By Dr Mohamed Z M Aazim, Adviser, Debt Management, Commonwealth Secretariat.

Sovereign credit ratings help shape how Commonwealth countries engage with global financial markets. Created to independently assess a country's ability and willingness to repay its debt, sovereign credit ratings influence interest costs, investor confidence, and access to long‑term finance, especially for small and emerging economies. For many Commonwealth countries, a rating is more than a label. It signals stability, strengthens policy credibility, and widens options to fund development.

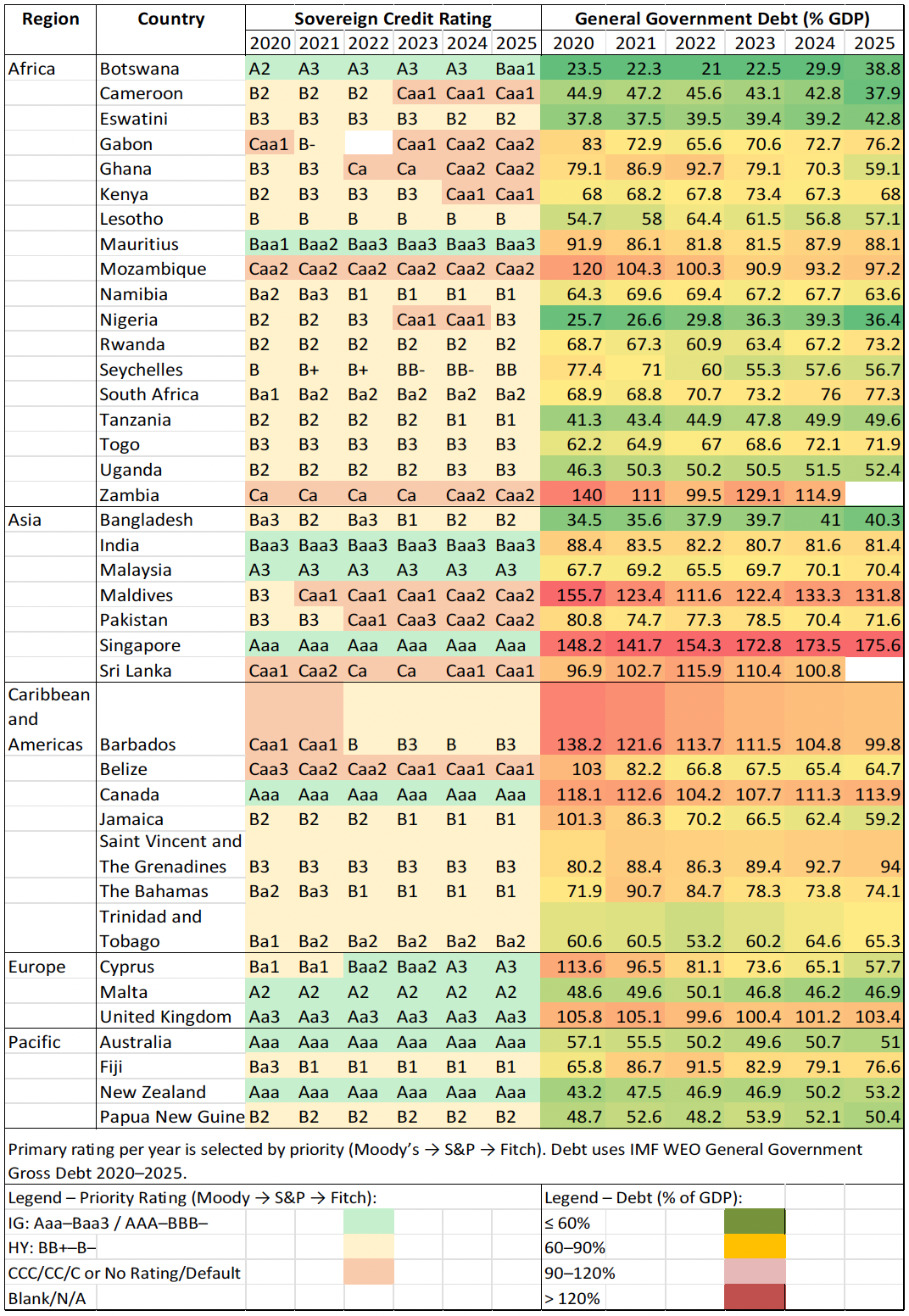

Between 2020 and 2025, ratings coverage across the Commonwealth remained broadly stable. Of 56 Commonwealth countries, 39 held at least one sovereign rating, allowing meaningful comparison across regions. Coverage is widest in Africa (18), followed by Asia (7), the Caribbean & Americas (7), the Pacific (4), and Europe (3, all rated). This distribution largely reflects the composition of the Commonwealth rather than significant changes in rating agency engagement.

