] FISH-i-Africa (2014) The FISH-i Africa Task Force. https://panorama.solutions/sites/default/files/FISH-i_Task_Force_-_Flyer.pdf

[52] Fujita, R., C. Cusack, R. Karasik, H. Takade-Heumacher and C. Baker (2018) ‘Technologies for Improving Fisheries Monitoring’. 71. https://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/oceans/Technologies_for_Improving_Fisheries_Monitoring.pdf

[53] Salanje, G. F. (2011) ‘Collection of Malawi’s Scientific Grey Literature for Local and International Use’. 6.

[54] Salanje, G. F. (2011) ‘Collection of Malawi’s Scientific Grey Literature for Local and International Use’. 6.

[55] ABALOBI – Elevating Small-Scale Fisheries Through Technology. ABALOBI. http://abalobi.org/about/

[56] In Their Own Words: How ABALOBI, the Environmental Defence Fund, the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation and the Environmental Law Institute Are Helping to Implement the SSF Guidelines | Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2021) http://www.fao.org/voluntary-guidelines-small-scale-fisheries/news-and-events/detail/en/c/1370947/

[57] In Their Own Words: How ABALOBI, the Environmental Defence Fund, the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation and the Environmental Law Institute Are Helping to Implement the SSF Guidelines | Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2021) http://www.fao.org/voluntary-guidelines-small-scale-fisheries/news-and-events/detail/en/c/1370947/

[58] ABALOBI – Elevating Small-Scale Fisheries Through Technology. ABALOBI. http://abalobi.org/about/

[59] ABALOBI: ICTs for Small-Scale Fisheries Governance (2016) https://panorama.solutions/en/solution/abalobi-icts-small-scale-fisheries-governance

[60] ABALOBI: ICTs for Small-Scale Fisheries Governance (2016) https://panorama.solutions/en/solution/abalobi-icts-small-scale-fisheries-governance

[61] ABALOBI: ICTs for Small-Scale Fisheries Governance (2016) https://panorama.solutions/en/solution/abalobi-icts-small-scale-fisheries-governance

[62] Chan, C.Y. Tran, C., Pethiyagoda, S., Crissman, C.C., Sulser, T.B., Phillips, M.J. (2019) ‘Prospects and Challenges of Fish for Food Security in Africa’. Global Food Security 20, 17–25.

[63] Digitized Data Conserves Africa’s Great Lake Fisheries (2021) https://blog.nature.org/science/2021/02/10/digitized-data-conserves-africas-great-lake-fisheries/

[64] Loukos, P. and A. Javed (2018) Opportunities in Agricultural Value Chain Digitalisation: Learnings from Ghana. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Opportunities-in-agricultural-value-chain-digitisation-Learnings-from-Ghana.pdf

[65] Bafana, B. (2021) ‘Africa: Digital Tech Can Help African Island States Cope With Climate Change’. allAfrica.com. https://allafrica.com/stories/202108280002.html

[66] Demirgüç-Kunt, A. Klapper, L. (2013) Financial Inclusion in Africa. 148.

[67] Gyasi, R.M., S. Frimpong, G.K. Amoako and A.M. Adam (2021) ‘Financial Inclusion and Physical Health Functioning Among Aging Adults in the Sub-Saharan African Context: Exploring Social Networks and Gender Roles’. PLoS ONE 16, e0252007.

[68] Expanding Business Opportunities for Youth in the Fish and Poultry Sectors in Kenya | IDRC – International Development Research Centre (2019) https://www.idrc.ca/en/research-in-action/expanding-business-opportunities-youth-fish-and-poultry-sectors-kenya

[69] Expanding Business Opportunities for Youth in the Fish and Poultry Sectors in Kenya | IDRC – International Development Research Centre (2019) https://www.idrc.ca/en/research-in-action/expanding-business-opportunities-youth-fish-and-poultry-sectors-kenya

[70] Expanding Business Opportunities for Youth in the Fish and Poultry Sectors in Kenya | IDRC – International Development Research Centre (2019) https://www.idrc.ca/en/research-in-action/expanding-business-opportunities-youth-fish-and-poultry-sectors-kenya

[71] Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale & Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (2021) Sustainable Fisheries in Uganda. https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2021-en-uganda-sewoh.pdf

[72] General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – Official Legal Text. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/

[73] Privacy International (2020) 2020 is a Crucial Year to Fight Data Protection in Africa. 2020 is a crucial year to fight for data protection in Africa | Privacy International

[74] Africa Grapples With Huge Disparities in Education (2017) Africa Renewal. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2017-march-2018/africa-grapples-huge-disparities-education

[75] Nations, U. Population. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/population

[76] The Commonwealth (2021) Hydrant (http://www.hydrant.co.uk) New Global Youth Development Index Shows Improvement in the State of Young People.https://thecommonwealth.org/media/news/new-global-youth-development-index-shows-improvement-state-young-people

Digital Fisheries report homepage Next chapter Back to top ⬆