The Commonwealth Blue Charter is highlighting case studies from the Commonwealth and beyond, as part of a series to spotlight best practice successes and experiences.

Share your own case study with us

“With over 1.35 million km2 of ocean, the people of Seychelles have a direct dependence on our ocean resources for food security and livelihoods. Developing a Marine Spatial Plan is a way of tackling the sustainable development of the ocean for today and future generations.”

Former President Danny Faure¹

Summary

Seychelles has long been a leader in biodiversity conservation and, in 2012, when less than 1 per cent of its marine waters were managed in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), the president made an ambitious commitment to protect over 30 per cent by 2020. At the same time, the economic situation meant that there were strong incentives to develop the country’s Blue Economy. Lastly, concerns about the impacts of climate change on this small island developing state were growing because of sea level rise and increasing sea surface temperatures. Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) was therefore adopted as the tool to ensure that, in protecting new areas of ocean, biodiversity goals would be balanced with the requirement for a sustainable national economy. New MPAs, formally announced in March 2020, are a key part of the Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan (SMSP) that will be completed in 2021. The SMSP will also address sustainable use of marine resources in the remaining 70 per cent of ocean and climate change adaptation, and will coordinate appropriate regulatory compliance and unified government oversight of all activities. This case study looks at how MSP has been used to develop the recommendations to expand marine biodiversity protection in Seychelles.

The Issue

In 2012, at the Rio +20 Conference, the Government of Seychelles (GOS) committed to protecting 30 per cent of its 1.35 million km2 marine waters in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs),² as a pledge conditional to raising US$2.5 million/year for a conservation and adaptation fund. At that time, although over 47 per cent of the land was protected, only 0.04 per cent of marine waters were in MPAs. Environmental concerns are firmly entrenched in the Constitution of Seychelles, and the country has multiple policies and strategies to promote, coordinate and integrate sustainable development and to expand biodiversity protection. With such a large ocean area and with over two-thirds of Seychelles’ economy reliant on the ocean, there was a need to develop a marine plan for the country’s ocean space.

The Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan (SMSP) Initiative³ was developed as an integrated, multi-sector approach to address the need to support the Blue Economy (i.e. businesses that rely on ocean resources, marine-based food security and marine livelihoods) with climate change adaptation and biodiversity protection. The SMSP provides information to government and stakeholders about what is allowed and where and identifies the new MPAs.

The response

Marine spatial planning (MSP) is an iterative process that takes place over a number of years, using spatial data and stakeholder participation to create an evidencebased plan. Plans are living documents and, after implementation, are monitored, adapted and revised as new information and data become available, new objectives or values emerge that are important to marine users, and ocean uses and activities change. The SMSP process was designed using United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization guidance⁴ as well as other publications and reports, combined with information from discussions with colleagues and experts. This ensured the use of best practices and lessons learnt from other geographies such as Australia,⁵ Canada⁶ and the Eastern Caribbean⁷ to adapt the process to the local context.

Article 38 of the Seychelles Constitution,⁸ along with the Seychelles Sustainable Development Strategy,⁹ requires the implementation of “an integrated marine plan to optimise the sustainable use and effective management of the Seychelles marine environment while ensuring and improving the social, cultural and economic wellbeing of its people” and this provides the background for the marine plan. The SMSP Initiative was launched with three objectives: to expand protection of marine waters to 30 per cent, to address climate change adaptation and to support the Blue Economy.¹⁰

A key part of meeting the objectives for the 30 per cent protection goal and supporting the Blue Economy was designing a zoning framework for the full 1.35 million km2. Development of this was informed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ecological and socio-economic criteria for MPA networks,¹¹ the IUCN guidelines for MPAs on protected area categories,¹² lessons learnt from other countries, tools for biodiversity prioritisation (e.g. Marxan) and consultations with experts. The zoning process was defined in two phases with three Milestones, the first two of which were focused primarily on proposals for deep water and the third on deep and shallow water. This was because most marine activities other than industrial tuna fishing occur in waters less than 200 m deep and it took longer to gather the necessary data and develop those proposals.