Investment‑Grade (IG) top performers

As of 2025, 11 Commonwealth countries (Australia, Botswana, Canada, Cyprus, India, Malaysia, Malta, Mauritius, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United Kingdom) are IG (Aaa–Baa3 / AAA–BBB–). These sovereigns pair strong institutions with credible fiscal and monetary frameworks and deep financial markets, preserving market access and moderating funding costs through global cycles. In other words, IG means the country is trusted to pay back what it borrows and spans all regions, concentrated among advanced and upper‑middle‑income economies where resilient policy frameworks and diversified funding bases help absorb shocks.

Why ratings change over time

Shifts in ratings during 2020-2025 reflect well documented drivers in rating agency reviews. Commodity price and terms of trade swings altered fiscal revenues and external balances, especially where buffers were thin. Tighter global financial conditions raised interest burdens and rollover risks, particularly with short‑dated, foreign‑currency, or non‑resident‑held debt. Post pandemic debt overhangs and weak revenue mobilisation constrained policy space. Financial intermediaries and sovereign linkages and contingent liabilities, including state‑owned enterprises (SOEs), occasionally crystallised into general government debt. The direction of ratings ultimately depended on the coherence of policy coordination and the credibility of reform implementation from domestic revenue measures to public financial management and SOE governance reforms.

Higher debt does not determine ratings

General Government Debt (GGD), which covers borrowing by the central government and SOEs, as a share of GDP is a key measure used to judge a country’s financial risk. Higher debt reduces fiscal space and increases vulnerability to shocks. For below‑IG issuers, it can intensify a ‘cliff effect’ where downgrades sharply restrict market access.

Yet debt alone is not determinative. Several IG members carry relatively high GGD but remain strongly rated thanks to deep domestic markets, credible institutions, robust revenues, diversified funding, and the capacity to borrow in local currency. In essence, the institutional environment determines how much risk a given debt level represents.

After stress, signs of improvement

A number of non‑IG Commonwealth countries are moving forward after acute debt challenges. This can happen when governments pursue externally supported fiscal consolidation, strengthen revenue administration, improve debt transparency, and tighten SOE oversight, to rebuild credibility. Sri Lanka and Ghana exemplify economies working through restructuring legacies toward macro stabilisation, where steady primary balance improvements and realistic medium‑term planning can support progressive rating recovery.

Commonwealth rating picture

With Africa accounting for 18 of the 39 rated Commonwealth countries, Commonwealth wide trends naturally reflect African dynamics from commodity exposure and climate shocks to the benefits of deepening domestic debt markets. Asia and the Caribbean & Americas each contribute seven rated members spanning advanced, emerging, and small state contexts. Europe’s three Commonwealth countries are all investment grade, reflecting long standing institutional strength. In the Pacific, four rated members include two advanced anchors (Australia and New Zealand) and two small island economies where climate vulnerability, remoteness, and market size shape funding strategies and rating outcomes.

Outlook – stability through reform and credibility

The 2020-2025 period underscores resilience across Commonwealth. Where fiscal anchors are credible, reforms are well signalled, and buffers are prudently managed, market access has held up. Where anchors are uncertain, maturities bunch, or foreign exchange exposures are high, conditions tighten. For reform minded Commonwealth countries, the path forward is clear. Credible fiscal consolidation, deeper domestic markets, transparent debt reporting, stronger SOE governance, and active investor relations form a coherent package that supports rating stability and upgrade potential across diverse contexts. The accompanying table and figure reflect this baseline, 39 rated members, 11 at IG, and a regional distribution led by Africa.