Scientific data, local expert knowledge and stakeholder input for maps showing habitats, species and marine uses and activities began in Milestone 1. Information was also obtained from international research expeditions such as National Geographic Pristine Seas in 2015 and the Nekton Expedition in 2019. Two Marxan analyses were undertaken: the first was a project led by GOS United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)Global Environment Facility (GEF) (Klaus, 2015¹³) and led to an initial analysis; and the second was a rapid “Marxan with Zones” project using three scenarios (biodiversity bias, Blue Economy bias, economic bias), which led to suggestions for establishing three different zones across the marine waters: High Protection, Medium Protection and Multiple Use. Customised decision-support tools were developed to check representation goals against 30 per cent area targets.

Over 100 stakeholders are participating and engaged from more than 11 marine sectors, including commercial fishing, tourism and marine charters, biodiversity conservation, renewable energy, port authority, maritime safety and non-renewable resources. To date there have been 210 committee meetings, workshops and public information sessions, an additional 52 workshops for the Outer Islands (GOS-UNDP-GEF Outer Islands Project) and bilateral consultations with marine sectors, local experts and agencies. The results of these activities were used to develop the zoning framework and new MPAs, and further discussions are being held in order to prepare a table of Allowable Activities for the different zone, and to develop other management considerations.

Partnerships and support

The SMSP initiative is a government-led process, and started in 2014. The Nature Conservancy (TNC) leads the process design on behalf of the government, provides all technical and scientific support and undertakes planning, facilitation and project management with support from the GOS-UNDP GEF Programme Coordinating Unit.

The SMSP is a necessary output from the Seychelles debt conversion, which created the Seychelles’ Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT), an independent public-private trust operationalised in 2016. The Trust is responsible for managing debt conversion proceeds including disbursing blue grants and investment assets funded by the debt conversion deal.¹⁴ Under this deal, private philanthropic funding and loan capital were raised, and SeyCCAT then extended loans to GOS to enable the purchase of US$21.6 million of sovereign debt at a discount. GOS now repays SeyCCAT on more favourable terms, allowing SeyCCAT to direct a portion of the repayments for financing of marine conservation and climate change adaptation projects and, in the long term, implementation of the SMSP. Additional funding is being provided through grants to GOS, an Oceans 5 grant awarded to TNC, and some private funders. Approximately US$250,000 is spent on the SMSP per year.

Results, accomplishments and outcomes

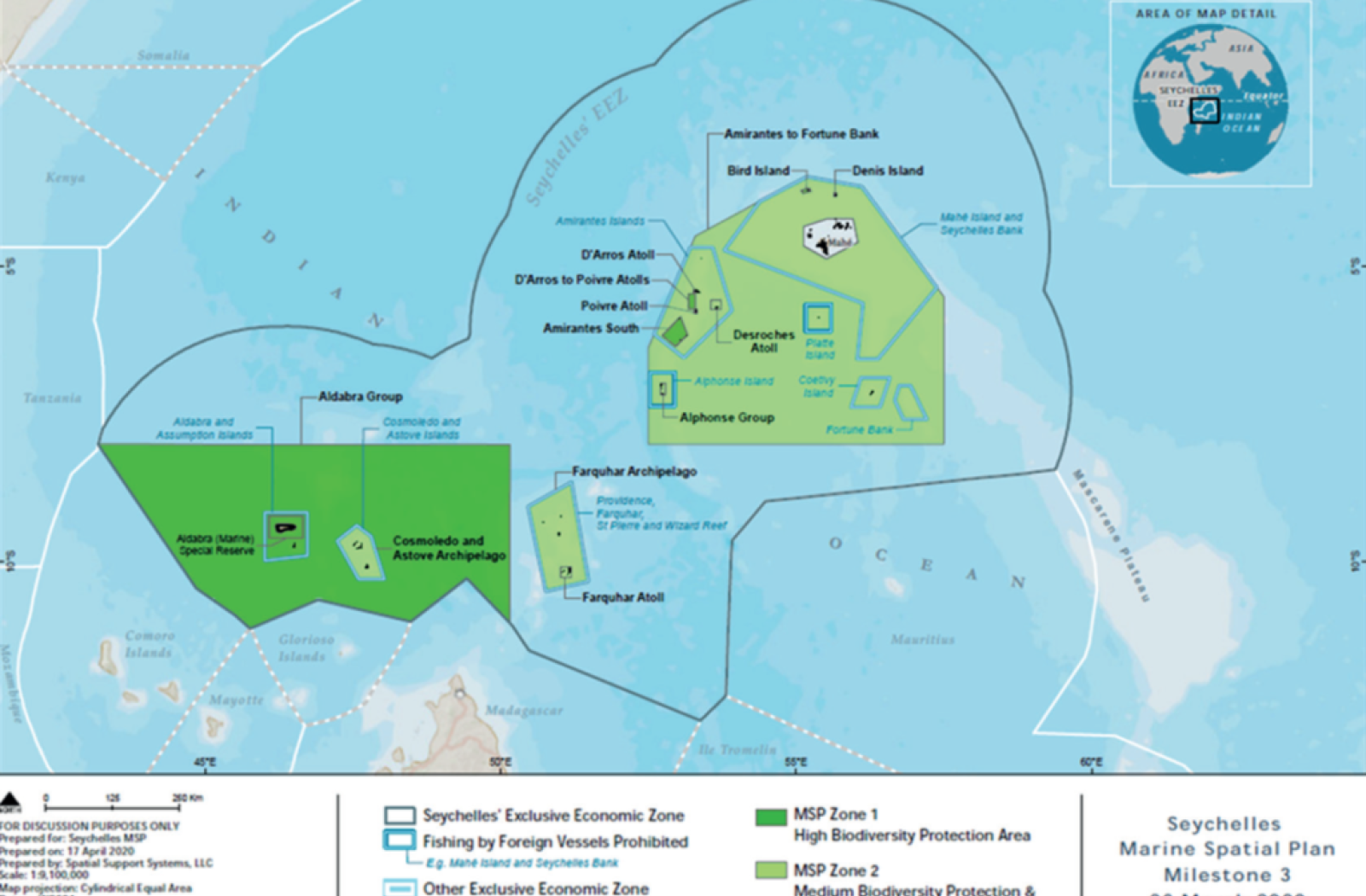

As per the debt conversion commitment, Milestone 1 (2014-2018) resulted in protection of 15 per cent of the marine waters through gazette of the new Zone 1 and 2 areas in February 2018. Milestone 2 (2018-2019) refined the zoning design and expanded Zones 1 and 2 to include a further 11 per cent of marine waters, which were gazetted in April 2019, bringing the total area protected to 26 per cent. This Milestone included an economic analysis undertaken with a fisheries expert and an economist to evaluate the potential impact of the zones on industrial tuna fishing. Milestone 3 (20192020) involved an estimate by an economist of the costs required to implement the new MPAS, and final gazettements during this Milestone achieved the 30 per cent protection goal in March 2020. The total area protected includes MPAs that were designated before the SMSP process was initiated, such as Aldabra Marine Reserve. The MPAs are thus as follows:

-

High Biodiversity Protection Areas:

Known collectively as Zone 1 and covering 203,071 km2 (15 per cent of Seychelles waters), these five areas (Aldabra Group, Bird Island (Île aux Vaches), D’Arros Atoll, D’Arros to Poivre Atolls, Amirantes South) are designated as MPAs under the National Parks and Nature Conservancy Act (NPNCA) and are designed to conserve and protect the top priority areas for marine and coastal biodiversity, including those of international significance. MPAs contain habitats and species that may be rare, endangered, unique or with narrow distribution ranges, as well as breeding or spawning areas, key foraging habitat, fragile or sensitive species and habitats. Each site is large enough to ensure ecological resilience and to provide climate change adaptation. In the draft Allowable Activities table, extractive activities and those that alter the seabed are not allowable.

-

Medium Biodiversity Protection and Sustainable Use Areas:

Known collectively as Zone 2 and covering 238,442 km2, these eight areas (Amirantes to Fortune Bank, Denis Island, Desroches Atoll, Poivre Atoll, Alphonse Group, Farquhar Atoll, Farquhar Archipelago, Cosmoledo and Astove Archipelago) are designed with the objective of biodiversity protection and sustainable use and are designated as Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) under the NPNCA. They include habitats and species that have some tolerance to disturbance and human use and include regionally and nationally significant areas; the draft Allowable Activities include sustainable fishing, tourism and renewable energy. Zone 2 is considered suitable for some level of extraction and sea-bed alteration depending on the specific location, provided there is appropriate consultation and management to achieve the objective of the area.

Zone 3 is Multiple Use and covers the remaining 70 per cent of Seychelles waters. It will be finalised in 2020-2021 at which point the SMSP will be implemented through a phased approach, which is still being developed.

The new MPAs will be implemented through existing or new legislation; regulations will be passed for uses and activities, management plans will be developed and IUCN protected area management categories will be assigned as appropriate. The SMSP website¹⁵ provides information on all the outputs of the initiative including a spatial data catalogue, an Atlas, the MSP Policy, economic assessments and the legal gazettes for the new MPAs.

COVID-19: The greatest current challenge in most countries is recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

All countries and MPAs around the world have seen a massive negative impact. With the cessation of tourism, many sources of income have dried up. MPA managers have had to focus on ensuring the safety and security of their staff. Reduced visitor numbers and disrupted supply chains for fishery products have significantly impacted the livelihoods of local communities, which may both depend on and help manage MPAs. MPA management is focusing down on core operations to maintain basic functioning. However, there is consensus that effectively managed MPAs will be more resilient and that a sustainable managed ocean, encompassing MPA networks of adequate size, will be an essential component of economic recovery.

Challenges

Developing a comprehensive marine spatial plan needs patience and persistence, and can take up to 10 years. It takes time to gather information and to discuss with all involved any implications that MSP may have on livelihoods. Once the plan is agreed, further time is needed to finalise the details and obtain government approval and for implementation. For the SMSP, the Milestones created steps along the way to the 30 per cent goal and allowed time for development of the supporting spatial database and science, documents for discussions with stakeholders and the independent assessments and analyses that informed the iterative process with stakeholders and civil society.

It is also a challenge to ensure that all sectors participate fully and that equity issues in relation to engagement and contribution are appropriately addressed. The fact that the SMSP stakeholder engagement process and governance framework were designed from the start to ensure participation from all sectors was helpful. It is important to have a government champion for an MSP and consistency in the core team to build trust with stakeholder groups.

The future may hold greater challenges, in terms of implementing the SMSP, integrating and coordinating regulatory authorities for many different uses and activities in the zones, and encouraging stakeholders to comply with the new legislation once enacted. Given the immense size of the area covered by the new MPAs, this will require additional resources. Several options are being considered, including an independent authority; discussions are on-going and will be finalised in 20202021. For monitoring and surveillance, a combination of approaches will likely be adopted, involving existing authorities (e.g. Coast Guard) and making use of the rapidly evolving global monitoring and surveillance technology to strengthen the existing system.

Key lessons learnt

- Political support and commitment to the process from the beginning, with leaders, including the president, understanding the purpose and objectives of the initiative, represented a major factor in success. Project staff reported back regularly to Cabinet and sought feedback from decision-makers, developing the political will that was needed to follow the six-year process.

- Establishment of the right partnership at the beginning was essential: as a small island developing state, Seychelles lacked prior MSP experience, technical capacity and knowledge for the MSP process. TNC provided MSP expertise, a process and science lead and a project manager. The project manager is based in Seychelles and able to talk regularly to the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change.

- Trust-building was critical. Given the lead role of the Ministry, there were concerns among some stakeholders that biodiversity protection would dominate discussions. It was continually emphasised that the SMSP was multi-objective, and that it was a government priority to ensure both biodiversity conservation and sustainable livelihoods.

- Spatial data are vital for an MSP. To ensure that sectors were equally well informed and proposals were evidence-based, relevant scientific data and local knowledge were made available from the start. Each sector provided spatial information indicating its priority areas, and also reviewed data from consultations to ground truth them for accuracy. The GIS (geographic information system) methodology must also be able to receive confidential or proprietary data and use it to develop proposals without revealing specific locations.

- Given that sectors often differ in their level of understanding of the issues and have different capacities for participation, project staff made sure that committee meetings and reporting arrangements suited all involved. Technical Working Groups were established for specific sectors and topics (e.g. fisheries, tourism, finance, climate change) allowing space for technical discussions and developing draft products.

- Time is needed for stakeholders to gather the information to present their arguments, and for discussions with them of proposals as these arise. It was accepted that the process would slow down if lack of agreement or misunderstandings arose, and facilitation focused on gathering information to help resolve issues and obtain a high level of support.

- A consistent effort was made to ensure key stakeholders were present during relevant discussions so that many views could be presented and decisions were transparent. Meeting materials were distributed and comments received to ensure all views were incorporated. Public information sessions were held on all the main islands to also reach civil society and stakeholders. Finalised meeting minutes and other documents were made available through the website.

- The issues of new protected areas and future exclusion of industrial tuna fishing, oil and gas exploration, and marine charters for sport fishing were difficult, and impartial facilitation (independent from the Ministry) ensured that all sectors were able to discuss the proposed locations and potential impacts. An economic assessment for industrial tuna fishing was very useful and, during the zoning process, all sectors agreed to forego some areas that they had mapped as “high value”; ultimately, a compromise was reached between economic development and protection of key areas for biodiversity and ecosystem function.

- It is essential to understand that the adage “one size fits all” does not apply to MSP. Nevertheless, in the same way that lessons learnt about MSP from other geographies were used to develop the Seychelles process, lessons from the Seychelles MSP will apply elsewhere.

Project contacts

Those involved in the SMSP would be pleased to share the Seychelles experience and lessons learnt.

Joanna Smith, Seychelles MSP Process and Science Lead | E-Mail

Helena Sims, Project Manager, SMSP Initiative | E-Mail

Alain de Comarmond, Principal Secretary, Seychelles Environment Department | E-Mail

Endnotes

- Laurence, D. (2020) “Seychelles Protects 30 Percent of Territorial Waters, Meeting Target 10 Years Ahead of Schedule”. Seychelles News Agency, 26 March.

- https://oceanconference.un.org/commitments/?id=19023

- https://seymsp.com/the-initiative/

- http://msp.ioc-unesco.org/msp-guides/msp-step-by-stepapproach/

- http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au

- http://mappocean.org

- http://msp.ioc-unesco.org/world-applications/americas/stkitts-nevis/

- “The State recognises the right of every person to live in and enjoy a clean, healthy and ecologically balanced environment and with a view to ensuring the effective realisation of this right the State undertakes to ensure a sustainable socio-economic development of Seychelles by a judicious use and management of the resources of Seychelles.”

- http://www.egov.sc/edoc/pubs/frmpubdetail.aspx?pubId=26

- https://seychellesresearchjournal.com/archives/archive-1-2/

- IUCN/WCPA (2008) Establishing Marine Protected Area Networks-Making It Happen. Washington, DC: IUCN WCPA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and The Nature Conservancy.

- Day, J., Dudley, N., Hockings, M., Holmes, G. et al. (2012) Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas. Gland: IUCN.

- Klaus, R. (2015), Strengthening Seychelles’ protected area system through NGO management modalities, GOS-UNDPGEF project, Final report.

- See separate case study prepared for the Commonwealth Blue Charter Blue Economy AG.

- https://seymsp.com/outputs/

Download this case study (PDF)

View all Case Studies

Media contact

- Josephine Latu-Sanft Senior Communications Officer, Communications Division, Commonwealth Secretariat

- +44 20 7747 6476 | E-mail